Glencairn Museum News | Number 2, 2017

Powwowing in Pennsylvania: Healing Rituals of the Dutch Country exhibition in Glencairn's Upper Hall.

The full text of the exhibition catalog for Powwowing in Pennsylvania: Healing Rituals of the Dutch Country follows below (or click here to download the pdf). The catalog essay is titled, “The Heavens are My Cap and the Earth is My Shoes: The Religious Origins of Powwowing and the Ritual Traditions of the Pennsylvania Dutch.” In addition, a full-color printed version of the catalog may be purchased for ten dollars at either Glencairn Museum or the Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University.

Religious orders across the globe, transcending lines of creed and ethnicity, engage in ritual as an active part of spirituality in practice, prayer, worship, and gathering. While the particular aesthetics and functions of ritual process are often unique to each faith experience, the use of ritual is also a unifying element in human experience, serving as an effective means to create and define meaningful interactions, spaces, and outcomes.

Ritual is by no means unique to the religious setting, as ritual practices interpenetrate all fields and levels of society, shaping and integrating the domestic, political, occupational, agricultural, and countless other social realms into a coherent whole. At the very same time that ritual is universal and ubiquitous, the performance of ritual within a specific context can serve to both delineate and reinforce a distinct sense of ethnic, cultural, national, or religious identity, revealing and emphasizing as many differences and divisions within humanity as there are similarities. Rituals can therefore serve to both divide and unify, to dissolve and to reconcile, to harm and to heal.

Pennsylvania’s tradition of ritual healing known as powwow, or Braucherei in the language of the Pennsylvania Dutch, is one of many vernacular healing systems in North America that combines elements of religion and belief with health and healing.1 Informed primarily by oral tradition, powwow encompasses a wide spectrum of healing rituals for restoring health and preventing illness, among humans and livestock. Combining a diverse assortment of verbal benedictions, prayers, gestures, and the use of everyday objects, as well as celestial and calendar observances, these rituals are used not only for healing of the body, but also for protection from physical and spiritual harm, assistance in times of need, and ensuring good outcomes in everyday affairs. The majority of these rituals are overlain with Christian symbols in their pattern and content, comprising a veritable wellspring of folk-religious expression that is at once symbolic, poetic, and imbued with meaning worthy of serious attention and exploration.

Figure 1: Powwow Chair, Late 19th century, Manheim, Lancaster Co. Thomas R. Brendle Museum Historic Schaefferstown.

A chair used specifically for powwowing, upon which patients were seated. Although appearing to be a normal chair in all respects, the following symbolism is attributed to it: The red paint symbolized the blood of Christ; the two arches in the cresting rail—the two tablets of the law given to Moses; the two large vertical stiles—the pillars of the church; the three vertical spindles—the apostle Paul, Jesus and Peter, the Rock; the front lower stretcher—the Judas the betrayer (upon which the patient should rest her right foot in disdain); the three rings on the legs—the Holy Trinity; and the low construction of the chair was to humble the patient to receive healing.

In this traditional world view, warts can be cured with a potato and an invocation to the Holy Trinity by the light of the waxing moon. Verses of scripture are employed to stop bleeding from serious injuries. Burns are treated by blowing three times between cycles of religious invocations to dispel the heat from the body. A smooth stone from the barnyard can heal illnesses that prevent draft horses from working, and written inscriptions are fed to cattle to prevent parasites. The proper placement of a broom by the front door will protect from malicious people and spirits, and a pinch of dust from the four corners of the house when stirred into coffee will prevent homesickness. Farm and garden tools greased with the fat from frying Fasnacht cakes will ensure a prosperous growing season, and the ash from the woodstove sprinkled over the livestock on Ash Wednesday will prevent lice. Wild salad greens eaten on Maundy Thursday prevent illness and ensure vitality. Eggs laid on Good Friday are concealed in the attic for protection of the house and farm, and are especially good for removal of illness.2

All of these ritual procedures are classic expressions of the powwow tradition once commonly practiced in Pennsylvania Dutch communities. These examples can either challenge or appeal to our notions of what is considered acceptable behavior for religious people, presenting a wide range of experiences that may overlap at times with formally-accepted, officially-sanctioned religious practice and those elements that may be relegated to a vernacular, or folk expression of religion.3 Although these practices tend to be concentrated in the core region of southeastern Pennsylvania, they are not limited to the state, or even North America, and have been found in many places where the influence of the Germanic diaspora has spread, including Southern Appalachia, the Ozarks, the Midwest, the Dakotas, Ontario, and even Brazil and Russia.4

As part of a spectrum of traditional health belief systems in the United States, Powwowing within the Pennsylvania Dutch community is comparable to other folk-cultural and ethnic healing practices in North America, such as Benedicaria or “Passing” among Italian-Americans, Root-Work in the deep South, Santeria of the Caribbean and southern United States, curanderismo in the Southwest, “granny doctors” in southern Appalachia, and the healing traditions of the Cajun traiteur, all of which blend ritual, faith, and healing.5 Despite obvious contrast with modern biomedical healthcare, these traditional healing systems are used in the present day as alternative and complementary medical practices that are blended with conventional care for the benefit of those who wish to engage a healing system that is sympathetic to religious and cultural values.6 Powwow rituals provide the rare opportunity to examine the diversity of religious ritual in a healing context, and expand our awareness of the interrelation between official and folk-religious patterns.

Although methods and procedures have varied considerably over three centuries of ritual practice within the Pennsylvania Dutch cultural region, the outcomes and experiences surrounding this tradition have woven a rich tapestry of cultural narratives that highlight the integration of ritual into all aspects of life, as well as provide insight into the challenges, conflicts, growth, and development of a distinct Pennsylvania Dutch folk culture.

Figure 2: Removing warts by the light of the waxing moon with a potato is one of the most common powwow experiences in southeastern Pennsylvania. Courtesy of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Of Warts and Waning

Of all the powwow rituals that have been practiced in Pennsylvania up to the present day to restore health and healing, the most common of these are for the removal of warts. Ranging from trifling annoyance to painful excrescence, a wart is one of the most stubborn conditions encountered by the majority of people at least once over the course of a lifetime. Modern conventional medicine can also struggle to permanently prevent the return of warts, even after repeated treatments, some of which are painful or invasive to the patient. The non-invasive rituals used to treat warts among the Pennsylvania Dutch are some of the least complicated of all powwowing procedures in structure. These rituals combine poetic blessings, the use of a common everyday object such as a potato or a penny, and are scheduled according to the phase of the moon. Despite their simplicity, these rituals are perhaps some of the most integrated into aspects of everyday life, with far-reaching implications that overlap domestic, agricultural, and cosmic beliefs. This integration, coupled with a sense of universal accessibility—literally anyone can do it—has ensured the survival of these processes into the present day, despite substantial contrast with conventional biomedicine.

As a child, my first exposure to these beliefs was through my grandmother, who explained to me that her grandfather had powwowed away a tenacious wart on her hand when she was a young girl, using nothing more than a potato. His procedure was simple, and she recalled that under the witness of the full moon, he cut the potato in half, and rubbed each half on the wart. Then he put the halves back together and buried them beneath the downspout under the eaves of the farmhouse. All the while, he quietly spoke words in Pennsylvania Dutch, a language that my grandmother had never been taught. Within a short while, the wart was completely gone.

It may come as a surprise to many that there is nothing particularly unusual about this experience among older Pennsylvanians. Although puzzling to an outsider, these types of common ritual involvements were neither scrutinized nor questioned to any great degree. It was not bothersome to my grandmother that she did not understand the words spoken by my great-great-grandfather, because the cure was understood to have been effective. Furthermore, she implicitly understood that as the potato rotted away, so did the wart.

Although the wart-cure is one of the simplest ritual applications of powwowing, the basis for how it is perceived to work is far more complex than appearances would suggest. In fact, this wart-cure provides a glimpse into a system of belief that expresses and embraces a whole worldview.

The phase and visibility of the moon are believed to be crucial for this process, as a beacon of cosmic order, and an agent of change, growth, and dispersal. Echoing principles delineated in the ever-present agricultural almanac, the moon, as it waxed to full, was believed to exert a particular force away from the earth, powerful enough to enhance the growth of ascending plants, such as corn or beans, as well as affect the rise of the tides, or the wetness and quality of wood when cutting timber, or even promote the growth of one’s fingernails and hair. It is no wonder then that this lunar force was believed to assist in the transference of illness to the potato, which, when cut in half, has a cross-sectional profile that resembles the round, white, textured surface of the full moon.

However, close examination of the farmer’s almanac would suggest that a proper potato crop was to be planted, not in the waxing moon, but when the moon is on the wane. This is when the moon’s force was directed towards the earth, enhancing the downward growth of roots below the soil. By working against this commonly held principle and interring the potato in the waxing moon to cure a wart, it was believed that the potato would be more likely to rot away under the dampness of the downspout or below the drip-line of the eaves. This location represented the outermost boundary between the home and the outside world, separating that which is familiar from the unknown—a perfect, liminal place for the illness to be relegated until it is defused.

Although most recipients of ritual healing rarely hear the words that accompany these processes, as such blessings are often spoken sotto voce, these expressions are often descriptive of the ritual’s mechanics and the desired outcome. The “moon prayer” that typically accompanies this wart remedy has been preserved in both oral tradition and written sources. One transcription, recorded in a doctor’s ledger from 1830 in the Oley Valley, reads: Alles was ich sehe das wachse, und was ich fühle das vergehe im Namen des Patri, Fillii et Spiritu Sancti (All that I see may it increase, and what I touch, may it vanish, in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit). Other sources use the Pennsylvania Dutch words zunemme (to wax, increase) and abnemme (to wane, decrease), relating the withering of the wart with the waxing of the moon in an inverse relationship that reflects the direction of the moon’s force of influence. The word zunemme also has a double-meaning: both “to wax” and “to take on”—as the moon itself is thought by some to actually take on the wart.7

Verbal elements of powwow ritual, consisting of blessings and religious benedictions, are part of a memorized system of oral tradition, typically taught by a woman to a man, or vice versa. The rich imagery contained within these prayers, derived from scriptural and legendary narratives, is expressed in poetic rounds that are often metered and rhymed as part of their mnemonic function.

I learned a different variation of this moon-prayer from a traditional powwower in Berks County just over a decade ago, and since that time I have had many opportunities to use it for friends, relatives, and neighbors. It is one of many aspects of the tradition that was taught to me by word of mouth that I was instructed to never write down, and to only teach it to those who would wish to learn. I deeply respect these admonitions, and will not be committing any specific aspects of my experiences with the oral tradition to print. These words are in one sense like a precious heirloom—a sentiment that I’ve heard from many who learned these traditions from older family members. In a very real sense, at the same time, these prayers are part of a living tradition, and should not be regarded as a mere relic of the past.

Just like prayers belonging to officially sanctioned religious activities, powwow prayers and blessings incorporate invocations and supplications to divine forces and saints. However, the objectives in powwow rituals tend to be broader in scope, closely resembling prayers attributed to the comprehensive system of medieval prayers to the saints, used for concerns as varied as safe passage in a storm or finding an object that is lost. While all prayers are in a basic sense a form of communication and negotiation with divine forces, powwow blessings also serve as the script for a distinctive form of cultural and ceremonial performance, engaging both the patient and practitioner in a ritual context composed of elements that are at once mundane, cosmological, and sacred. Central to many of these ritual performances is the use of everyday objects. Such materials are incorporated into ritual in a manner that contrasts with ordinary use, but echoes the role that the object plays within a larger context—supporting the notion that an object imparts some measure of the sacredness of life.

Other forms of the lunar wart-cure involve the use of chicken feet,8 an onion, or a bone as the vector of illness removal.9 In the last case, the bone is certainly not expected to rot away, like the potato, the feet, or the onion, but instead it is to be plucked from where it may lie in the barnyard, rubbed over the afflicted part, and then returned to the exact spot of ground from which it was taken. Similar acts of selecting, using, and replacing a stone are used for other disorders, such as sweeny (a form of muscular atrophy) or persistent nose-bleeds.10

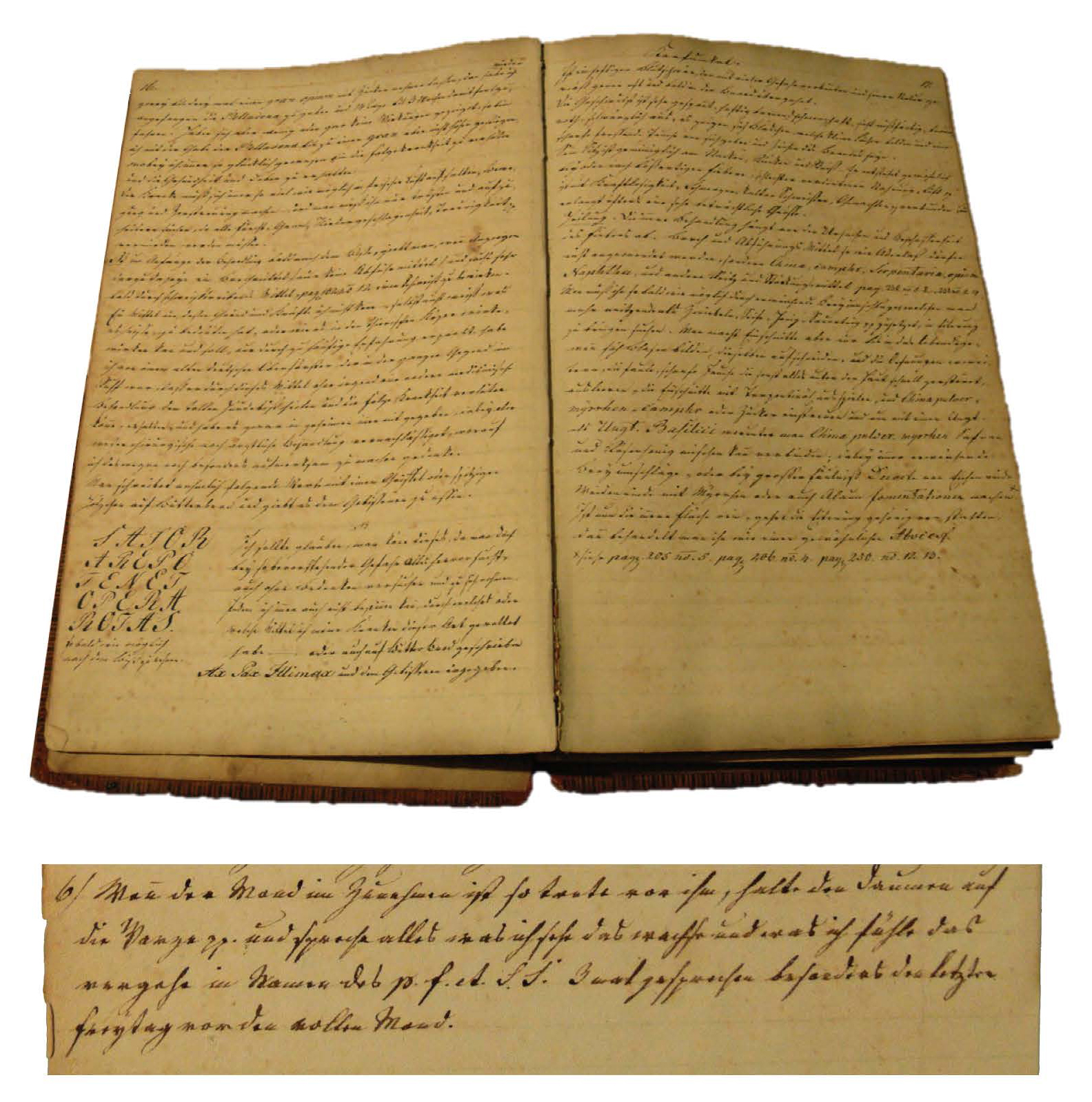

Figure 3: Doctor’s Manual, ca. 1830, Oley Valley, Berks County—Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

An early 19th-century manuscript doctor’s manual, separated into chapters for materia medica, illnesses and symptoms, terminology in German and Latin, as well as several entries of Sympathie or sympathetic cures. Includes incantations to remove warts using the moon, stopping blood, soothing burns and other common cures. Includes the rare usage of Latin for the Trinitarian invocation, “In Nomine Patris, et Fillii, et Spiritu Sancti,”—In the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—indicating a Roman Catholic influence in the creation of this work.

Also includes the SATOR square palindrome inscription, and instructions to write it on butter bread, and to eat it as a cure for rabies.

Another type of wart-cure ritual involves the use of a penny to rub the wart, which when spent or abandoned at a crossroads, would transfer the wart to the next person who possessed it. In these cases, while the moon still plays a central role in the transference, the accompanying words are quite different. A man from the Kutztown area once told me that “the butcher bought my wart for a penny.” This pronouncement echoes the Pennsylvania Dutch phrase used in such cases, Ich kaaf dei Waartz fer ee Sent—“I’m buying your wart for a penny.”

Still other accounts suggest rituals involving the counting of the warts as a cure,11 echoing the old belief that warts could be contracted by pointing at the stars and counting them.12 This act, though seemingly harmless enough, and certainly not worthy of divine punishment by modern standards, can be contextualized in light of Biblical passages where counting the stars is a power ascribed to God alone (Psalm 147:4). Even in the passage in Genesis where Abraham’s descendants are compared to the stars, the suggestion is that quantifying the infinite is beyond human abilities: “Look now toward heaven, and tell the stars, if thou be able to number them” (15:5).

Despite the fact that some folk-religious traditions, such as powwow, may resonate with patterns, sights, and sounds ascribed to earlier periods of a culture’s or religion’s development,13 it is equally true that official expressions of faith are entitled to the very same privilege. But again, neither vernacular nor formal religion should be regarded as mere vestiges of the ancient, and instead, parts of a dynamic continuum of active relationships, informed by the past and working in the present.

Learning to Powwow

The original word in Pennsylvania Dutch for these ritual practices is Braucherei, which literally from its German linguistic origin describes an accumulation of customs, ceremonies, traditions, and rites derived from brauche (to use, to need, to administer or employ), as well as Breiche (customs, ways, traditions) and Gebrauch (ceremony, custom, or ritual).14 A female practitioner of Braucherei is called a Braucherin and a Braucher if male. In the present day, as the use of Pennsylvania Dutch has declined in the core region of the Dutch Country, a practitioner is also called a “powwow doctor” or “powwower.”

In some parts of the United States, a powwower is also called a “hex-doctor,” which implies the healing of illnesses believed to be caused, either unintentionally by a grudge, or deliberately by a curse, commonly known as a hex in both English and Pennsylvania Dutch. Any maliciously-intended ritual activity that is used to harm an individual or livestock is called Hexerei (literally, malicious witchcraft).15 Like the word hex-doctor, use of the term Hexerei can also be ambiguous, and in some areas of North America it is synonymous with the word powwow; however, in Pennsylvania Dutch this word always has a negative connotation. The powwower’s role is not only to ritually cure unintentionally-occurring illness, but also to counteract the results of any malicious use of ritual that would produce a hex.

Despite the variety of nuanced terminology for ritual practitioners, not everyone who powwows would identify him or herself as a practitioner, which inherently implies specialization or vocation on some level. Years ago, when powwow was more common than it is today, a member of the family might powwow for anyone in the Freindschaft (an extended notion of the family, including friends and neighbors), and still not claim to be a practitioner. There are those who specialize in powwow as an occupation, but such a thing tends to be controversial, as payment is usually neither specified nor required. Although historically there have been powwow practitioners with highly lucrative practices, this is not common in the present day.16

Both of my paternal great-grandmothers could powwow, but neither would have considered herself to be a powwower in any formal sense of the word. Instead, both were familiar with common ritual cures that would have been known by many housewives of their generation. One of my great-grandmothers taught me a cure for hiccups when I was a child. The other lived on Hill Street in Lebanon, Pennsylvania, just a few houses down from a well-known powwower of the professional variety by the name of Reppert. In the 1930s and 40s, cars and horse-drawn buggies would line the street on a Sunday afternoon, when patients would come to see him. My great-grandmother would help out when the patients were too numerous, and she would powwow for those requesting assistance with childhood ailments, especially for “livergrown” children.

Livergrown is the English word for the Pennsylvania Dutch notion of being Aagewaxe,17 a condition once widely known across many early communities in America18 and called by a variety of names, such as “hidebound” or “gripes.” This disorder is one of many culturally-defined illnesses that do not readily fit the language of modern biomedicine. Equated with infant colic, this disorder is characterized by abdominal pains and cramps. The belief was that these sensations were caused by the liver attaching itself to the inside of the body cavity, thus the word Aagewaxe implies that which has “grown attached.”

My great-grandmother powwowed for livergrown with a common process involving the use of oil, which was applied to the child’s sides with her thumbs. She would recite a prayer while employing a form of light massage. Although no one in my family remembers the prayer, there are two commonly recorded prayers for this process. The first is spoken in the dialect: “Aagewaxe, geh weck vun meim Kind sei Ripp, yuscht wie der Grischdus aus sei Gripp gange iss” (Livergown, depart from my child’s rib, just as Christ got out of his crib).19 Another prayer is derived from the standard German Luke 18:16: “Und Jesus sprach, Lass die Kindlein zu mir kommen, und er segnete sie zu der selbigen Stunde. . .” (And Jesus said, let the little children come unto me, and he blessed them at that very hour. . .).20

Figure 4: Left: A powwower’s cane, also called a “throw-stick,” used as a wand for healing and divination, Montgomery County, PA. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer. Middle: A cane wrapped with four carved serpents, used by a powwower from Hamburg, Berks County. Courtesy of the Mercer Museum, Doylestown, Pennsylvania. Right: A naturally formed spiral cane from vine, used as a powwow cane in Berks County. Courtesy of the Mercer Museum, Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

Customarily, powwowing is learned by word of mouth, as part of an oral tradition that is memorized, consisting of prayers, gestures, and ritual procedures. Some rituals are for specific illnesses, while others are part of a more comprehensive approach to bless and bring balance to the whole human body. The oral tradition comprises perhaps the single-most comprehensive cultural repository for ritual experience, and yet is guarded by protocol which determines the manner and frequency of how that information can be transmitted. There tends to be a strong admonition against putting such memorized content into written form, except for personal reference.

With very few exceptions, this protocol requires a male to learn from a female practitioner, or vice-versa (and usually the bulk of this oral material is in Pennsylvania Dutch). Although it is unknown how this alternating gender requirement developed, it certainly has contributed to a strong sense of gender equality in the tradition. Female practitioners are as common and known to be as effective as male practitioners, although occasionally there is some specialization among women for women’s health issues. This gender requirement also excludes anyone from the practice with a tendency toward sexism—which would certainly be an obstacle to healing. When this tradition is passed down in families, it often skips a generation as it alternates. A grandmother might teach her grandson or a granddaughter may learn from her grandfather.

Rarely, when the tradition is held closely within a family, an exception to this gender-specific teaching can occur. Younger generations can sometimes gain firsthand experience by watching another family member powwow, without regard to gender. Sadly, it is much more common today to hear of such practices disappearing when a practitioner cannot find a willing pupil of the appropriate gender. As the language gap widens in southeastern Pennsylvania, and older generations of native speakers of Pennsylvania Dutch are passing away, and few younger people are learning the language, the tradition has had to adapt in order to survive.

In keeping with this traditional format, powwow is typically taught only under the condition that it be learned by a person who intends to earnestly use it to help other people, and not for the purpose of personal edification, curiosity, or intellectual and academic interest, especially if this were to lead to public scrutiny or publication of sensitive materials. Even such noble causes as historic or cultural preservation can be highly controversial if performed in a way that compromises a culture’s values, and such efforts must be done with the utmost respect and ethical considerations.21 As with any traditional practice, powwow cannot be separated from the communities that it sustains, and therefore any efforts to engage or encounter this tradition as an outsider should begin by establishing meaningful connections with the community.

A Confluence of Cultures

While simultaneously affirming and challenging the values of present-day Americans, the religious origins of Pennsylvania’s ritual tradition of powwowing are a direct result of the blossoming of the transatlantic religious exchange of 18th-century immigration prior to the American Revolution. German-speaking Protestants and Pietists, consisting of Lutheran and Reformed church members, Moravians, as well as the highly persecuted sects of Anabaptists, such as the Mennonites, Brethren, and Amish, and a very small minority of Roman Catholics crossed the Atlantic in a mass exodus, and escaped the turmoil and destruction following the Thirty Years War and Louis XIV’s destruction of the Rhine. Pennsylvania’s English Proprietor William Penn’s open-door policies of religious tolerance provided an ideal destination not only for his own community of Quakers, but also to this religiously diverse group of German-speaking refugees from the German regions of the Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg, as well as Alsace, Switzerland, and throughout the Rhine River Valley. Each of these religious communities migrated from central Europe and adapted to the cultural climate of North America to form New World identities.

As the most ethnically and religiously diverse of the original thirteen colonies, Pennsylvania provided the fertile soil for ritual traditions to flourish in the New World. Deeply rooted in the Roman Catholic consensus of the Middle Ages, revitalized by the post-Reformation mystical elements of Pietism among the Protestant population, the folk-religious climate of Pennsylvania was the new-world point of origin for a comprehensive system of beliefs that encompassed domestic, agricultural, and spiritual life. Braucherei in its original connotation implied customs, ceremonies, rites, and rituals that served to integrate these aspects of life into a coherent narrative.

Although the ritual practices of Braucherei are undoubtedly European in origin, the notion of powwowing—as the practice is known today—proceeds from a confluence of vastly different North American cultural forces. The term was appropriated from the Algonquian languages and incorporated into English by Puritan missionaries in 17th-century New England. In its original usage, the word powwaw among the Narragansett designated a medicine man, derived from a verb describing dreaming or divination for healing purposes.22 Among the Puritans, this word took on a pejorative, and even sinister connotation, as the traditional medicine men and women were seen as obstacles to efforts to convert the native population in New England. Furthermore, because of this clash of cultures, the “powwaw” was equated with demonic practices by the English, and such stories were even included in mission correspondence by Matthew Mayhew and John Elliot to Lord Protector of the Commonwealth, Oliver Cromwell.23

Based on this use of the word in early America, the term became synonymous with “magical rituals” in a derogatory sense and the Native American word was applied by early English-speaking Pennsylvanians not only to describe the ritual practices of the Pennsylvania Dutch out of some apparent similarity in the process of ritual healing, but also to indicate a sense of judgment about the perceived “otherness” of these practices. Furthering this notion of scorn, the connotation of noise was associated with such ritual practices,24 designating the non-English Native American and Pennsylvania Dutch languages as being unintelligible or meaningless.

Figure 5: The practice of “plugging” illness into trees is well-documented among many cultures—Pennsylvania Dutch, Lenape, and English. Early accounts provide details of this procedure, and evidence of “plugged” trees was still found in the 20th century.

Left: Manuscript Directions for Transfering Illness Into a Tree, ca. 1860-1880

Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

These manuscript instructions provide a process for ritually transferring an illness into a tree: “Take a goose quill and cut it of[f] where it begins to be hollow, then scrape off a little from each nail of the hands and feets put it into the quill & stop it up after bore a hole towards the rise of the sun into a tree that bears no fruit put the quill with the scraping of the nails into the hole and with three strokes close up the Hole with a bung maid of pine wood. It must be done on the first Friday in new moon in the morning.”

The timing of this ritual was crucial, for the new moon was believed to exert a force down and inward, driving the illness into the tree; it was believed that the movement of the sun westward would reinforce the same movement of the illness into the tree. Friday was considered a beneficial day to begin such an undertaking because of its association with the crucifixion of Christ on Good Friday, and the initiation of the salvation and healing of the world in Christian tradition.

Middle: Plugged Oak Tree Remnant, Mid-19th century, [Schaefferstown, Lebanon County]

Thomas R. Brendle Museum, Historic Schaefferstown.

Discovered by a farmer chopping wood on a farm between Reistville and Schaefferstown, Lebanon County. According to local interpretation, the tree was believed to have been close to a century old when the peg and ritual deposit was placed for transferring illness into the tree, over a century prior to having been cut down. One hundred twenty annual growth rings were counted from the bark to the peg.

Right: “Baum-Segen” Broadside Prayer and Tree Plugging Instructions, ca. 1790-1810

Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

“Who trusts in God, and believes in the blessing of Jacob and in Jesus Christ, will have the power to overcome the Devil, wild animals, and danger. Put it into a hole in a tree, and urinate into it, and hammer a plug thereafter. Tree, God bless me.” This broadside also has cryptic inscriptions that follow, which appear to be written in cypher.

One of the earliest recorded uses of this word in the Pennsylvania Dutch context appears in the memoirs of Pomeranian immigrant George Whitehead, who composed his transatlantic autobiography for posterity in English in Berks County, Pennsylvania in 1795. He recollects an experience from his early life as a servant in Pomerania, when a local hangman performed a ritual to cure him of the bite of a dog believed to have rabies. In keeping with his English presentation of the narrative, Whitehead describes his skeptical master’s negative reaction to “powouring.”25 Despite its obvious anachronism on the lips of a European, this citation indicates an already well-established Americanism just before the turn of the 19th century and confirms a sense of ambivalence in connotation—both as a widely accepted term for ritual healing, but also one that may come with a sense of judgment.

Figure 6: A fold-out print from the Sixth and Seventh Books of Moses, with Latin, Hebrew and German inscriptions. This work was alleged to be the extra-biblical writings of the ancient Hebrews and Christian Cabalists, but was first compiled from manuscript sources in the 1840s by German publisher Johann Scheibel, and sold as part of a series on ceremonial magic. Shortly thereafter it became one of the most widely circulated works to inspire folk ritual practice on both sides of the Atlantic. The work has a sinister connotation in Pennsylvania, however, as it includes instructions for casting the seven plagues that Moses visited upon Egypt, as well as instructions for spirit conjuration. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Powwow is the most common term for the tradition in the present day, and as the everyday use of Pennsylvania Dutch has declined, awareness of the origin of the word powwow is also limited. It is a common perception, despite copious evidence to the contrary, that the practice was derived from contact with Native Americans. Others, perhaps confused about the origins of the word powwow, have suggested that the tradition was based upon, or at least enhanced by, a desire to imitate or “play Indian,” as a way for Americans of European descent to explore the exotic stereotypes of the indigenous experience.26 Both of these perceptions of the practice are perhaps the result of a limited understanding, not only of the role and development of powwow as an English word in Pennsylvania, but also of the range of folk-religious experience in the United States—so much so that these types of non-sanctioned ritual practices are perceived to be out of place or exotic when practiced by Americans of European stock. These ritual practices are so frequently omitted and rarely discussed as part of the well-accepted narratives of early American and European history, that one can hardly begrudge bearers of the notion that powwow must have been borrowed from someone or somewhere else.

This idea of cultural borrowing, however, is wound in and through the Braucherei experience in both a syncretic and attributive sense, as even in Europe, rituals of Germanic cultural origin were once idealized as expressions popularly believed to have proceeded from Egyptian, “Gypsy (Romani),” Roman, or Jewish sources.27 While some of these influences are confirmed (such as occasional references to the Roman author Pliny the Elder), in general this form of cultural appropriation, especially that which concerned the Jewish or Romani element, says more about the idealized perceptions of the culture doing the borrowing, rather than any accurate representation of the culture from which certain ideas may or may not have actually been borrowed.

Figure 7: An illustrated frontis of the Gypsy King of Egypt—a legendary author in Pennsylvania’s powwowing literature, bearing a frisian cap, stylus and book. Verschiedene Sympathetische und Geheime Kunst-Stücke (Various Sympathetic and Secret Formulae), ca. 1800. PA German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

In most cases extra-cultural elements serve a particular function, while indulging a sense of exoticism. Some materials attributed to the Romani people (falsely believed to have come from Egypt)28 are thought to have great ceremonial and magical power, whereas texts or sources derived from Hebrew are believed to carry with them a sense of ancient biblical authority and power.29 At the same time, objectification goes both ways, and can even become a means to condemn: some have blamed the diversity of early Pennsylvanian Christian ritual practices on the latent presence of a pagan or heathen frame of mind, and while there is a level of truth to the ancient precedents and origins of many religious practices, certainly both official and folk forms of religion maintain some measure of this ancient influence.

This ambivalence about the religious origins of Pennsylvania’s ritual traditions, and hesitancy to claim ownership in origin or practice, is not merely out of perceived exoticism, but especially the result of changes in doctrinal, theological, and institutional structures of religion, whereby change is part of an official and authoritative process, determining which aspects of religion will be endorsed, and what is to be discouraged. A general sense of “correctness” is associated with endorsement, while discouragement or prohibitive sanctioning determines what is considered “deviant,” “unorthodox,” or even “heresy.”

On the other hand, folk religion, as a parallel trend of ever-changing, non-sanctioned religious experience, has a tendency to maintain some portion of that which has been discarded by orthodox religion, especially when those discarded elements are part of a cultural, regional, or ethnic expression linked to a community identity. For this very reason, Pennsylvania Dutch culture unconsciously maintained a certain level of historical Roman Catholic elements despite its predominantly Protestant culture. Invocations to the Virgin Mary and the whole hierarchy of specific saints for the healing of precise ailments, liturgical prayers such as the Ave Maria used within the context of penance, as well as the use of objects or places considered holy or sacred—these are just some of the ritual elements proceeding directly from a Roman Catholic past that are interwoven into Pennsylvania Dutch culture.30 Although none of these elements are expressed within the corpus of officially sanctioned religious experience in the Protestant churches and adherence to these practices may at times be invisible to the clergy, the membership of the churches may express these traditions in the home or other private venues where their role and ritual function within domestic, agricultural, and healing traditions is affirmed.

Figure 8: Der Wahre Geistliche Schild, Heiliger Segen, und Geistliche Schild-Wacht (The True Spiritual Shield, The Holy Blessing, and Spiritual Shield Vigil).

Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Three editions of the classic compilation of European 16th-century benedictions, prayers, and blessings for protection from danger, evil spirits and plague. These works, while largely unknown today, were once frequently recorded in manuscript form throughout Pennsylvania and used for powwowing, as well as printed in Reading and Erie, Pennsylvania, as well as Cincinnati, Ohio. The two open, hard-backed editions were owned by Pennsylvanians.

Roman Catholic Roots of Powwow

Although the religious climate of Pennsylvania was decidedly Protestant from the onset, the early folk culture was still deeply rooted in centuries-old, pre-Reformation beliefs and observances, some of which are still maintained today.31 These attitudes and practices are often mistaken for theological or doctrinal castoffs from previous generations, rather than part of a distinctly European worldview, interwoven not only through the ages, but also throughout the total sphere of life.

During the Middle Ages, by the time that the culture of Christianity rose to ascendancy from the fall of the Roman world, Europe was already on a new religious trajectory that would serve to redefine the sacred and transform devotional practices. The development of the cult of the saints would be one of the defining factors in this transition, as the remains of the faithful departed and their devotional shrines replaced the civic centers of Roman life.32 The remains and relics of the martyrs delineated a new spiritual topography that spread across Europe, plotting the routes of the pilgrimage, determining the sites of Gothic cathedrals, and consolidating religious authority.

These ancestors of a spiritual family, saints and martyrs, served not only as holy intercessors capable of touching the lives of mortals, but also as human faces that mediated contact with a heavenly, supernal reality.33 Never before had Earth and the heavens seemed to so closely intersect. The saints were considered irrefutable evidence that the sacred could take physical form, and every physical manifestation of creation was the result of a spiritual counterpart. At the same time, the ever-growing hierarchy of the clergy merged with a heavenly order that encompassed the very choirs of heaven, the patriarchs and prophets, the Saints and Apostles, the Holy Family of Mary, Joseph and the Infant Christ, and above all, the ineffable mystery of the Holy Trinity.

However, the earth was also a realm of great peril, as the devil and the forces of darkness were given free reign to bring calamity and misfortune, illness and infirmity, pestilence and plague.34 But the sufferings of humanity were not only to be relieved in the salvation of the afterlife, but in the restoration of the natural order and healing of the flesh through contact with the sacred.35 Holy sites, objects, and people were the answer to this mortal conundrum, and served not as reminders of distant heavenly realities, but as proof of divine immanence.

Even when one’s station in life did not permit direct contact with the sacrosanct, prayers and petitions to the saints could be offered to bless and assist in all earthly affairs and heal all infirmities. Blessed inscriptions on paper and fabric as well as medals stamped with the images of the saints could be worn on one’s body to guide and protect in daily life, on journeys, and in times of war.36 A sacred calendar, reflecting the movements of the heavens as beacons of cosmic order, synchronized the days, months, and seasons with a cyclical pattern of veneration and devotion, and every transition in life was given a special liturgical rite and benediction—from birth to death.37 The health of a person extended beyond his or her physical body, to include family and neighbors, home and farmyard, barns and livestock, fields and crops, and seamlessly joined a universal order that stretched to the four corners of the earth, and was reflected in all creation.

Figure 9: Clockwise Right: European Breverl, Austrian dialect for a little protective letter, featuring the Caravaca Cross, 18th century; colored etching Glückselige Haussegen (Sacred House Blessing) with the Virigin Mary and the monograph of the Three Kings, CMB, and the Segen-Stern, a six-pointed star with the letters IEHOVA spread across the points, 19th Century, Munich; small Gnadenbild (Holy Image) of the Virgin Mary, which was physically touched to the Holy Image of the Virgin Mary in Passau, Lower Bavaria,(38) 18th century; Die heiligen sieben Himmels-Riegel (The Seven Holy Bars of Heaven), a protective prayer allegedly given to a hermit by his guardian angel, Cologne, Germany; three Fraisen-Steine (Epilepsy Stones) cast from zinc with images of the saints, carried by epileptics for deliverance from seizures; Die sieben Heiligen Schloß. (The Seven Holy Seals) a seven-fold prayer for protection, claiming to have been printed “on the German press in Jerusalem,” 19th century. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

This concept of the sacred was so integrated into all aspects of life and proved to be so incredibly stable that even when the rise of the Reformation and Renaissance would shake Europe to its very core, this cosmic arrangement persisted and colored later expressions of religious piety and everyday life by shades and degrees. Even centuries later, after changes in theology, science, fashion, and economy, prayers that appeal to the saints would continue to describe these heavenly hierarchies:

“Today I rise and tend to the day which I have received, in thy name: The first is God the Father †, the other is God the Son †, the third is God the Holy Ghost †—Protect my body and soul, my flesh and my life, which Jesus, the Son of God himself, has given to me; whereupon shall I be blessed, as the Holy Bread of Heaven that our loving Lord Jesus, the Son of God, had given to his disciples. When I go out from the house over the threshold and into the streets, Jesus † Mary † Joseph †, the Holy Three Kings, Caspar †, Melchior † and Balthasar † are my travel companions—the Heavens are my hat and the Earth is my shoes. These six holy persons accompany me and all that are in my house, and when I am on the streets, so shall they protect my journey, from thieves, murderers, and malicious people. All those who meet me must have love and value for me. Therefore help me God the Father †, God the Son †, God the Holy Ghost †, Jesus, † Mary, † Joseph, † Caspar, Melchior, Balthasar, and the Four Evangelists be with me in all my doings, trade and commerce, going and coming, be it on water or land, before fire and inferno, they will protect me with their strong hand. To God the Father †, I reveal myself—to God the Son †, I commend myself—in God the Holy Ghost †, I immerse myself. The glorious Holy Trinity be above me, Jesus, Mary and Joseph before me, Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar be behind and beside me through all time, before I come into eternal joy and bliss, help me Jesus, Mary and Joseph. Caspar † Melchior † and Balthasar †, pray for us now, and in the hour of our death. Amen.”39

This Powerful Prayer (Ein sehr kräftiges heiliges Gebet) originates in the city of Cologne, at the Cathedral dedicated to the Three Kings, but was used and published just before the turn of the 20th century in Kutztown, the heart of the Pennsylvania Dutch Country. This prayer may seem about as far removed from the rational theology and humble piety to be expected of the Lutheran and Reformed congregations as could be imagined, that is, until one compares it with other prayers associated with powwowing, where rituals may conclude with making the sign of the cross three times, followed by the Ave Maria in series with penitential recitations of the Apostles’ Creed and the Lord’s Prayer. While the latter two expressions were certainly at the core of Protestant expressions of faith, nevertheless this ritual context was wholly foreign to the offices of the Protestant churches.

Despite the implications of such Roman Catholic elements in Protestant communities, the Pennsylvania Dutch had certainly not forgotten that the celebrated image of Dr. Martin Luther graced the inside covers of not only their German Bibles, but also early Pennsylvania prayer books, and even their children’s spelling-books and grammars. The spirit of the Reformation that inspired the transatlantic migration was hardly forgotten in the New World, and Pennsylvania, founded as a colony with no state-mandated religious requirements, was a perfect place for religious expression to flourish.

It would appear that these vestigial elements of Roman Catholicism within folk culture did not merely survive in spite of Protestantism, but were fundamentally transformed and possibly invigorated by it. As the prayers to the saints and a reverence to their shrines and relics were removed from the official realm of religious expression, it was within the home that these traditions continued to grow and change into a fundamentally new creature, no longer informed by the doctrines and reinforced by the sanctioning of the official Protestant churches—but thriving nonetheless as a familial form of devotion.

Figure 10: Blessing made for Emma Jane Weidner, 1887, by Dr. Joseph H. Hageman of Reading, Pennsylvania. Hageman’s blessings were derived verbatim from European collections of folk-religious blessings, such as the Geistlicher Schild (Spiritual Shield) and the works attributed to Saint Albertus Magnus. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

The early Christian martyrs, largely forsaken by Protestant authorities, make their appearances throughout the oral and literary ritual healing traditions in Pennsylvania. Prayers for burns were used in Pennsylvania invoking St. Lawrence, martyred on an iron griddle, and prayers to St. Blaise were used for menstrual complications. St. George and St. Martin were invoked to thwart highway robbers, and St. Cyprian against curses and malicious people.40 The “Three Holy Women,” Sts. Elizabeth, Brigid, and Matilda, were invoked to cure swelling.41 The Biblical saints, patriarchs, and protagonists receive equal treatment, each with their specialized invocations: the Virgin Mary for extinguishing fire and healing burns; and St. Peter for binding and releasing thieves. The names of the four Evangelists were used to bless the body against illness and danger. The “Three Holy Men,” Shadrach, Meshach and Abednego, were invoked to cure inflammation, and their “song” in the fiery furnace was good to protect from destruction by fire, storms, infant convulsions, and the bite of a mad dog.42

These unofficial traditions served to nurture parts of the human experience that no longer had a place within public, post-enlightenment Protestant expression, especially under the careful watch of Lutheran and Reformed clergy, many of whom were educated at European universities, further dividing them from their North American parishioners. Non-ordinary experiences with spirits and the supernatural, illnesses believed to be caused by grudges or sin, even the possibility that calamity could be caused intentionally by the envy of malicious people—all of these experiences and perceptions no longer fit the Protestant climate, yet were never successfully expunged from the worldview of the people. Rituals and prayers for healing, protection, and assistance served to mitigate these concerns and integrate such narratives into a coherent and meaningful undercurrent that has served the needs of Pennsylvanians for centuries.

Figure 11: Drei-Königzettel (Three Kings Broadside), late 18th century.

Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

A European broadside of the Three Kings Prayer, which was later republished in Pennsylvania, most notably, in Kutztown by Urich & Gehring ca. 1880. This prayer developed in the wake of veneration of the Three Kings following the moving of their legendary remains to the cathedral in Cologne. The prayer appeals to the Three Kings, symbolized by the initials C†M†B† for protection against natural disaster and the predations of the wicked.

Figure 12: Drei-Königzettel (Three Kings Broadside), late 18th century. Heilman Collection.

A European broadside of the Three Kings Prayer, which was later republished in Pennsylvania, most notably, in Kutztown by Urich & Gehring ca. 1880. This prayer developed in the wake of veneration of the Three Kings following the moving of their legendary remains to the cathedral in Cologne. The prayer appeals to the Three Kings, symbolized by the initials C†M†B† for protection against natural disaster and the predations of the wicked.

Figure 13: Ein Sehr Kräftiges Gebet (A Very Powerful Prayer) ca. 1880, printed by Urich & Gehring, Kutztown

Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University—Don Yoder Collection.

A rare Kutztown broadside blessing, attributed to the Three Kings and the cathedral dedicated to them in Cologne, Germany. The concluding words in the central column ask for assurance both now and in eternity, echoing the last lines of the Roman Catholic Hail Mary,

“. . . nunc, et in hora mortis nostrae”—“Now and in the hour of our death.”

Figure 14: Right: The contents of an 18th-century European letter of blessing (Breverl) which was sealed and worn on one’s person. Left: A scapular worn around the shoulders with images of the saints, as well as an unopened Breverl, highly embellished with the beaded monogram of the Virgin Mary. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Figure 15: Blessing for Estella May Boyer, 1895 [Reading, Pennsylvania]

Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

Personal blessings for healing and protection, made by Dr. Joseph H. Hageman of Reading, Berks County. In 1911, the New York Times called him “the greatest powwow doctor who ever lived.” Hageman’s blessings were derived from a European book of blessings called Der Geistliche Schild und Heiliger Segen.

Figure 16: Early Protective Blessing, 18th century—Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

Personal protective blessing produced in black and red ink on the verso of an unidentified, 18th-century Philadelphia printed estate document. Features a winged angel with a burning heart and crown, associated with the mystical vision of the Sophia or feminine aspect of the Holy Spirit, popular among certain Pietist groups in early Pennsylvania. The angel oversees the six days of creation, depicted within the Star of David, with planetary symbols within each point and the sun in the center. However, Mars is missing, and replaced by a “J”—possibly an intentional inversion of martial influence as a protection from violence. The inscription I.N.R.I. (Iesus Nazarenus Rex Iudeorum—Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews) is a common protective inscription, flanked above and below with three crosses, symbolic of the Holy Trinity. Adonai, a Hebrew name for God meaning Lord, is inscribed on the left. Creases indicate it was folded and carried on the person.

Although the original aim of the Reformation was to fundamentally challenge the authoritative structures of Rome that mediated humanity’s connection to the divine, the resulting Protestant discourse, as both a spiritual and an intellectual movement, became increasingly centered on the use of reason and rationalism to debate rival factions, revise the tenets of faith, and expunge those elements of Roman Catholicism that had accumulated in the medieval era and were based in tradition, rather than biblical literature.43 Aside from the primary doctrinal debates concerning the nature of salvation and concerns about abuses of power, to the Protestant movement all aspects of religious experience were suddenly under scrutiny for evidence of perceived contamination from papal authority, even symbolism, iconography, and especially the role of the saints.

While the traditional Roman Catholic veneration of the saints was attacked for its extra-biblical and legendary facets, Dr. Martin Luther warned against wholesale iconoclasm in regard to the saints, advocating that those saints who were biblical in nature should be maintained for their inspirational and didactic role as models of a Christian life.44 Despite this concession, there were serious consequences of this new theology. To undermine the traditional reverence for the saints was to potentially initiate the unraveling of an entire worldview in which the supernal hierarchy of heavenly beings had the power to touch and change the lives of humans. This is not to say that Protestants dismissed a relationship with the divine, or even the angels, but holy agents with human faces were replaced with a much more remote, abstract, and cerebral conception of the divine. This transition was only partially successful.

In addition to the scriptural arguments against non-biblical saints, Protestant leaders were also distinctly aware that the destruction of the cult of the saints would dismantle the power structures that had evolved around the tombs, shrines, and relics of the martyrs and disrupt this expression of popular piety throughout Europe, as well as redefine the very nature of the sacred that originated in Roman Christianity. It was not only the folk culture that struggled with these changes; it was the very leadership of the Holy Roman Empire.

Figure 17: Latin Prayer against Witches and Demonic Attacks, 17th century, European. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer.

A rare, late 17th-century Roman Catholic protective document attributed to Fr. Bartholomaeus Rocca Palermo Inq[uisitor] of Turin. The broadsheet is printed on both sides with blessings attributed to St. Vincent, invocations of the Latin, Greek, and Hebrew highest names of God, and passages from the Gospel of John on the verso. The document was folded, sealed with wax, as well as a square metal cover.

Even the Elector of Saxony, Frederick III, The Wise, who protected Martin Luther while he penned his revolutionary vernacular translation of the Bible, was intimately connected to the cult of the saints and the power that it represented. It was well known that by the time that Luther released his German New Testament in 1522, Frederick owned over 19,000 holy relics of Christ and the saints, including one thumb of St. Anne, straw from Christ’s holy manger, a twig from the burning bush of Moses, and even a vial of milk from the Virgin Mary!45

Frederick’s relics were housed in the All Saints Cathedral in Wittenberg, where they were displayed each year on the second Sunday after Easter between 1503 and 1523, and vast sums of money were culled from pilgrims and nobles alike, who were granted indulgences for public veneration of the relics. These indulgences were part of an elaborate system designed to provide exemption in the afterlife from time spent in Purgatory prior to entry into Heaven. Ironically Frederick III put an end to his collecting following the 1517 controversy of Luther’s Ninety-Five Theses on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences, and following Frederick’s death less than a decade later, the relics were dispersed and destroyed in the wake of the iconoclastic fervor that swept across the German territories.46

But while overt display of images of the saints became forbidden in Protestant lands, poetic, prayerful invocations of the saints remained written in the hearts and minds of Protestant people, who eventually made their way to the New World.

Martin Luther & Ritual among the Protestant Clergy

As the central figure in the Reformation, Luther is often assumed to have been the living embodiment of Protestant doctrine and therefore to have been the primary proponent of the rational theology that so characterized the shift from the Roman Catholic consensus of his era. While the theology of Lutheranism certainly bears the mark of its originator, Luther himself held a much more complex view of the relation of humanity to the divine than is often reflected in the Augsburg Confession. As a mystic, Luther’s worldview shaped some of the very attitudes that would later come under criticism in Protestant theology.47 Discussions of spirits and the supernatural causes of natural phenomena were some of the highlights of Luther’s Table Talks, a publication of informal discussions held between Luther and his closest friends and colleagues.48 While these documents were never intended as the basis for church doctrine, they are revealing of the attitudes and beliefs commonly held in Luther’s time.

Luther was unshakably certain, for instance, that the devil and his demonic servants were active agents of destruction in the world, causing calamity, storms, and illnesses—and he considered himself to be a primary target. Not only did he believe that his physical illnesses were the result of continual spiritual struggles with the forces of darkness, he also asserted that doctors were of no avail in such circumstances. Luther also reinforced the old Roman Catholic notion that illness could be the direct result of sin. Although Luther admitted that scientific medicine and the aid of devout physicians were gifts from God, he maintained that clergy were more effective as healers of spiritual illness.

On the other hand, Luther also spoke of folk cures, and expounded the belief that three toads when skewered and left to dry in the sun can draw the poison out of tumors. Luther even described certain remedies that are effective only when applied by nobles, such as holy water applied by the Elector of Saxony, Frederick III. Luther also believed strongly that religiously-rebellious humans could harm their neighbors through malicious ritual means. He describes certain people (usually women) who could by infernal powers cause milk, butter, and eggs to spoil so that such food would drop to the floor when one tried to eat it, and that anyone who chastised such people for their deeds would fall victim to the plagues of the devil. Luther described that even his own mother struggled with a neighbor who was known to curse infants so that they would cry themselves to death, and cursed a clergyman with a deadly illness that no remedy could cure using the dust from his footprints. When asked about the proper recourse for such behavior, Luther cited scripture, and reminded his colleagues that in the Old Law, the priests cast the first stone at such malefactors.49

It is important to maintain Luther’s words within the proper context, and not to elevate these informally documented sessions with the reformer as articles of faith. At the same time it is also significant to note the extent to which these attitudes can also be reflected in later generations of clergy in Europe and the New World, and the way in which pastoral care included an awareness of the spiritual and physical experience of suffering. Ministry needed to answer these concerns if it were to be effective in communities where such beliefs are held in common. In some cases, Pennsylvania clergy not only answered such concerns with official forms of pastoral care, but also occasionally participated directly in powwow practices.

The esteemed Lutheran circuit-rider Rev. Georg P. Mennig (1773-1851) served and assisted in founding congregations over the Blue Mountain in Schuylkill County—but he also ministered to his community as a powwow practitioner.50 This celebrated and prolific pastor, whose tombstone boasts that “he preached 1633 sermons, confirmed 1733 and baptized 1631 people” also commissioned the printing of broadsides of powwow ritual procedures, most notably a cure for “wildfire” or erysipelas.

Erysipelas is an acute bacterial infection of the skin characterized by extreme inflammation and swelling that would rapidly spread, earning it the dialect names Rotlaafe—literally “the running redness,” or Wildfeier. Prior to the use of antibiotics, erysipelas is estimated to have claimed over one-third of those who contracted it,51 and conventional physicians often struggled to provide relief.

Mennig’s procedure made use of a red string to remove the illness and was widely practiced throughout the Dutch Country. His cure called out to the illness animistically, and asked it to depart: Wild Feuer, flieh, flieh, flieh. Der rothe Faden jagt dich hie! (Wildfire, flee, flee, flee. The red string chases you away!).

Figure 18: Typographical reproduction of Rev. Mennig’s Cure, based on the Roughwood Collection.

PA German Cultural Heritage Center at Kutztown University.

Mennig’s instructions continue that one must pass the string three times over the afflicted person, and each time say the indicated words. Thereafter, one must tuck the string into a piece of paper, and hide it in the chimney, where the string would be smoked by a fire. After three hours, one should take the string again and perform the procedure a second time, then place the string back into the chimney. After another three hours, the process is to be repeated once more, and then the string is cast up into the chimney. The illness will depart when the string falls where it will. The instructions conclude with a nota bene, that if the wildfire has afflicted the body, the arms, and the legs, that one must pass the string three times over each limb, the legs, the back and the front of the person, and say the words each time.

Figure 19: Aunt Sophia Bailer, Tremont, Pennsylvania, “Saint of the Coal Regions” (1870-1954).

Don Yoder Collection, Pennsylvania German Cultural Heritage Center, Kutztown University.

Sophia performs Georg Mennig’s cure for wildfire over a woodstove with a red woolen string.

This remedy proceeds from an ancient idea that like attracts like, and that a red string, representing fire, could be used to attract and remove the fiery skin infection. Likewise the smoke from the chimney would carry away the illness as it is extinguished. Furthermore, the ritual is framed as an animistic dialog between the practitioner and the disease, indicating that the infection was ultimately believed to be caused by an invasive spirit, a folk belief that foreshadows the later discovery of biological pathogens. This personification of the illness as a malicious, willful entity, or as a whole cohort of entities, is found throughout Pennsylvania Dutch powwow prayers. One particularly elaborate Pennsylvania document from 1892-93, decorated with stars and inscribed to a Lillie A. Moyer by an unnamed “friend,” describes another cure for wildfire:

“For the Wildfire to Powwow:

Wildfire and inflammation, curse and pain, running blood and gangrene, I circle thee. The Lord God protect thee. God is the highest one that can cast thee out—wildfire, inflammation, curse and pain, running blood and gangrene—and direct all harm, away from [insert baptismal name]. + + +”

Scripted as an exorcism, these prayers command the illnesses to depart by the authority of a higher source of power. Yet unlike Lillie Moyer’s powwow ritual that invokes not only the diseases but also the hosts of heaven to expel them, by comparison, the procedure endorsed by Rev. Mennig is decidedly devoid of specific Christian references. Even the tell-tale abbreviation of three crosses that typically concludes most written or printed powwow prayers is nowhere to be found on Mennig’s broadside.

Figure 20: Powwow instructions of Lillie A. Moyer for treating wildfire, Tulpehocken, Berks County, 1893. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer; formerly of the Lester P. Breininger Collection.

The typical defense for this absence of explicit Christian imagery in certain examples of powwow praxis is that an invocation of the Holy Trinity typically concludes each ritual. Beyond this, the expectation is that such rituals function as part of a broader network of sacred relationships, and that the practitioner who performs the ritual serves only as a facilitator or intermediary. This notion is echoed in one of the most celebrated of all powwow manuals, attributing the following words to St. Albert the Great: “. . . aber nicht durch mich, sondern durch Gott Vater, Gott Sohn und Gott heiligen Geist . . .”—“but not through me, rather through God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit.”52

Both Lillie Moyer’s and Rev. Mennig’s processes, which incorporate animistic and symbolic elements, are reminiscent of the exorcism rituals of the Middle Ages that were carried out by clergy and the laity. The exorcism rituals outlined in the infamous anti-witchcraft treatise Maleus Maleficarum (Hammer of the Witches) of 1487, written by Catholic inquisitors Kramer and Sprenger and sanctioned by Pope Innocent VIII, offers the following adjuration: “. . . by God who redeemed thee with His Precious Blood, that thou mayest exorcised, that the illusions and wickedness of the devil’s deceits may depart and flee from thee together with every unclean spirit, adjured by him who will judge the quick and the dead, and who will purge the earth with fire. Amen.”53

These highly elaborate exorcism rituals are not limited to Roman Catholicism, and were also once part of Protestantism. Dr. Martin Luther’s first vernacular translation of the Baptismal Rite of 1523 incorporates such elements as exorcizing evil spirits from an infant by blowing under the eyes three times, anointing the ears and nose with the minister’s spittle, and the use of salt (which was actually put into the child’s mouth), along with more formally accepted elements such anointing with oil, and making the sign of the cross. During the period of adjustment in the development of early Protestantism, elements like these were eventually removed from the liturgy.54 Each of these procedures appears in Pennsylvania Dutch folk practice: blowing is used to remove fire from a burn, and salt is a substance commonly believed to neutralize misfortune and repel evil. Both saliva and oil were historically part of powwow practice and were applied in the healing of certain childhood ailments, such as colic. Ubiquitously, the sign of the cross is used as a central feature in most powwow healing rituals to bless parts of the body that are afflicted.

Essentially, powwow doctors ministered to the sick using practices that were borrowed from liturgical tradition. It should therefore be no surprise that some pastors participated in the tradition and that any form of sanctioning from the clergy would be valued by the laity. In fact, the names and reputations of ministers are generously interwoven through powwow narratives, with representatives in many denominations.

The Lutheran Rev. Mennig’s powwow practice is mirrored by the Brethren minister Henry Schuler Long of Franconia, Montgomery County, who was known to have carried written powwow prayers in the same notebook from which he preached his sermons.55 The same is purported to have been true of the German Reformed minister Charles Gebler Herrmann of Maxatawny Township, Berks County, who compiled one of the most famous collections of German grave-side songs, Sänger am Grabe in 1842.56 On the other hand, his colleague William A. Helffrich from the same township was known to have openly discouraged his parishioners from visiting powwow doctors.57

Of all historical ministers who opposed the practice of powwow, there was none so outspoken as the Rev. William B. Raber of the Pennsylvania Conference of the United Brethren in Christ. His famous 1855 treatise The Devil and Some of His Doings describes Raber’s perception of the infernal illusions that deceived American society in his day, and includes a section on “Charms and Pawwawing.” Raber condemns powwowing as being the work of the devil, even though he acknowledges that it is based on religious principles. Instead he says that it “belongs to paganism, from whence it came, and it is unworthy of an enlightened, leaving out of the question, a Christian community.” Rev. Raber continues in a judicious tone:

“To cure by words and manipulations would be performing a miracle, and where would that supernatural power come from? The answer from every paw-wawer is, without conscience or comment—from the Lord. Well, let us see. The sixth verse of the sixteenth chapter of Ezekiel is used to stop bleeding, [When I passed by thee and saw thee polluted in thine own blood, I said unto thee, when thou wast in thy blood live, yea, when thou wast in thy blood live] by inserting the first name of the bleeding person before the word live. Now in that verse is a similitude of Jerusalem under a neglected, wretched infant. Apply that to an individual with a bleeding nose, or otherwise, and Holy Writ is violently wrestled out of its original meaning, by which a miracle is to be performed. Will God do such a thing? Is it in accordance with his character as God, or commensurate with the truthful nature of his attributes? My dear reader! Such things are not from God. He cannot agreeably with his veracity as God, bless a wrong application of his Holy Word to perform a miracle.”58

Rev. Raber’s position is not so much a criticism of the use of scripture for healing, but the manner in which it is applied, and the aesthetics that create the ritual structure of powwow practice. This very criticism however, focuses on an excellent example of the adaptability of scriptural comparison for the purpose of healing, despite the reverend’s disagreement. The symbolic comparison of the city of Jerusalem to an abandoned, suffering infant “polluted” in its own blood that is described in the Book of Ezekiel, is used in powwowing to create yet another comparison, in this case of the bleeding person, who is often referred to as a “child of God,” in powwow prayers. This comparison is not meant to undermine the authority of scripture, but to apply it in a meaningful way to alleviate suffering and properly place the healing experience within a religious context.

Although Rev. Raber suspects that such an application of words is evidence of paganism and a corruption of biblical interpretation, on the contrary, this particular use of scripture is often pointed to as one of the simplest examples of biblically-based ritual healing among the Pennsylvania Dutch. This particular verse of scripture was printed as a popular powwow broadside, and is sometimes found written out longhand among family papers, or marked in the margins of folio Bibles.59

Still other critics of powwow take a different perspective. Dr. J. H. Myers wrote for the American Lutheran in 1870, calling powwow “superstition”—except that he differentiates what he calls the “undeniable” healing resulting from the actual words that are used. Dr. Myers claimed that the healing is actually achieved through the laying on of hands, and that the words were only a veneer that shrouded an otherwise sound, Christian healing practice.60

In each case, both Rev. Raber and Dr. Myers represent official denominational doctrines, and they judge the practice of powwow based upon its divergence from their own religious expression, using similarity as their basis for determining its degree of correctness. Beyond this, both ministers redefine powwow according to their own religious schematics and relegate the tradition to categories that fail to accurately describe it. In order to emphasize the degree of incorrectness that both ministers assume, they alternately portray powwow as either a devil-induced delusion or as an ignorant superstition. While the latter term is markedly less harsh, superstition is still a prejudiced term, implying beliefs worthy of denigration. Often the term is used to denote beliefs held by others, and is rarely self-reflective. While these forms of criticism are perhaps to be expected, such attitudes ignore the place of powwow practice as part of a continuum of religious belief.

Ritual Literature of Pennsylvania

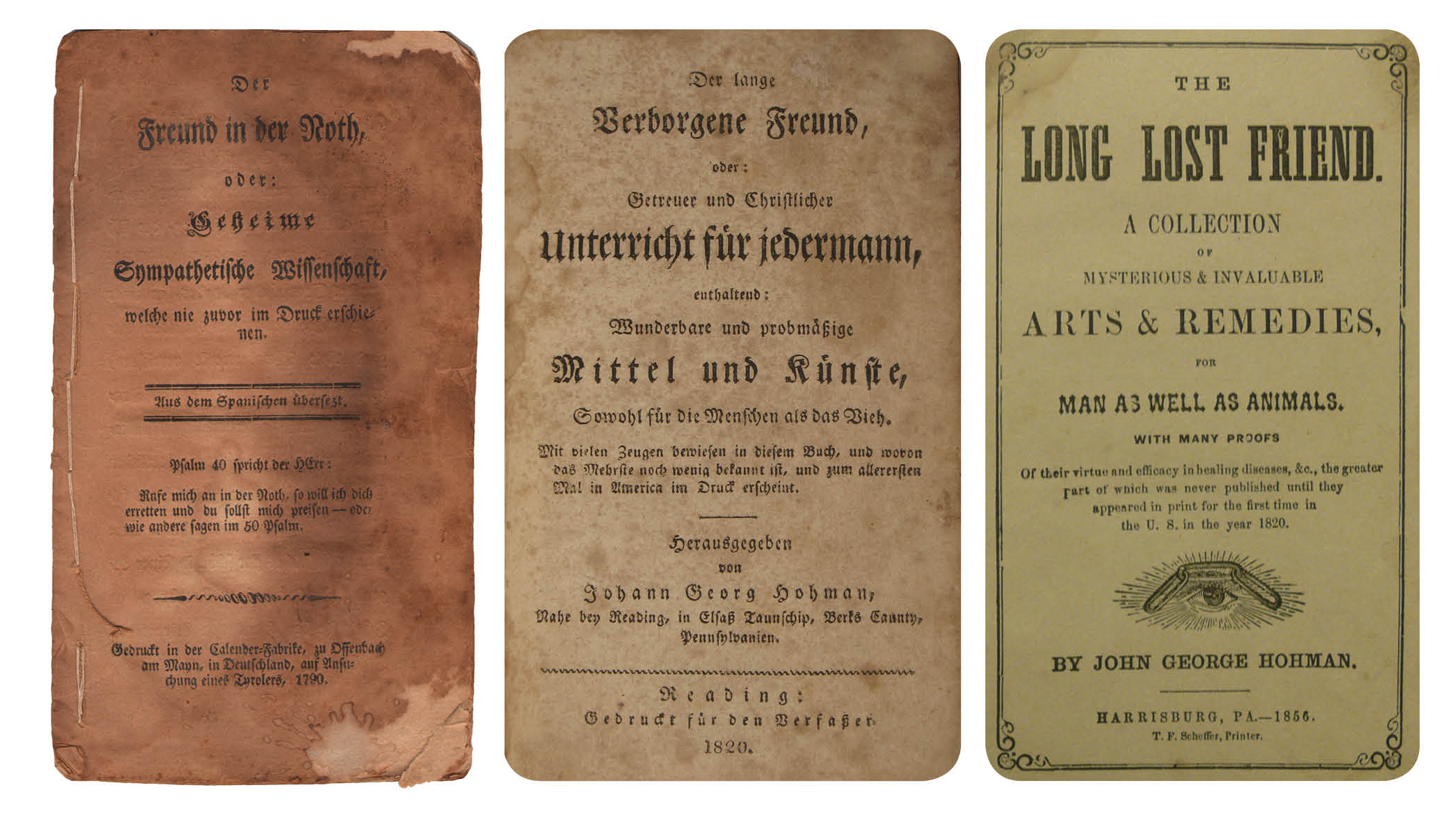

Despite the fact that powwowing is mostly informed by oral tradition, a wide range of literature has accumulated on the subject in Pennsylvania, and much of this material derives directly from European sources. The most widely circulated book on both sides of the Atlantic is attributed to the Swabian bishop, St. Albert the Great, entitled Albertus Magnus bewährte und approbirte sympathetische und natürliche Aegyptische Geheimnisse für Menschen und Vieh (Albertus Magnus’ Tried and Approved Sympathetic and Natural Egyptian Secrets for Man and Beast), which provides remedies and rituals for the purpose of healing, as well as a lengthy introduction pertaining to the use of ritual to counteract the works of the devil and his servants.

One of the most celebrated and widely used blessings against malicious curses is attributed to St. Albert the Great (translated from the original German):

“If a human or animal is plagued with evil spirits, how to restore him and make him whole:

Thou arch-sorcerer spirit, thou hast assailed N.N., so withdraw away from her, back into thy marrow, and into thy bone, so it was spoken to thee, I dismiss thee, by the five wounds of Jesus, thou evil spirit, and I dismiss thee, by the five wounds of Jesus, thou evil spirit, and I dismiss thee by the five wounds of Jesus from this flesh, marrow and bone, I dismiss thee, by the 5 wounds of Jesus at this very hour, let N.N. become well again, in the name of God the Father, of God the Son, and of God the Holy Ghost, Amen.”61

(N.N. implies that one should insert the name of an unknown person, and is a Latin abbreviation for nomen nescio, literally “I do not know the name.”)62

It is highly unlikely that this work was actually written by St. Albert the Great, who was distinguished for his philosophical and academic contributions to Europe as a Doctor of the Roman Catholic Church. Nevertheless, a whole body of pseudo-epigraphical folk-medical literature developed around this influential saint, such as Secretis Muleorum (Women’s Secrets), a popular work of midwifery, and his alleged collected works The Book of Secrets describing the virtues of herbs, minerals, and animals for ritual purposes. Some of the earliest manuals of powwowing practice in Pennsylvania were also works of midwifery attributed to the saint, such as Kurzgefasstes Weiber-Büchlein. Enthält Aristoteli und A. Magni Hebammen-Kunst (Concise Women’s Booklet, Containing the Midwifery of Aristotle and Albertus Magnus), printed in the 1790s by the brotherhood at the Ephrata Cloister.

Figure 21: Left: Portrait of St. Albert the Great, alleged author of several works of medicine, midwifery, and magic. Heilman Collection of Patrick J Donmoyer.

Right: Kurzgefaßtes Weiber-Büchlein. Enthält Aristotels und Alberti Magni Hebammen Kunst (Concise Little Book for Women, Containing the Midwifery of Aristotle and Albertus the Great), Ephrata, PA 1791. Heilman Collection of Patrick J. Donmoyer, formerly of the Lester P. Breininger Collection.

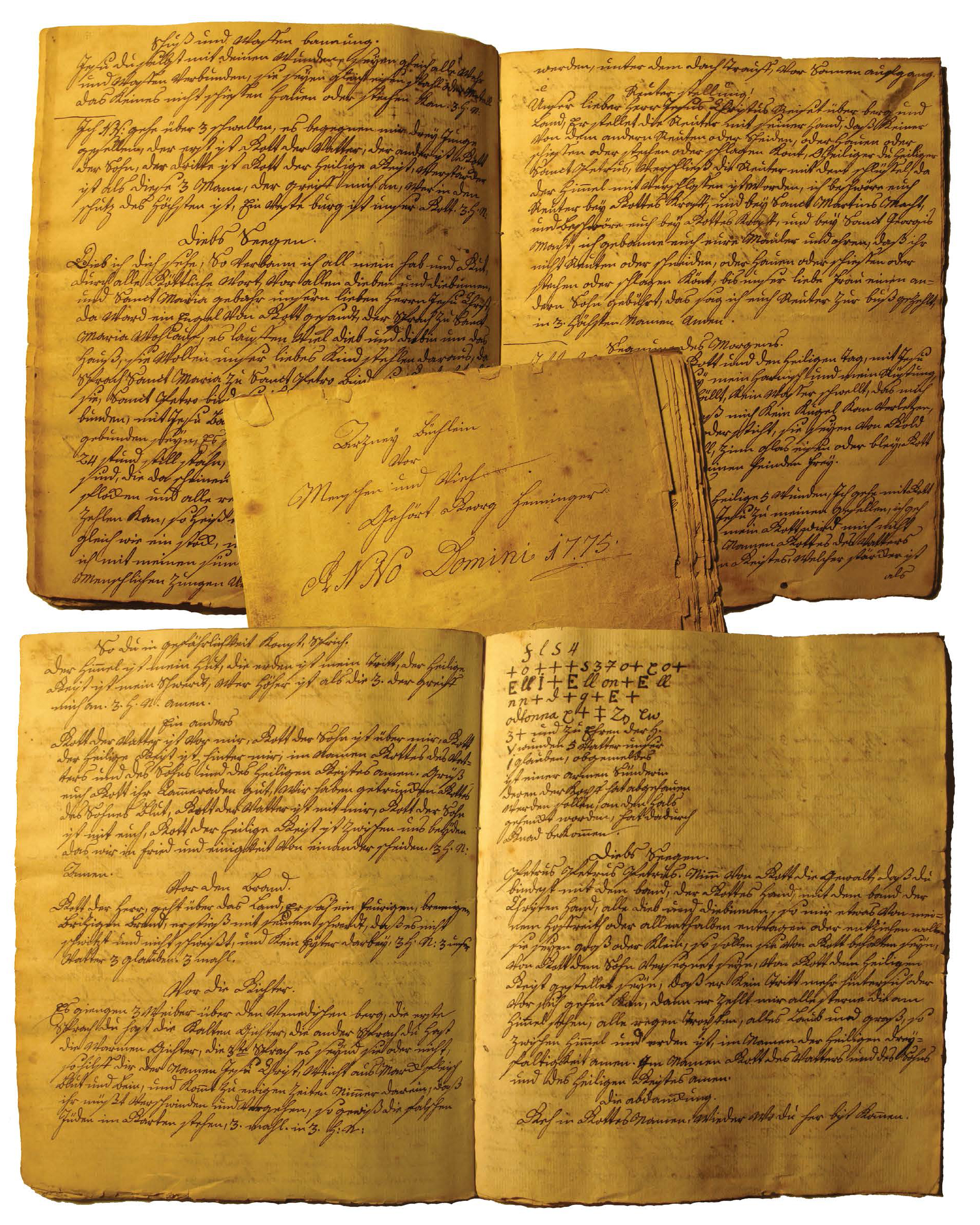

The earliest known work of powwow ritual procedures produced in Pennsylvania is the 1775 manuscript of Johann Georg Henninger (1737-1815). Henninger was an Alsatian emigrant and the son of a weaver Johan Martin and his wife Anna Catharina (Fuchs) Henninger, born on April 13, 1737, in the small town of Hatten, just a mere ten miles west of the Rhine River. In 1763 he crossed the Atlantic aboard the ship Chance, and made his way to Albany Township, Berks County, where it is likely that he penned his manuscript.63

Henninger’s work consists of two parts: The first is a series of lengthy transcriptions from a European medical booklet, Kurtzgefasstes Arzney Büchlein für Menschen und Vieh (Little Book of Medicine for Man and Beast), first printed in Vienna and later reprinted at the Ephrata Cloister in 1791. Henninger’s manuscript was produced prior to this American publication and contains chapters for horses, cows, pigs, and humans, with copious additions not found in the Ephrata imprint. Henninger’s second part is the most significant, consisting of rare, previously unpublished blessings used for stopping blood and convulsions, healing burns, protection from calamity and criminal violence, and compelling thieves to return stolen property. He also includes inscriptions to be carried on one’s person to avoid false accusations, prayers for invisibility in times of danger, and instructions for creating a ceremonial knife marked with nine crosses used in rituals for protection.