Glencairn Museum News | Number 7, 2018

Limestone figure of a sleeping woman using a headrest in the collection of Glencairn Museum (E1219).

Much of what we know about ancient Egyptian household furnishings comes to us from grave goods buried with the deceased for use in the afterlife. While certain tomb goods were made specifically for the burial, many other objects placed in tombs were used by the deceased during their lifetimes. This material includes articles like jewelry and weaponry, stone and ceramic vessels, clothing, and household furnishings like beds, chairs and chests.

Figure 1: Glencairn’s collection includes a simply carved wooden headrest from ancient Egypt (E1149) with traces of painted decoration.

Figure 2: Several 20th-century African headrests in the collection of Glencairn Museum.

Figure 3: An example of a stoneware Chinese headrest in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Gift of Nasli M. Heeramaneck (M.73.48.83). Image courtesy of http://www.lacma.org/.

One category of household furnishings—the headrest—looks remarkable to the modern American eye (Figure 1). However, headrests may not seem unusual to modern peoples in other parts of the world who make use of objects like these on a daily basis. For example, headrests are still used today by some African groups (Figure 2). The ancient Egyptian equivalent of a pillow, the headrest was used to support the head while sleeping. Broadly speaking, cultures—both ancient and modern—who use headrests share some characteristics that might make the use of this type of head support more practical. We see the use of headrests in climates that are hot. By lifting the head and neck above the sleeping surface, air currents can flow under the head and cool the sleeper. Groups whose cultural expressions involve the wearing of elaborate hairstyles also make use of headrests to protect their coiffures from being disturbed during sleep. For example, we find the use of ceramic “pillows” (Figure 3) during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644 CE) in China when elaborate female hairstyles were in vogue. Another practical consideration may have to do with pest control. Cloth pillows or bolsters padded with organic materials may inadvertently encourage insect infestations in certain environments. It can be assumed that all three of these factors would have been of concern to people living along the banks of the Nile thousands of years ago.

Figure 4: Headrests were made of a variety of materials, including wood, ceramic, and stone. Here from the collection at the British Museum (EA30413) is an elegant example of an Old Kingdom (ca. 2300 BCE) headrest fashioned from calcite (also known as Egyptian Alabaster). Image courtesy of The British Museum.

Headrests have been found in Egyptian tomb assemblages from the Early Dynastic Period (3000-2625 BCE) through the Ptolemaic Period (ca. 305-30 BCE), attesting to their long use in ancient Egypt. Examples found in museum collections around the world are made from a variety of materials such as wood, ceramic, ivory, and stone (Figure 4). While there is variation in form, there are some design elements that are standard. The headrest has a flat base that is typically wider than the upper portion, and the headrest features a concave section on its upper side used to cradle the head of its user.

Figure 5: Hatnefer’s Chair, Rogers Fund, 1936, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 36.3.152. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

For the ancient Egyptians, however, the headrest was imbued with more than just a pragmatic application. Religious and magical beliefs permeated all aspects of Egyptian life, and objects created for use in day-to-day life (as well as objects created specifically for burial) often had a religious or magical purpose as well as a utilitarian function. Often this magical protection came from the form of, or decoration on, the object. Household furnishings such as beds, chests and chairs were decorated with hieroglyphic motifs that afforded wishes for protection. For instance, there is a chair in the Metropolitan Museum of Art that belonged to a woman named Hatnefer (Figure 5) who lived during the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt’s New Kingdom (ca. 1492–1473 BCE). This wooden chair with a woven cord seat is decorated along the back with a series of protective images. In the center is the god Bes. Unusual in appearance, he was a dwarflike god with somewhat gruesome leonine features. Despite his outwardly threatening-looking visage—he also usually brandishes knives and sticks out his tongue—he was a protector of the home. Alternating djed pillars and tyet amulets flank the image of the deity. The djed pillar represented stability and had associations with the god Osiris. The tyet amulet, another protective image, was closely connected with the goddess Isis. These images would have acted magically to safeguard the person sitting on the chair.

Figure 6: Mirror with a Hathor head handle, Fletcher Fund, 1919, 1920, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 26.8.97. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC.

Another example of a common type of household object that often displays a religious or magical motif is the mirror. The goddess Hathor was a protector of women and a goddess of fertility, sexuality, and love. Mirror handles frequently took the form of a Hathor head (Figure 6). One can imagine a woman using this mirror and hoping to see an image that reflected the beauty of this goddess while offering the user her divine protection.

Figure 7: Jewelry Chest of Sithathoryunet, Purchase, Rogers Fund and Henry Walters Gift, 1916, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 16.1.1. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC. This wooden jewelry chest combines Hathoric imagery on its lid and elongated djed pillars along the sides. These decorations, while aesthetically pleasing, also had deeper religious meaning.

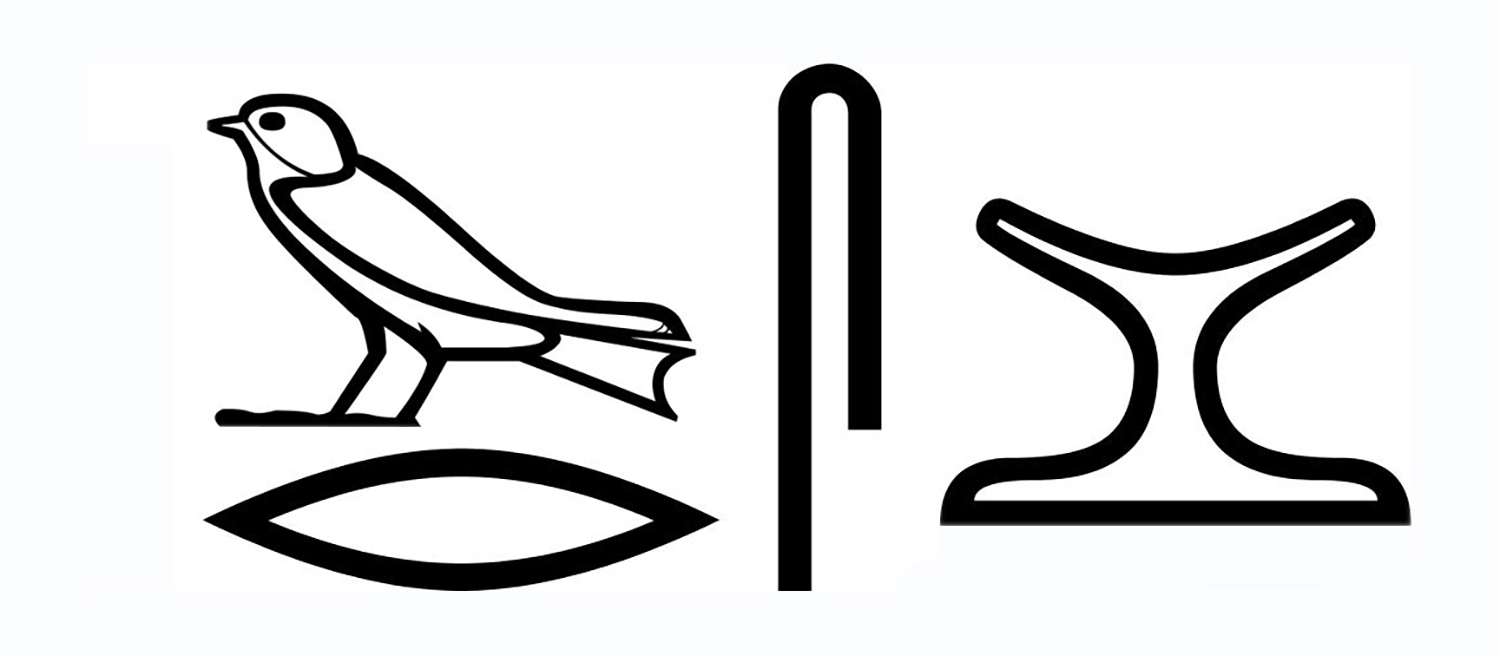

Figure 8: The Egyptian word for “headrest” in hieroglyphs.

Figure 9: The Egyptian word for “awaken” in hieroglyphs.

Figure 10: The Egyptian hieroglyph for "horizon."

The decoration of these objects has a practical function, combined with a magical or religious component designed to protect the user by associating them with the deity or concept referenced in the decoration (or shape) of the object (Figure 7). We can see this intention clearly with the form and design of the ancient Egyptian headrest. The ancient Egyptian word for “headrest” was wrs (Figure 8). This word may be related to rs, the word for “to awaken” (Figure 9). It has been observed that the shape of most Egyptian headrests echoes the form of the hieroglyph for “horizon,” the akhet, where the sun is reborn each day (Figure 10). When one considers this hieroglyph, one can see the similarity of this shape to that of a person’s head resting atop a headrest. Just as the horizon is the location of the birth of the sun (and therefore, the sun god) anew each morning, the headrest could magically be thought of as the location of its user’s (continual) rebirth— after sleeping while alive, and eternally after death. Perhaps, too, there could be an assimilation with the sun (the circle in the akhet horizon hieroglyph, representing Re, the sun god) with the head of the sleeper, and consequently the individual is connected in a special way with the sun god.

Figure 11: One of eight headrests found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, this elaborately carved ivory headrest depicts the god Shu supporting the carved element where the king’s head would have rested. This headrest is in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (JE620-20). Photo courtesy of Jon Bodsworth.

Figure 12: Magical amulets in the form of headrests were popular during Egypt’s Late Period (662-332 BCE). Glencairn has an example of one of these amulets (E519) in its collection made of hematite, a dark stone.

A particularly evocative version of this concept can be seen on a headrest from the tomb of Tutankhamun. The boy king was buried with eight headrests, including one designed with its support pillar in the shape of a male figure lifting up the curved part of the headrest (Figure 11). This figure may represent Shu, the god of air. A set of lions, perhaps depicting Ruty, the guardians of the horizon, adorn the base. Tutankhamun’s other headrests include examples made of wood, and also a blue glass exemplar adorned with gilding. In addition to the full-scale headrests, amongst the many protective amulets adorning the king’s mummy was a small iron amulet in the form of a headrest, placed beneath his head. This type of amulet became common in non-royal burials in the Late Period (664-332 BCE); before that, however, it seems the headrest amulet was reserved only for royal burials. Glencairn has an example of one of these later non-royal headrest amulets (Figure 12), which are often crafted of a dark stone.

Figure 13: Headrests were often decorated with images of protective deities like Bes and Taweret. This limestone headrest from the British Museum (EA63783) bears images of the god Bes. The hieroglyphic inscription running down the center identifies the owner of the headrest, a man named Qeniherkhepeshef who lived in the village of Deir el Medina during Egypt’s Nineteenth Dynasty (ca. 1200 BCE). Image courtesy of The British Museum.

Figure 14: Ivory headrest with support carved in the shape of the tyet, or Isis knot, from the British Museum (EA30727). Image courtesy of The British Museum.

Even headrests that are not as explicit in their decoration as Tutankhamun’s example were often decorated with protective imagery. A common engraved or incised motif on headrests is an image of the god Bes (as is noted on the chair of Hatnefer referenced above). Bes was a protective deity whose role involved the protection of the home, mothers and children, and sleeping people. He was an apotropaic force whose fearsome looks drove away evil. A sleeping person is a particularly vulnerable individual, and the Egyptians hoped that images of Bes would offer defense against nighttime evils (Figure 13). Other popular protective imagery found on headrests includes images of the equally fearsome looking goddess Taweret, and the Isis knot, also known as the tyet (Figure 14). Protection of the head and a connection with the headrest is also seen in various funerary spells. Funerary texts known as the Coffin Texts and the Book of the Dead are comprised of hundreds of magical spells designed to help the deceased make a successful passage into the afterlife. A handful of these spells make explicit reference to the headrest and compare it with the sun’s rising in the horizon. Coffin Text 232 reads: “A spell for the head-rest. May your head be raised, may your brow be made to live, may you speak for your own body, may you be a god, may you always be a god” (Translation from R. O. Faulkner). Book of the Dead spell 166 states that it is a “Spell for a headrest (to be put under the head of Osiris N.). Doves awake thee from sleep; they alert thee to the horizon. Raise thyself, (for) thou dost triumph over what was done against thee. Ptah has over-thrown thy enemies. It has been commanded to act against him who acted against thee. Thou art Horus the son of Hathor, the (fiery) Cobra (of) the (fiery) Cobra group, to whom a head was given after it was cut off. Thy head cannot be taken from thee hereafter; thy head can never be taken from (thee).” (Translation from T. G. Allen).

Figure 15: Limestone figure of a woman sleeping on her left side, her head supported by a headrest. In the collection of Glencairn Museum (E1219).

Figure 16: Closeup of the headrest on Glencairn's limestone figure (E1219).

In addition to actual headrests, amulets depicting them, and magical spells mentioning them, we also see images of headrests in use. A nice example is the small limestone figurine in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian collection (Figures 15 and 16; E1219). Here a woman is shown lying on a low bed. She rests on her proper left side and her head is supported by a headrest. Her left arm is crossed below her breast while her right arm lays straight along her side. She wears a short curled hairstyle and a long dress with a fringed hem. Her bare feet rest against the footboard of the bed. Curiously, the exterior of the footboard is decorated with two sleeping cats (for information about cats in ancient Egypt see Glencairn Museum News no. 7, 2015).

Figure 17: Similar limestone figures in the collection of Penn Museum (top, UPMAA 29-75-429) and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York (Rogers Fund, 1915, 15.2.8). Images courtesy of The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC. Note that the Egyptian bed did not have a headboard, but rather a footboard at the end of the bed.

Similar figurines of women on beds are known in other Egyptian collections. The Penn Museum has a limestone example which was excavated at the site of Memphis (Mit Rahineh). Another one can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Both the Penn example and the Met’s figurine (Figure 17) have been dated to the New Kingdom, Dynasty 18 (1539-1292 BCE). Similar figures are known from later periods in Egyptian history. They share iconography with the bed figurines—similar hairstyles, dress and arm positions—but have a more plaque-like shape.

Figure 18: Pillowcases decorated with an image of an ancient Egyptian headrest.

Figure 19: Dr. Kevin Cahail at work crafting the replica of the Penn Museum headrest (UPMAA 29-86-400a, b).

Figure 20: The finished replica headrest (in front) beside the original (UPMAA 29-86-400a, b).

Figure 21: The replica headrest made by Dr. Kevin Cahail features apotropaic images of the goddess Tawaret and the god Bes.

With all that being said, one may still wonder, just how comfortable is it to rest while using a headrest? This author tried taking the easy route by first sleeping on a modern pillow decorated with an image of a headrest (Figure 18). I can report that this use of a headrest is very comfortable, but not exactly historically accurate. Next, in an attempt to carry out some experimental archaeology, my colleague at the Penn Museum, Dr. Kevin Cahail, created a 1:1 replica of one of the headrests in the Penn Museum’s collection (29-86-400a,b) for me to use (Figures 19-21).

Figure 22: The author lying on her side, using the reproduction headrest.

Figure 23: The author found that a variety of positions can be used to comfortably support the head (but not the neck) using the reproduction headrest.

This experiment clarified a few things for me. Firstly, I had always assumed that the curved support of the headrest could be used to support either the head or the neck. This was an incorrect assumption. The headrest can only be used to support the head, not the neck. Trying to use the headrest on one’s neck was an uncomfortable impossibility. (There is a reason it is called a head-rest.) Secondly, the headrest—when positioned correctly on the head—can be used fairly comfortably while resting on one’s back. Many representations of the headrest in use (such as the Glencairn figurine) show the sleeper resting on their side. Again, it was possible to position the headrest in such a way just above one’s ear that this pose was also not completely uncomfortable. (I can also let any stomach-sleepers know that using a headrest and trying to position it on the forehead while facing downwards is impossible…) There seems to be some evidence that the headrests in ancient Egypt were padded or wrapped with linen when used. I would imagine this would make the headrest even more comfortable. As enlightening as this experiment was, I do not think I will trade in my trusty pillow for a wooden headrest any time soon!

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Associate Curator, Egyptian Section

Penn Museum

Special thanks to Dr. Kevin Cahail, an Egyptologist at the Penn Museum, for carving the reproduction of an Egyptian headrest for the purposes of this article.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.