Glencairn Museum News | Number 1, 2018

Amid the many fine artifacts in Glencairn Museum’s ancient Egyptian collection, which includes statuary, reliefs, and sarcophagi, there is a category of objects which arguably have a very personal connection to their original owners—the collection of Egyptian jewelry. These are objects which, in ancient times, were worn on a regular basis by individuals for reasons both spiritual and aesthetic. In addition to looking attractive and decorative, much of ancient Egyptian jewelry had protective functions. Further highlighting the importance of these items to their owners, these adornments were included in their owners’ burials, placed in the tomb with the deceased so that they could continue to adorn and protect them in the afterlife.

When considering the Glencairn jewelry collection, which consists largely of strung beaded necklaces, amulets, and rings, it is important to keep in mind that the way in which these bead strings appear today is not the way in which the strings looked in ancient times. The jewelry in the Glencairn collection was purchased over the years by Raymond Pitcairn from Azeez Khayat and his son, Victor Khayat, antiquities dealers who would restring ancient beads in styles or designs that would be attractive to the early twentieth century/modern collector (and no doubt profitable to the antiquities dealer!). This was not an unusual practice. Even today, beads found in excavated archaeological contexts are often restrung in an approximation of what the original pattern may have been. The reason for this is that the material on which the beads were originally strung was organic, likely thread made of flax, and this material is fragile and has a tendency to decay, even in Egypt’s dry climate. When archaeologists find beads, they are often in a scattered deposition, rather than in carefully laid out rows. Individual elements of jewelry in the collection date at least as early as the First Intermediate Period (2130-1980 BCE) through the Greco-Roman Period (332 BCE- 323 CE).

Symbolism: Color and Material

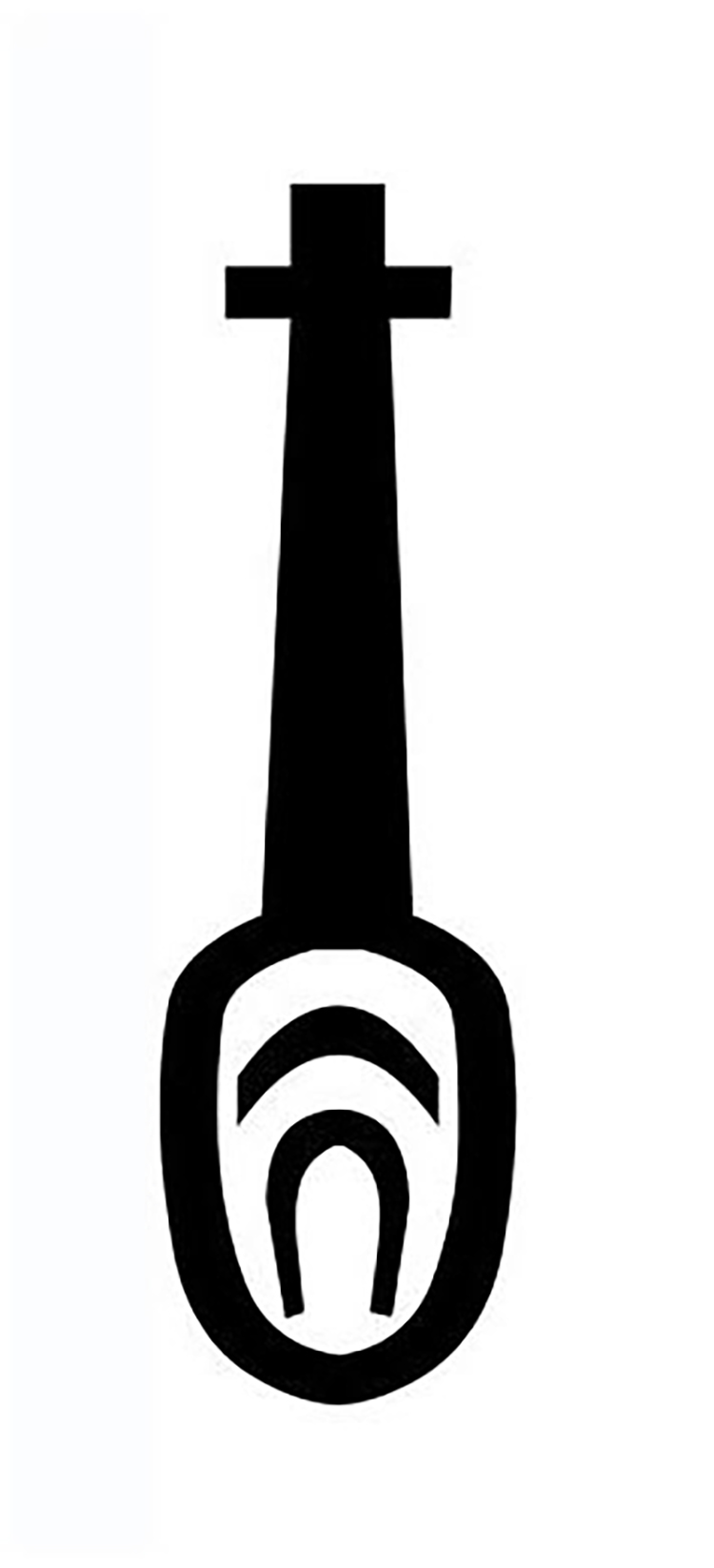

There are a number of ways that these ornaments may have afforded protection to their wearer. First, we can consider the images represented in the form of amulets. These small images can take the shape of deities, animals, birds (which often had a divine association), human body parts, floral designs, and individual hieroglyphic signs representing words with positive or protective meanings. Secondly, we can bear in mind that color symbolism was important to the ancient Egyptians. Color had meaning. Some colors were associated with the sun and the solar aspects of Egyptian religion. Other colors were connected with the idea of rebirth or regeneration. Certain Egyptian amulets were supposed to be made in a particular color, such as the tyet amulet (Figure 1), also known as the Isis knot (Gardiner sign list V39). This amulet is usually made of a red colored material (Figure 2). Therefore, the various hues that these amulets or beads take adds another layer of magical protection for the wearer.

Figure 1: The hieroglyphic sign tyet, known as the Isis knot (Gardiner sign list V39), may represent knotted straps (see also Figure 2).

Figure 2: Red jasper tyet amulet from the site of Abydos (see also Figure 1). Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 00.4.39.

Finally, related to the meanings that different colors had for the ancient Egyptians, it is important that we also take into account the materials of which these objects are made. The jewelry in the Glencairn collection represents a variety of materials. Some of the most commonly seen are: Faience, Carnelian, Amethyst, Lapis Lazuli, Glass, Gold, and Bone (Figure 3). We can consider the raw materials for the colors they display (carnelian is red; turquoise is blue) as well as for the expenses incurred by the ancient Egyptians in using a particular material. Certain materials such as lapis lazuli (Figure 4), a semi-precious stone with a dark blue color (often with flecks of gold-colored inclusions), was a very expensive commodity that had to be imported into Egypt from as far away as Afghanistan. Similarly, there are locations within Egypt where gold can be found, but much of the gold used in Egyptian jewelry was sourced from mines in Nubia, located to Egypt’s south. Other materials were less costly. Carnelian, for example, could be sourced locally in the Egyptian desert (although its quality varies greatly from a deep red to a pale orange). Another very common material present in the Glencairn collection is faience. Egyptian faience is a man-made composition comprised of crushed quartz that self-glazes when fired. It was produced in a variety of colors, and perhaps the Egyptian craftsmen used this material at times to imitate costlier materials of the same hue. Most of the faience objects in the Glencairn collection were made in ceramic molds (Figure 5).

Figure 3: This detail of necklace (Glencairn Museum 15.JW.184) illustrates the variety of semi-precious stones used by ancient Egyptian jewelers including amethyst, carnelian, lapis lazuli and turquoise.

Figure 4: Golden inclusions can be seen in this sample of lapis lazuli. Image courtesy of Hannes Grobe.

Figure 5: Faience amulets were often mass-produced in ceramic molds, such as this example in Glencairn Museum (E522) depicting a wedjat eye.

Amulets and Representations

Let’s now take a look at the form of some of the amulets and pendants present in the bead strings in the Glencairn collection and consider the symbolic and religious meanings behind them. We can first turn to the deities who are represented:

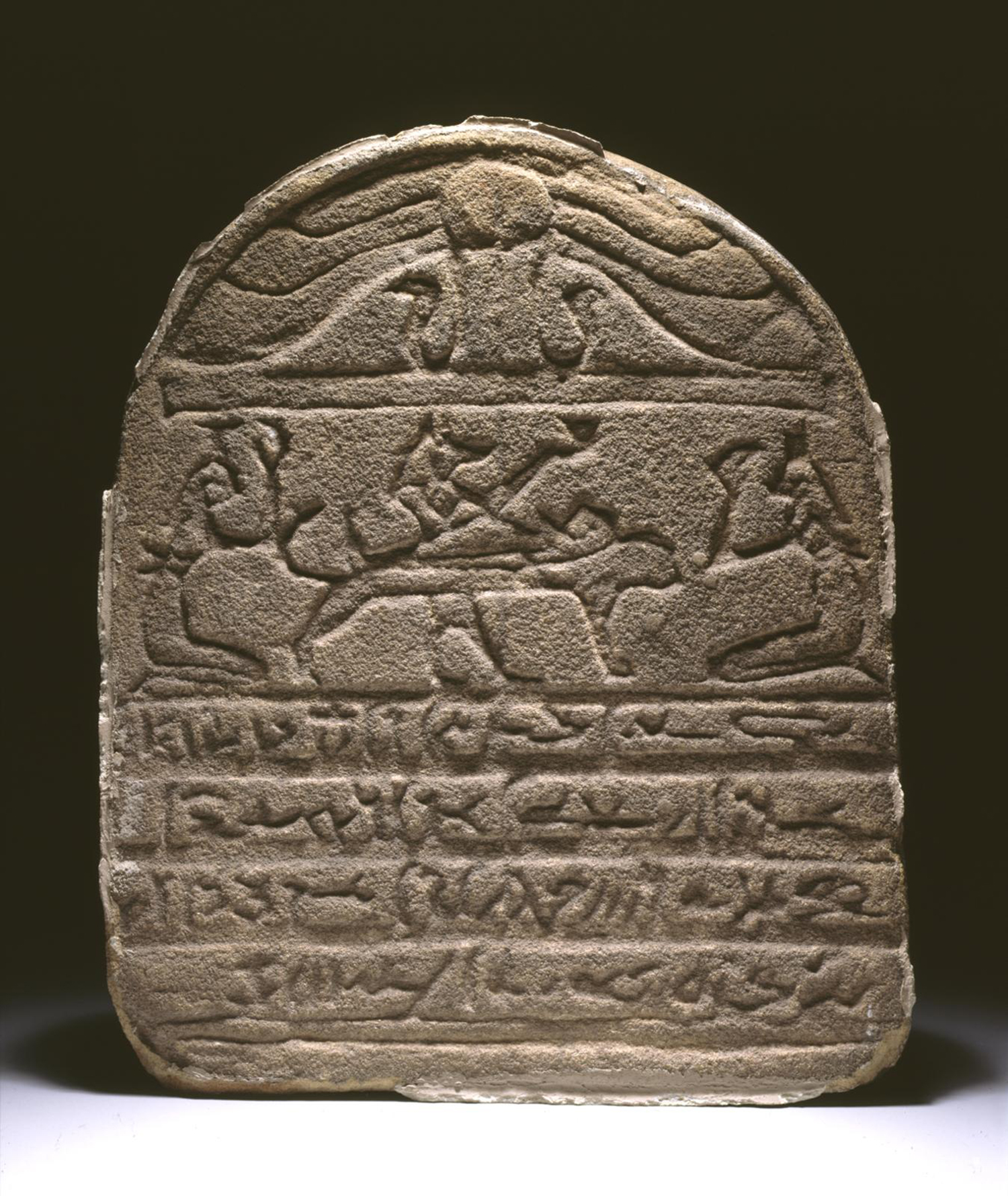

Figure 6: Anubis. Usually appearing as a jackal, or a man with a jackal head, Anubis (amulet at center) was a funerary deity closely connected to mummification. According to myth, after Isis and Nephthys collected the dismembered pieces of Osiris, Anubis assisted them in putting the god back together again, binding his body parts with linen and thereby creating the first mummy (see Figure 7). Glencairn Museum 15.JW.12.

Figure 7: Anubis. This god is often shown attending to the mummified deceased. Individuals may have wanted amulets of Anubis to offer protection to their mummified remains (see Figure 6). A funerary stela from the site of Dendereh shows Anubis attending to the mummy of the deceased; Isis and Nephthys flank either side of the funerary bier. Image courtesy of Penn Museum, E2983.

Figure 8: Bes. Despite his somewhat ferocious appearance, this dwarf god with a leonine face was a protective force who warded off evil with his expressive grimaces and with the knives he often carried. A protector of the household, Bes was also a guardian of mothers and children. Often shown with musical instruments, Bes had connections to celebration and fertility. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.17.

Figure 9: Bes. The Glencairn collection has Bes amulets which depict Bes fully (Figure 8 above, 15.JW.17) and others which take the form of only his head (15.JW.241), highlighting his grimacing visage.

Figure 10: Horus. The son of Osiris and Isis, Horus was the heir to his father’s throne. Horus was a god of kingship, and the reigning pharaoh was thought to be his manifestation on earth. Usually depicted as a man with the head of a falcon, Horus could also be shown fully in falcon form. In several examples in the Glencairn collection, amulets of falcons wearing the double crown certainly depict this deity. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.345.

Figure 11: Re-Horakhty. The Egyptians had a number of solar deities, or figures thought to represent a sun god (see Figure 12). Like Horus, many of these sun gods take the form of falcons. In contrast to the falcon wearing the double crown (Figure 10), amulets of a falcon wearing the circular sun disk on its head probably depict the solar god Re-Horakhty. In addition to crowned falcons, the collection also has amulets of falcons without any identifying headgear. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.233.

Figure 12: Re-Horakhty. Tasheryt, the Chantress of Amun, worships the god Re-Horakhty (see Figure 11) on this painted wooden stela. The god is identified by name in the hieroglyphic inscription. Image courtesy of Penn Museum, E2043.

Figure 13: Sekhmet. One of the most popular goddesses, Sekhmet takes the form of a lioness or a lioness-headed woman. A fierce and warlike goddess, she can also exhibit a protective side. There are a number of goddesses who can be depicted as lionesses, including Mut, Pakhet, and Tefnut. The peaceful domestic cat goddess, Bastet, can also appear in leonine form. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.130. (For more on Egyptian lions and cats at Glencairn, see Cats, Lions, and the Fabulous Felines of Ancient Egypt in Glencairn Museum News No. 7, 2015.)

Figure 14: Taweret. Pregnant and nursing women used amulets of Taweret to protect themselves and their babies from evil spirits. Like Bes, this goddess is fearsome in appearance, combining the physical attributes of the hippopotamus, crocodile, and lion. Glencairn has a number of beaded necklaces which incorporate Taweret amulets, including this one with fifteen gold amulets showing the goddess in profile. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.573. (For more on Taweret at Glencairn, see The Goddess Taweret: Protector of Mothers and Children No. 9, 2014.)

Figure 15: Thoth. The god of wisdom, the patron of scribes, and the inventor of writing, Thoth is usually shown as an ibis bird, or an ibis-headed man. Thoth can take the form of a baboon as well as an ibis. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.434.

Other Images and Symbols

In addition to images of gods and goddesses, there are other magical and protective images that appear on amulets in the Glencairn collection. Let’s take a look at some of these symbols:

Figure 16: Aegis with Lioness. The larger object in this photo is an aegis, or shield, with a depiction of the head of a leonine goddess, probably Bastet or Tefnut, wearing a sundisk crown with a rearing uraeus. The bottom part of the aegis is a stylized form of a beaded wesekh (or “broad”) collar (see Figure 17). The aegis is a protective symbol, and this example was made by beating a thin sheet of metal (probably gold) into a mold. The detail on this amulet is exquisite. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.179.

Figure 17: Aegis. This bronze aegis (see also Figure 16) takes the form of the head of a female deity atop an oversized broad collar. Image courtesy of Penn Museum, E13001.

Figure 18: Djed Pillar. The djed hieroglyph (Gardiner signlist R11) is a word translated as “stability” (see Figure 19). The symbol came to be connected with the backbone of the god Osiris.

Figure 19: Djed Pillar. Amulets of djed pillars (see Figure 18) are very common and were popular funerary talismans. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.574.

Figure 20: Djed Pillar. Representations of Djed pillars first appear in the late Old Kingdom (ca. 2350 BCE) and were often placed within the wrappings of a mummy to ensure protection for the deceased (see Figures 18, 19). The back of this cartonnage mummy case of a priest named Nebnetcheru features a large image of a djed pillar, which would provide magical protection for his body. Image courtesy of Penn Museum, E14344B.

Figure 21: Fish. Glencairn necklace 15.JW.43 features an amulet of a fish. Given the importance of the Nile River, it is not surprising that fish imagery is found in amulets. One type of fish, the tilapia, was a symbol of rebirth and regeneration. Fish amulets may also have been worn to protect one from drowning. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.431.

Figure 22: Fish. A famous Egyptian tale describes a young woman who is upset at losing her fish pendant in the water while taking part in a royal boating party. She refuses to row until she gets her fish pendant back. A lovely cosmetic jar in the British Museum (EA2572) shows a fish-shaped pendant affixed to the braid of a kneeling young woman (see also Figure 21). Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Figure 23: Floral Elements. Many of the Glencairn necklaces feature floral elements. Most are made of faience and may have originally come from elaborate broad collars with a floral design. These faience collars imitate actual floral collars, which may have been worn on festive occasions during life and were certainly used as decoration in funeral settings (see Figure 24). Glencairn Museum 15.JW.515.

Figure 24: Floral Elements. Certain flowers were of special importance to the Egyptians. The lotus (or more correctly, the water lily) was a symbol of rebirth and regeneration. The mandrake had sensual undertones and may have been considered an aphrodisiac. Cornflowers and poppies are also represented in the faience beads at Glencairn. This floral collar made from papyrus, olive leaves, persea leaves, and nightshade berries was found in Tutankhamun’s embalming cache, and may have been worn by a mourner at his funerary banquet. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 09.184.216.

Figure 25: Fly. The humble (and bothersome) fly was a popular form for amulets. Usually given as a reward for brave service in battle, the fly amulet may have represented a wish for resilience. It is also possible that small fly amulets may have been worn in the hope of warding off pesky attacks from these flying creatures. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.390.

Figure 26: Nefer-sign. The word nefer, perhaps best known to many as an element in the name Nefertiti, meant “beautiful” (see Figure 27). The sign (Gardiner signlist F35) depicts an animal’s heart and windpipe.

Figure 27: Nefer-sign. Nefer (see Figure 26) ornaments are frequently found on collars and are usually made of gold, as are the Glencairn examples. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.254.

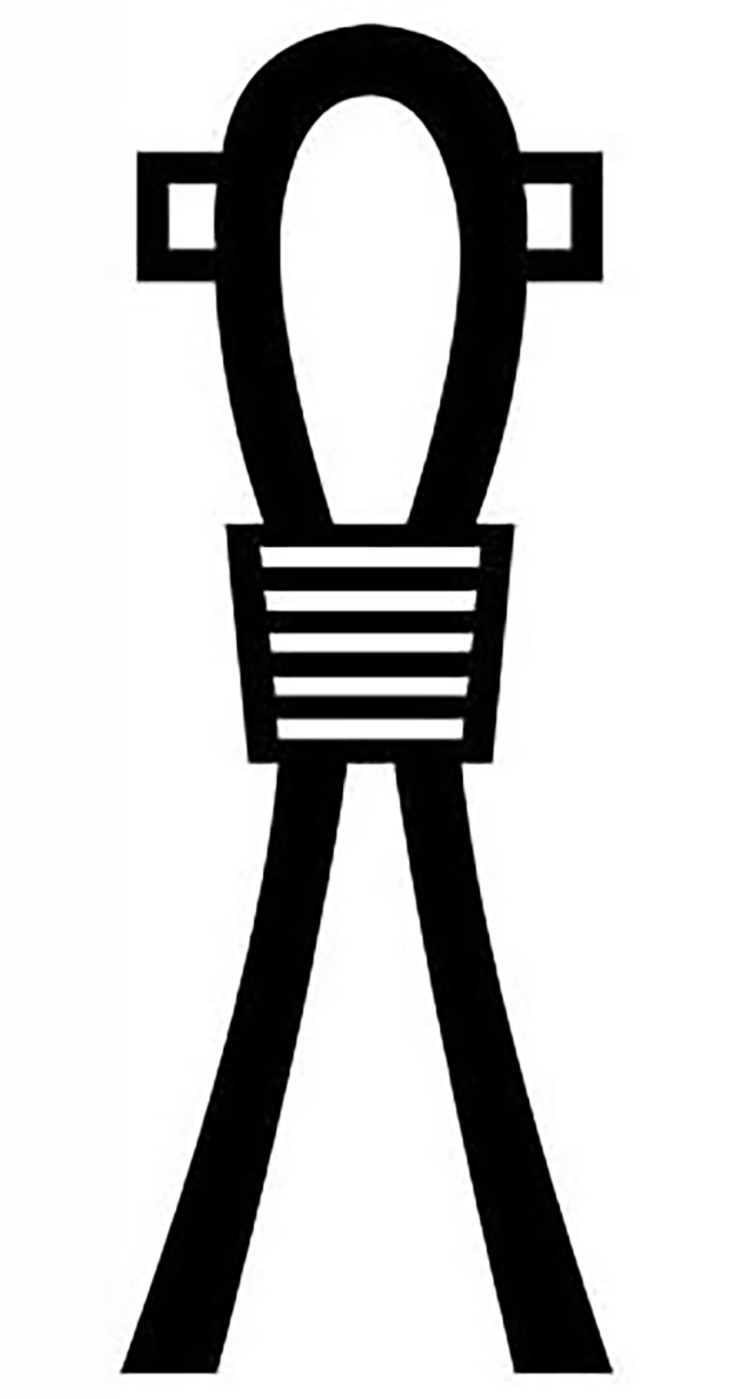

Figure 28: Sa-symbol. This hieroglyph (Gardiner signlist V17, var. V18) may represent a type of life preserver, perhaps made of papyrus or reeds (see also Figure 29). We frequently find this hieroglyph in combination with images of the goddess Taweret.

Figure 29: Sa-symbol. The hieroglyph on this amulet reads “s3,” which is translated as “protection” (see Figure 28). Glencairn Museum 15.JW.342.

Figure 30: Stars. The ceilings of tombs and temples in Egypt were often decorated with yellow five-pointed stars on a blue background to represent the night sky (see Figure 31). One of the Glencairn necklaces includes several star-shaped amulets made of turquoise-colored faience. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.348.

Figure 31: Stars. Here a field of yellow stars on a blue background decorates the ceiling in a chamber in Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple at Deir el Bahri. While the star is common in architectural decoration, its appearance as an amulet is not (see Figure 30). Image © Ad Meskens/ Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 32: Papyrus Column. Amulets of papyrus (or wadj) columns were very popular in ancient Egypt. Papyrus was a riverine plant that thrived in ancient times (and was the material out of which the writing material of the same name was made). This type of amulet is usually made of material with a greenish color (whether faience or stone), and to the Egyptians the color green was emblematic of life and the potential for rebirth. There are specific magical spells associated with amulets of this shape. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.506.

Figure 33: Wedjat Eye. Perhaps the most popular of all Egyptian amulets, the wedjat eye, or the “eye of Horus” amulet, represents the eye of that god, which had been damaged in a battle with his uncle, the god Seth (see also Figure 34). The injured eye was restored by means of magical powers and became whole and healthy again. The word wedjat means “healthy” or “sound,” and this amulet was worn as a wish for protection and health. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.534.

Figure 34: Wedjat Eye. There are quite a few examples of wedjat eye amulets and rings in the Glencairn collection, made of a variety of materials, several turquoise-colored faience amulets (see Figure 33), and this example, made of strips of gold. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.191.

In addition to the amulets mentioned above, a few other categories of objects found in Glencairn’s jewelry collection bear mention. When one examines the collection as a whole, one notices that there are quite a number of scarab (dung beetle) amulets strung on necklaces (Figures 35, 36, 37). The scarab was an important symbol for the ancient Egyptians. On one hand, the scarab was a solar symbol. The Egyptians were keen observers of nature and witnessed dung beetles pushing balls of dung across the sand. They conceived of the idea that there was a beetle that pushed the sun across the sky as the daytime hours passed. At the same time, they also observed young beetles hatching from these dung balls and thought of the scarab as a symbol of rebirth and regeneration.

Figure 35: This somewhat stylized scarab amulet is made of lapis lazuli. Glencairn Museum 15.JW.298.

Figure 36: This realistically carved scarab amulet is made from stone (Glencairn Museum 15.JW.569).

The scarab amulet came to be used as a sort of seal. The scarab amulet is usually pierced longitudinally to allow it to be strung or to be incorporated into the bezel of a ring. The upper side of the scarab seal was decorated like a beetle (Figure 36), while the flat underside bore incised decoration (Figure 37). Sometimes these designs are purely decorative—with spiral designs, for example. Sometimes there are protective images or short texts. At other times the bottom of the scarab contains the name and titles of its owner and would have functioned like a signet ring, to impress the seal of its holder into mud or clay. In this way the seal served two purposes: there was a magical association with the idea of rebirth, and there was also a practical, perhaps administrative function with its use to mark ownership when used to seal things.

Figure 37: The decoration on the underside of this scarab features a seated baboon representing the god Thoth. He faces the name of the pharaoh Tuthmosis III in a cartouche. The text at the top calls the king the “good god, the Lord of the two lands.” Glencairn Museum 15.JW.569.

Many of the beads in the Glencairn collection are what Egyptologists refer to as “mummy beads.” These are thin, tubular beads made of faience. While it is possible that some of these were originally strung in a long string, it is more likely that these tubular beads were originally part of either beaded broad collars known as wesekh collars (Figure 38) or parts of elaborately beaded net shrouds which covered mummies (Figure 39).

Figure 38: Excavated at the site of Meydum, this beautiful broad collar (wesekh) is made of blue and black faience. Each end of the collar is decorated with a terminal in the shape of a falcon head. Both men and women wore necklaces like this in ancient Egypt. Image courtesy of Penn Museum, UPMAA 31-27-303.

Figure 39: Some mummies were covered with shrouds made of beaded netting. These tubular beads are made of faience and are often referred to as “mummy beads.” Image courtesy of Penn Museum, UPMAA E2179.

Finally, one should mention a small group of a particular bead-type represented in the collection. From a technological perspective, some of the most remarkable beads in the Glencairn collection are the Roman period glass mosaic face beads. These multicolor round beads are decorated with miniature depictions of human faces. They were painstakingly created by ancient craftsmen using canes of glass (Figure 40). The detail on these beads is incredible!

Figure 40: This glass mosaic bead (Glencairn 15.JW.77) features a tiny, detailed face. Beads like these were made by flattening a sliced section of complex mosaic glass canes.

The Egyptian jewelry collection at Glencairn provides ample opportunity to study ancient Egyptian religious beliefs and magical practices. By examining the materials and symbols present in these ornaments, one can come away with a deeper understanding of the complex thoughts that guided the artists and craftsmen in the creation of these objects, as well as the hopes and beliefs of those who wore them in ancient times.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Associate Curator, Egyptian Section

Penn Museum

Photography of Glencairn’s ancient Egyptian jewelry courtesy of Edwin Herder.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.