Glencairn Museum News | Number 3, 2019

Video interview with Dr. Michael Cothren, Glencairn’s Consultative Curator of Medieval Stained Glass, about the thirteenth-century Seven Sleepers panels from Rouen Cathedral in France.

Figure 1: Three panels of stained glass from the cathedral of Rouen, purchased by Raymond Pitcairn at the sale of the Henry C. Lawrence Collection in 1921. Glencairn Museum, 03.SG.49 (left), Glencairn Museum, 03.SG.51 (center), Glencairn Museum, 03.SG.52 (right).

Long before he began in earnest to collect medieval stained glass himself, Raymond Pitcairn (1885-1966) had particularly admired three fragmentary, reworked, but still extraordinary thirteenth-century panels (Figure 1) in the New York City collection of his friend Henry C. Lawrence (1859-1919), Governor of the New York Stock Exchange. Lawrence had purchased the panels in 1918 from the Parisian dealers Bacri Frères, and they were soon installed in his townhouse at 166 W. 88th Street (Figure 2). Starting in 1915, during the early years of the project to create windows for Bryn Athyn Cathedral, Pitcairn had been taking stained-glass artists—whom he organized as a local workshop to create those windows—on “field trips” to New York. They traveled to examine excellent examples of medieval stained glass that would help them in their quest to create new works that Pitcairn hoped would match the artistic standards of great examples from the past. In addition to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Lawrence’s house was one of the stops they would make in the city so that the Bryn Athyn glass painters could study masterpieces such as these three panels in his renowned collection.1

Figure 2: Mary Shepard discovered this photograph taken in Henry C. Lawrence’s New York townhouse c. 1919, with a panel (03.SG.51; center) in Figure 1 installed in a light box for display. (The panel at the right edge of the photograph was also bought by Pitcairn at the Lawrence sale [Glencairn Museum, 03.SG.23]). Photograph now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Watson Library, “The Lawrence Collection.” I am very grateful to Dr. Shepard for allowing me to use this photograph here.

Bringing the Panels to Bryn Athyn

Given this history, it makes sense that Pitcairn would want to purchase some of Lawrence’s stained-glass panels when his collection was sold at auction over three days—January 27-29, 1921—at the American Art Association in New York. Pitcairn’s success at the sale of Lawrence’s stained glass was a defining moment of his life as a collector, perhaps the defining moment. He wrote a fairly full account of his experience at the sale in an eleven-page letter to Winfred Hyatt (1891-1959), dated at the beginning to January 21, 1921, but clearly written over a period that extended into early February. Much of the letter documents a series of cables in which Pitcairn asks Hyatt to travel to Paris to scout out potential stained-glass acquisitions from Parisian dealers.2 Although the scheme to buy things failed, the plan had been to grab stained-glass panels from these dealers before news of the prices paid at the Lawrence Sale had crossed the Atlantic. As Pitcairn said to Hyatt in the letter, “I felt it in my bones that the Lawrence sale would establish new values for 13th century glass.” His own bidding would be instrumental in making that happen.

According to the story told in Pitcairn’s letter, “Some days before the sale” he had traveled to New York and visited a Mr. Soldwedel, whom Pitcairn describes as a young architect formerly with McKim, Mead, and White. Soldwedel had gone into the “antiques business” to increase his income and had facilitated Pitcairn’s purchase from Grosvenor Thomas of the first panel of medieval stained glass he acquired.3 Pitcairn learned from Soldwedel that other wealthy collectors were interested in acquiring panels from the Lawrence collection, and that Soldwedel would be bidding for them at the auction. He offered to bid for Pitcairn as well, but Pitcairn declined: “I did not know him well enough, and in any case I feared that while we should refrain from bidding upon agreed panels [wanted by other clients of Soldwedel], some third party would walk off with the prize; and of course I did not want him to bid for me.” On this same trip to New York, Pitcairn also stopped at the Metropolitan Museum to ask what they had recently paid for stained glass, but he did not get much information there. Clearly the goal of Pitcairn’s trip was to educate himself about what the panels in the Lawrence Collection might be worth so he would be better prepared when he returned to bid on them.

“A few days later,” Pitcairn returned to New York to view the panels from the Lawrence collection that were exhibited at the galleries of “the auctioneers,” the American Art Association. In his letter he praised the quality of the exhibition: “All but a few of the panels of the glass were illuminated by electric light and most of them looked remarkably well.” He noted that because the Lawrence sale had been well advertised, many people had come to see the exhibition. He also reported that he “heard one gentleman remark that he felt as if he were in the Cluny Museum.” At this point in his letter, Pitcairn repeated how important he thought the sale would be, claiming again that it would “set a new standard in values of Gothic art, although I never dreamed that anything like the prices for which things sold would be realized.”4

On the morning of the sale, Raymond Pitcairn and Neil Acton (Kesniel C. Acton, 1895-1970, employee and eventually director of the Pitcairn Company)—who was to do the actual bidding for Pitcairn in all but a few cases—boarded an 8:00 am express train from Elkins Park to New York City. Newlin Brown (employee of the Pitcairn Company) was already on the train before them because Pitcairn “wanted an additional witness.” Brown had already looked at the catalogue with Pitcairn’s target prices in the margins and predicted that “there should be no difficulty in bidding them in, for the public would want something pretty at such a figure.” They arrived at the gallery in time for the scheduled start of the auction at 2:00 pm, but the sale began 30-45 minutes late. After telling Hyatt about the first few items he purchased, Pitcairn’s letter summarizes the mood and results: “things got more and more tense, the room was crowded, and everything I purchased after the [early] lots I mentioned was at a price higher than I expected to go.” Pitcairn was home in Bryn Athyn by 9:30 pm, where he visited his wife Mildred and baby Bethel while sharing with them the news of his success.

The provenance and subject matter of the four famous panels from the Lawrence Collection, three of which are the subject of this article, are introduced in the sales catalogue with a paragraph entitled ”’Seven Sleepers’ Series”:

”This series of four panels was removed many years ago, from a Cathedral Church in France. They are concerned with the legend of ’The Seven Sleepers of Ephesus,’ and formed the inspiration for Mr. A Kingsley Porter’s drama, ’The Seven Who Slept’, published [in 1919] by Marshall Jones of Boston.”5

The identity of the cathedral in question, as well as the relationship of the subject to the particular site, were only discovered gradually over the course of the twentieth century. The art historical detective story begins at the Norman cathedral of Rouen, long before Raymond Pitcairn’s successful bidding at the Lawrence Sale.6

Early Gothic Stained Glass at Rouen Cathedral

The cathedral church of the Norman capital of Rouen (about 80 miles northwest of Paris) was reconstructed in the fashionable Gothic style after a fire in 1200 devastated the previous Romanesque church on the site.7 The early campaigns of construction included the aisle walls of the nave, with stained-glass windows painted by some of the most important artists of the time. Stained glass was the major medium of painting in this period, and the Gothic builders of the new church reserved vast open spaces for windows between structural supports so that walls could be replaced with broad curtains of colored glass depicting sacred subjects with theological, hagiographic, moralizing, even political significance. These radiant pictures, painted with filtered light, were meant to take our breath away, to dominate our experience of a soaring, unified architectural space, to imbue us as they imbued that space with a sense of wonder and excitement. But the original windows of many Gothic churches have not maintained their original appearance. The ravages of time and changes in fashion have constructed barriers between us and most Gothic glazings by reducing them to a shadow of their original appearance. This was the case at Rouen.

Some of the stained glass for the nave aisle of Rouen was painted by one of the greatest artists of the early thirteenth century, a true old master (Figure 3). He was a virtuoso in the subtle but skillful use of overlapping to suggest three-dimensional form and space, while at the same time maintaining a strong sense of surface pattern. He enveloped his figures in lusciously painted drapery that falls in elegant, long curves over sophisticated and gracefully expressive poses. He used glass of unusually rich texture and color. He infused his figures with a variety of expressive modes through the careful manipulation of conventional facial types. Only our ignorance of his name has prevented him from holding the revered place he deserves within the history of art. Medievalists refer to him as the John the Baptist Master, naming him after his best-known works—panels from a John the Baptist Window in the nave aisle of Rouen (Figure 4);8 it would be like calling Michelangelo the Sistine Ceiling Master.

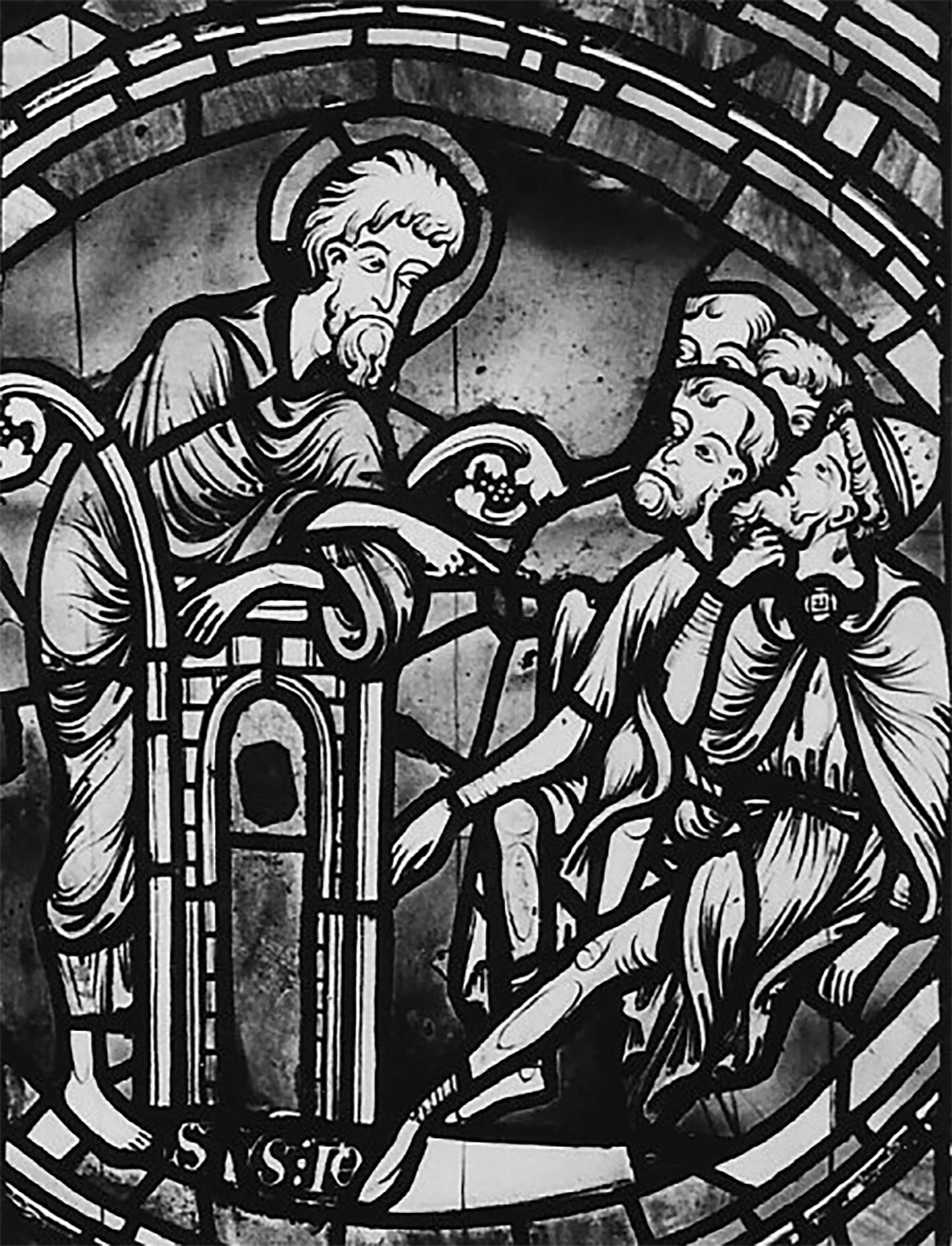

Figure 3: Details of center panel in Figure 1 (03.SG.51).

Figure 4: Saint John the Baptist preaching, a panel from a John the Baptist window of the nave aisle at Rouen Cathedral, now installed among other reused panels in the “Belle Verriére” of a nave chapel illustrated in Figure 5. This is the best-known work of the John the Baptist Master, whose workshop also painted the Seven Sleepers window.

The work of the John the Baptist Master and his contemporaries in the nave of Rouen is not well preserved. No whole windows survive on site; important panels have been removed from Rouen. In fact, some of the best-preserved examples of the work of the John the Baptist Master are in American Collections—including the two exquisite scenes from a Seven Sleepers of Ephesus window that Raymond Pitcairn acquired from the Lawrence Sale and another panel from the Lawrence sale now in the Worcester Art Museum. Only a collection of tattered fragments from this window survives in Rouen. Understanding these historical circumstances and reconstructing—at least partially—the subject and design of the original window is not easy.

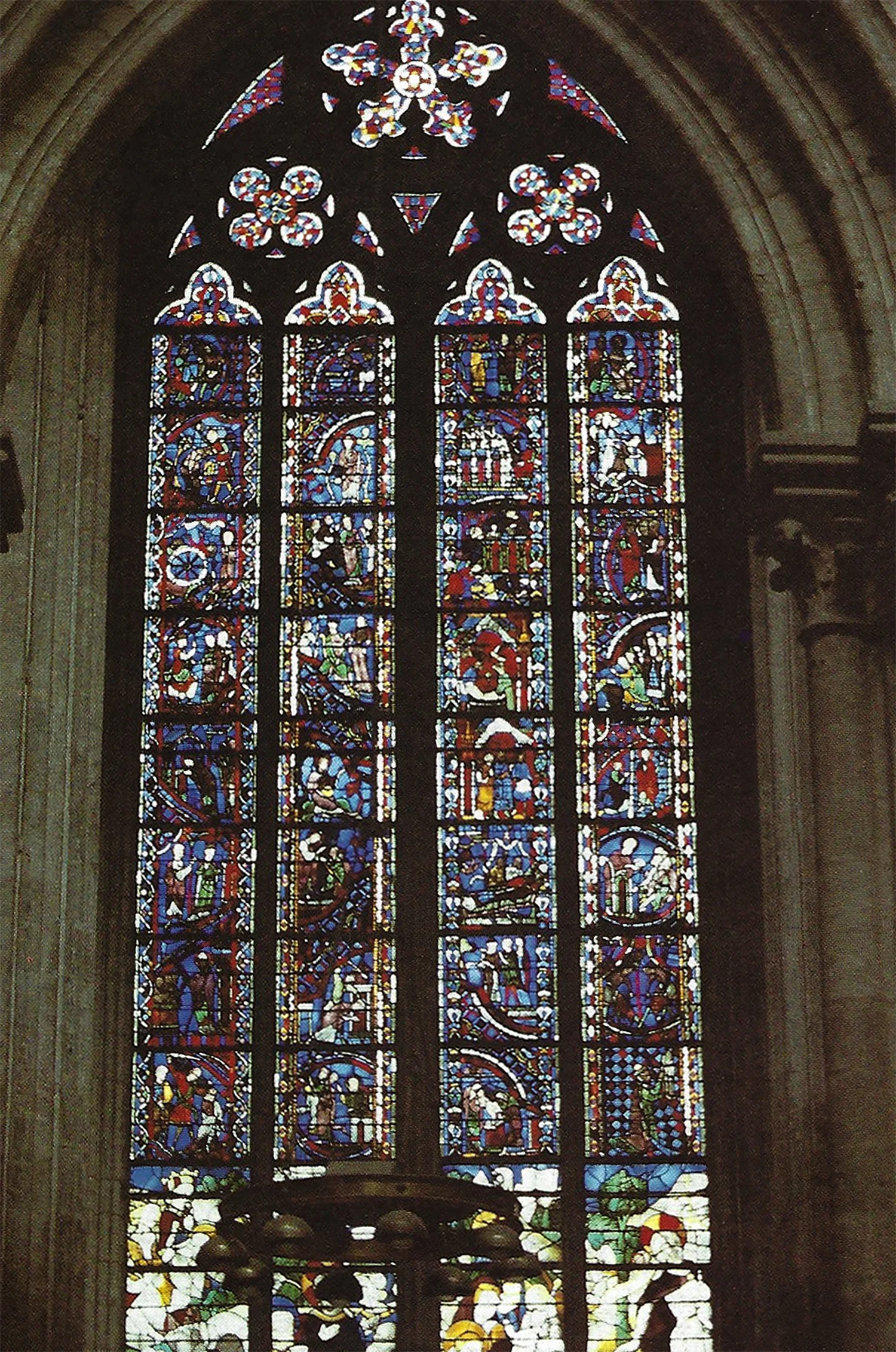

Figure 5: View of “Belle Verrière” in the chapel of Saint-Jean-de-la-nef at Rouen Cathedral. Many of the panels installed in the upper lancets originate from the broad early thirteenth-century windows of the nave aisle.

The first obstacle to understanding the early thirteenth-century nave aisle windows at Rouen occurred in the late thirteenth century. In the original design of the church, a continuous wall without chapels ran along the nave aisles. By the 1270s, however, the liturgical demands placed on this building had changed. There were not enough altars to meet the demand for services, so the aisle walls that had held the original windows were knocked down, and a series of pocket chapels were built along both sides of the cathedral between the exterior buttresses, each with an altar where Mass could be celebrated. Architectural styles changed rapidly during the thirteenth century, and the designs of the original aisle windows were old-fashioned by the 1270s. Those who designed the additional chapels replaced the broad early thirteenth-century lancets with up-to-date larger windows greatly subdivided with tracery. Instead of one broad opening, the new windows were composed of four slender ones (Figure 5).

The early stained glass was not discarded, but the panels reused in the new chapel windows were much transformed to fit their new home. Some were trimmed down, most were reshaped, turned on the bias, or patched up. Then they were plugged into the openings like a series of patches in a crazy quilt. A new, continuous strip of decoration added along the edges as a border is all that binds these battered relics into a coherent whole. There was even less concern for continuity of narrative or symbolic meaning. Episodes from the lives of various saints from several windows were randomly arranged within single lancets as if subject were a matter of little significance. It is impossible to follow a story or discern a theme. Two such patchwork windows—known as the “Belles Verrières”—confront visitors to Rouen Cathedral today in two chapels along the north aisle of the nave.9 Together they contain the remnants of a dozen or so early windows.10 As late as 1830, there were two comparable windows in south nave aisle chapels.11 Their disappearance represents the first step in a journey that would lead some of this glass to Glencairn.

During the nineteenth century, the disorder of these hodge-podge windows became uncomfortably jarring in appearance. By the middle of the century, a decision was made to replace these distracting and embarrassing ensembles with modern neo-Gothic windows that would simulate the appearance of windows from the time when the chapels were built.12 While the tidier new windows were being created, the displaced windows containing remains from the early Gothic nave aisle windows were moved for safekeeping to a first-floor room in the cathedral’s northwest tower, the Tour Saint-Romain. For the second time, remains of the original glazing had been spared during a process of remodeling or renovation, but from this new, not-so-safe dépôt panels began to leave for the art market. As we know, four entered the Lawrence collection in 1918, eventually to end up at Glencairn and the Worcester Art Museum. These panels had already left Rouen by 1911, when an inventory of the tower storeroom made by renowned French specialist in stained glass Jean Lafond (1888-1975) reported many losses. In 1932, when Lafond returned to the storeroom to choose panels for an exhibition, other panels had been smuggled out and sold, including two eventually purchased by Pitcairn, one of which is now in The Cloisters Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. During Lafond’s visit, he also discovered that the remaining panels in the crates of the storage room had not been well cared for. They were in deplorable condition, and eventually these battered fragments were moved to the French national storage facility at the Chateau of Champs-sur-Marne. During the 1980s, French glass painter Sylvie Gaudin set the fragments within a new stained-glass “reliquary” window for a choir chapel at Rouen. She surrounded the battered remains of original panels with skillful and judicious modern variations on their medieval ornamental themes—a mixture of the medieval and the modern created in such a way that respect has been shown to both.

Seven Sleepers

Reconstructing and interpreting the Seven Sleepers window from Rouen that once filled a lancet window along the nave aisle of the new cathedral church requires some serious art historical detective work. Because of my own interest in, and curiosity about, the panels at Glencairn, I decided to take on this task during the 1980s. The first order of business was examining the panels from the tower storeroom that are now in American collections, not only at Glencairn, but also at the Worcester Art Museum in Massachusetts and The Cloisters in New York. I followed up these examinations with research in Paris in 1982, during a sabbatical granted by Swarthmore College with additional financial support from the National Endowment for the Humanities. My goal was to examine the fragmentary remains that Lafond found in the crates of the storeroom in 1932, which were at that time kept in storage at the Atelier Gaudin, awaiting integration into Sylvie Gaudin’s new window. An anxious few months of negotiations were required before I received permission to examine the glass in France, at that time under the jurisdiction of the French Ministry of Culture. I was fortunate to be supported in this process by my dear friend and colleague, Catherine Brisac (1935-1991), an art historian who was a research specialist in stained glass for the Ministry. With her help, I was able to convince government officials that I could advise them on what should be done with the fragments—in some cases individual pieces of glass that had fallen from the battered panels while they were in storage. Ultimately, the Ministry of Culture allowed me to study the fragments and battered panels in return for my promise to write up a detailed inventory.13

Like any good detective, with all this physical evidence gathered, I now had to interpret it. The first step was to determine the original overall design of the Seven Sleepers window and the arrangement of the remaining panels within it. There are eleven panels or fragmentary panels, and numerous individual pieces of glass to work with, but the evidence was hardly straightforward. Many panels have been marred by later restorations (starting in the 1270s) that mask their original appearance. These later additions must be “eliminated” and occasionally the authentic cores must be “rearranged” in order to unravel the tangled knots of the later transformations that now hold these panels together. Once this was accomplished, a pattern began to emerge, revealing the original design of the panels that composed the window. By arranging these panels in groups of four, the design module for the entire window became clear. It seems to have presented a stacked series of undulating medallion shapes formed by the clustered combination of four panels (Figure 6). Those portions of the quadrants that held the figural compositions were defined by three straight sides and a fourth delineated by an asymmetrically disposed curve. Foliate ornament filled the interstices cut by the curving fillets to complete the rectangle, and a triangle of ornament formed one corner of each panel. When the panels were combined in groups of four, these triangles formed a canted square boss that served as an ornamental clasp at the center of the grouping, binding the clustered design of each medallion. No complete panel exists from the Seven Sleepers window, but each surviving fragment is compatible with this design system.

Figure 6: A reconstruction of three registers of the Seven Sleepers window, giving a sense of its overall design and showing the placement within it of the four panels from the window that are now in American collections.

A revealing test of this design reconstruction was determining the compatibility of the arrangement of extant panels and fragments with the temporal sequence of the legend of the Seven Sleepers, an episode of which is portrayed in each panel.14 First a brief summary of the story:

The story of the Seven Sleepers takes place during a turbulent period of Christian persecution under the Roman emperor Decius, when seven nobles in his court were converted to Christianity while the emperor was in Ephesus. To escape the emperor’s retribution, these new converts sought refuge in a cave outside the city. One of them, Malchus, was chosen to sneak regularly into Ephesus to buy food and listen for news of Decius’s persecutions. Later, when the Imperial court returned to Ephesus and learned of the continuing Christian piety of the seven, they prayed to God for protection. Their prayer was answered when they were put into a deep sleep, just as Decius’s soldiers closed the opening to their cave with huge stones to seal their fate as martyrs. As the years passed, the existence of the cave was forgotten, and the seven continued their sleep uninterrupted for almost two centuries. One day during the reign of the Christian emperor Theodosius II, a shepherd, seeking building stones, unknowingly uncovered the mouth of the cave, awakening the Seven Sleepers. Malchus, as if getting up from a single night’s slumber, departed for his daily search for provisions and food. Ephesus, now a Christian city, was much transformed. When he tried to buy food with what was then an antique coin minted under Decius, Malchus was led before the bishop and proconsul because the Ephesian merchant was suspicious. Upon hearing his story, both sacred and secular authorities followed Malchus to the cave to witness the survival of his six companions, and the astonished bishop and proconsul sent messengers to inform the emperor of what had transpired. Theodosius traveled to Ephesus to venerate the Seven, who, after talking to him, fell once more into sleep.

With this story in mind, the scenes portrayed in surviving panels from the Seven Sleepers window can be arranged in chronological narrative order within the design format of the window based on an analysis of their shapes and framework. The three registers containing the “American panels” can be used as examples (Figure 6).

Two scenes that survive at Glencairn are from what was probably the seventh register, numbering from the base of the window (Figure 6, bottom). To the left, Malchus is seized as he attempts to buy bread with antique money from a baker (Figure 7), and at right, he is brought before the bishop and proconsul and accused of possessing it (Figure 8). This second panel is one of only two that have retained the inscriptions that once identified the subjects of scenes in the window—“Hic ante presvlem dvcitvr” (“Here he is led before the proconsul”). The left panel of the register above this one shows messengers arriving to share the news of the miracle with the emperor Theodosius. It was purchased by the Worcester Art Museum at the Lawrence sale. I have placed the surviving strip of another panel to the right on this register to help round out the medallion design with information about the ornamental, canted-square boss that bound each four-panel medallion at the center, but its truncated composition is too general to associate it with any particular episode in the story. On the next register up, however, the scene of Theodosius on horseback traveling to venerate the Seven fits conveniently at the left as a subsequent moment in the unfolding narrative, the first episode in what was probably the last medallion in the story.15

Figure 7: Malchus is seized while trying to buy bread with an antique coin, from the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus window of the nave aisle of Rouen Cathedral, c. 1200-1203, now in Glencairn Museum (03.SG.49).

Figure 8: Malchus is led before the bishop and prefect (“hic ante presulum ducitur”), from the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus window of the nave aisle of Rouen Cathedral, c. 1200-1203, now in Glencairn Museum (03.SG.51).

The subject of this window is extraordinarily unusual. Rouen represents the only instance of the use of the legend in Gothic stained glass, and the only extended visual narrative cycle that survives from the Middle Ages in any medium. The story was more popular in England than in France, and that information introduces an important aspect of the window’s potential meaning in Rouen, at the same time as it provides rare extra-stylistic evidence for dating it. In England, the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus were not only popular; they were charged with special royal significance.16 While at dinner one Easter, king Edward the Confessor was said to have had a vision of the Seven turning over in their sleep. This curious anecdote found its way into his biographies by the twelfth century, and after his canonization in 1161, it became associated with the royal cult. Thus, it would be logical to consider if this window might be connected with England and its royal saint. Historical circumstances make such a connection likely.

In April 1199, English king Richard Lionheart died of battle wounds, and John, his brother, became both king of England and duke of Normandy. John did not hold his continental domain long. After a military victory, French king Philip Augustus marched into the cathedral of Rouen in July of 1204 and claimed Normandy for himself. Under these circumstances, the installation of a window depicting a very unusual subject that was charged with English royal associations, seems highly unlikely after 1204 when the political allegiances of Normandy turned from England to France. And if the window needs to pre-date 1204, it also must post-date 1200, the date of the fire that led to the reconstructed cathedral for which the stained glass was created. In fact, the historical record indicates that king John promised a generous donation to the building campaign, and he fulfilled this pledge between 1200 and 1203. In 1202, when he was in Rouen, John authorized fundraising for the reconstruction, while expressing his special affection for the cathedral because it contained the tombs of his ancestors.17 The dynastic significance he attributed to the building would only have been enhanced by a reference through the Seven Sleepers window to the life of his sainted predecessor, Edward the Confessor, whose mother, Emma, was Norman. All these factors suggest that the Seven Sleepers window was created between 1200 and 1203, a date completely consistent with its classicizing style.18 Such precision in dating is rare in the study of medieval art.

Seven Kneelers

Some readers will have noticed that the third panel from the Lawrence Collection that appears at the beginning of this article has not figured into a discussion of the Seven Sleepers window even though it has traditionally been associated with it (Figure 9). Both the subject matter—seven kneeling figures, four represented by whole heads and their three overlapped companions implied by slivers of their heads peeking out above the other four—and the fact that this panel traveled from Rouen into the Lawrence Collection in the company of three Seven Sleepers panels (two now at Glencairn and a third in Worcester) seems to qualify it for inclusion in the window we have just explored. There are several reasons for rejecting such a seemingly logical conclusion.

Figure 9: Seven Kneelers (probably apostles), from the John the Evangelist window of Rouen Cathedral, c. 1240-1245, now in Glencairn Museum (03.SG.52).

Figure 10: Scene from the John the Evangelist window of Rouen Cathedral, c. 1240-1245, now installed in the “Belle Verriére” of the Chapel of Saint-Jean-de-la-nef in Figure 5.

The physical character and color of the glass is different from that used in the Seven Sleepers panels—blues are more saturated, reds more brilliant. Differences in painting style are equally striking. The mannered, wiry, and dry articulations of the distorted heads of the kneelers makes them almost the antithesis of the fluidly painted and plastically conceived faces of the Sleepers. The draped bodies of the kneelers seem schematic and flat when compared with suavely delineated, heavy drapery, which emphasizes the volumetric qualities of the Sleepers. But the panel with the seven kneelers does come from the cathedral of Rouen. It finds a close stylistic analogue in a panel still installed in one of the “Belles Verrières” in a north nave chapel (Figure 10). There are strong stylistic parallels between the figures—noticeable in drapery, hands, gestures, and faces. Once the Glencairn panel is reduced to its figural core (which had been surrounded by extraneous glass to form it into a marketable rectangle), the shape of the panel coordinates with the panel now in Rouen, and if three related fragments from Rouen (now in storage at the Chateau of Champs-sur-Marne but once in storage crates from the tower room where the Seven Sleepers panels were once kept) are added to the group, a reconstruction of the design of the original window that held all of them can be created (Figure 11). The panel at the top left of this partial reconstruction carries the key to the subject of the original window. The scene portrayed is the distinctive death of John the Evangelist, who having been informed by Christ that the end of his life was near, took his final communion and, as he was consumed by a blinding light, voluntarily climbed into his tomb prepared to die.19 The seven kneelers came from a John the Evangelist window at Rouen.

Figure 11: Reconstruction of the upper four registers of the John Evangelist window of Rouen Cathedral, including the figural core of the panel in Figure 9.

Unlike the Seven Sleepers window, this St. John the Evangelist window was not part of the early thirteenth-century glazing campaign that produced the Seven Sleepers window and the stylistically related St. John the Baptist window. The style of these kneelers situates their window a few decades later into the thirteenth century, when the same artists produced a Good Samaritan window for the choir ambulatory at Rouen, probably during the 1240s.20

They also seem to have created a window portraying the life of a bishop saint for the Virgin Chapel of the nearby Cathedral of Beauvais, probably around 1245.21

Stylistic features these windows have in common include facial types, gestures, postures, and figural proportions. Environments are as closely related as figures. Instead of the volumetric classicism characterizing the panels from the Seven Sleepers window, these painters from the 1240s preferred more flattened silhouettes and wiry, rapid, summary painted articulation.22

Among Raymond Pitcairn’s purchases at the sale of the Lawrence Collection in 1921 were some of the most important panels of French Gothic stained glass that he would acquire. Perhaps the most famous is the king from the axial Jesse Tree window of the clerestory glazing at Soissons Cathedral (Figure 12), a work he so admired that he took it home with him directly from the sale, an event described in his letter to Winfred Hyatt: “At the end of the sale I went to the auctioneers and asked for the King which Newlin Brown and I took in a taxicab to the Pennsylvania Depot—tempo that of a funeral.”

Figure 12: King from a Jesse Tree window, from the axial clerestory window of Soissons Cathedral, c. 1210-1225, now in Glencairn Museum (03.SG.229).

But the three panels considered here, even if there may not have been room for them in the taxi, are just as special. Although described in the sale catalogue as coming from a Seven Sleepers window from an unspecified cathedral in France, not all three originate from a window of that subject. Together, however, they present a richer collection of Gothic stained glass than Raymond Pitcairn realized, rare survivors of two windows from the Norman cathedral of Rouen. Two of them do in fact portray scenes from the legend of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, and they were painted by the John the Baptist Master, one of the greatest early Gothic glass painters. His window was important; it may have been funded directly by King John of England between 1200 and 1203. The third panel contains a well-preserved figural group from a Saint John the Evangelist window created by artists working a generation later during the 1240s. As a group, these three panels allow us to evaluate the stylistic evolution of stained glass over the first half of the thirteenth century—from the expressively classicizing Sleepers to the edgy mannerist Kneelers—at one of the most important Gothic cathedrals in France.23 At the same time, the story of their acquisition documented in one of Raymond Pitcairn’s longest letters, provides a tantalizing insight into his own development as a collector.

Michael W. Cothren, PhD

Consultative Curator of Medieval Stained Glass, Glencairn Museum

Scheuer Family Professor Emeritus of Humanities, Swarthmore College

Endnotes

1 Both Henry C Lawrence and Raymond Pitcairn are discussed as collectors of medieval stained glass in Shepard, “Out of Context.”

2 Raymond Pitcairn kept carbon copies of the typed letters he sent out, and these copies were bound into books identified by year. The copy books are now in the Glencairn Museum Archives, and the eleven pages of the letter to Hyatt is in the bound volume for 1921. I am grateful to Ed and Kirsten Gyllenhaal for providing me with pictures of the carbon copy of this letter.

3 03.SG.218, a panel of grisaille from the cathedral of Salisbury. See Hayward, Radiance and Reflection, pp. 229-230. For a broader discussion of Soldwedel’s work with Grosvener Thomas, see Marilyn M. Beaven, “Grosvenor Thomas and the Making of the American Market for Medieval Stained Glass,” in The Four Modes of Seeing: Approaches to Medieval Imagery in Honor of Madeline Harrison Caviness, ed. Evelyn Staudinger Lane, et al. (Ashgate, 2009), pp. 491-493.

4 At this point in Pitcairn’s letter to Hyatt, he pauses to share some very personal news, announcing the birth of a daughter (Bethel Pitcairn Junge, [1921-2008]) on January 26th, “which is more important than a dozen Lawrence collections.”

5 Collection of a Well-Known Connoisseur, just before the entries for lots 374-377.

6 For a more detailed, expansive, and well documented version of the arguments that are presented in this article, see Cothren, “The Seven Sleepers.”

7 For this fire and the architectural campaign that followed it, see Cothren, “The Seven Sleepers,” footnote 41.

8 Lafond, “La verrière des Sept Dormants,” p. 405.

9 This sobriquet applied to the reused thirteenth-century panels in later windows is believed to date to the fourteenth century, but no fourteenth-century document has ever been cited. See Beaurepaire, “Procès-verbal,” p. 246 and 254 (where he comments “On disait les Belles-Verrières dès le XIVe siècle” [They were called the Beautiful Windows since the 14th century], but gives no source for this information).

10 The best published pictures of the two Belles-Verrières in north nave chapels are in Ritter, Les vitraux, pls. I-VIII.

11 The sources for this information are discussed in Cothren, “The Seven Sleepers,” p. 220, footnote 8. The principal sources are the references in the two books by Langlois cited here in the bibliography.

12 The nineteenth-century windows were destroyed with much of the cathedral in a devastating bombing of Rouen in April 1944. Today twentieth-century stained-glass windows take their place.

13 Copies of this inventory were given in February 1983 not only to the Direction du Patrimoine of the Ministry of Culture in Paris, but also to The Cloisters and Glencairn Museum.

14 Sources for the legend of the Seven Sleepers are discussed in Cothren, “Seven Sleepers,” p. 207 and footnote 28.

15 This panel once belonged to Raymond Pitcairn, but it was given in 1980 to the Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Cloisters Collection, 1980.263.4).

16 For discussions of the history of the legend in England, see Cothren, “Seven Sleepers,” footnotes 36-39.

17 For a more detailed and fully documented discussion of this rich historical context, see Cothren, “The Seven Sleepers,” pp. 209-212.

18 For a fuller discussion of style in relation to dating, see Cothren, “The Seven Sleepers,” pp. 212-213.

19 For the identification of the subject of this panel, see Cothren, “The Seven Sleepers,” p. 214 and footnote 75.

20 Ritter, Les vitraux, pls. 21-23.

21 Cothren, Picturing the Celestial City, pp. 44-69.

22 For a more thorough assessment of the style of the Rouen John the Evangelist window and its relationship to the other windows cited here, see Cothren, “The Seven Sleepers,” pp. 216-218; and Cothren, Picturing the Celestial City, pp. 65-69.

23 A third panel at Glencairn Museum (03.SG.242) gives us an insight into a third window from the early glazing at Rouen, this one dedicated to the life of the Apostle Peter. See Cothren, “Fragments.”

Bibliography

Beaurepaire, Charles de. “Procès-verbal de la visite archiépiscopale des chapelles de la métropole [de Rouen] en 1609.” Bulletin de la commission des antiquités de la Seine-Inférieure 7 (1885-1887), pp. 243-267.

Collection of a Well-Known Connoisseur, A Noteworthy Gathering of Gothic and Other Ancient Art Collected by the Late Mr. Henry C. Lawrence of New York, 27-29 January 1921. Sale Catalogue, American Art Association, New York, 1921.

Cothren, Michael W. “The Seven Sleepers and the Seven Kneelers: Prolegomena to a Study of the ‘Belles Verrières’ of the Cathedral of Rouen.” Gesta 25 (1986): 203-226.

Cothren, Michael W. Picturing the Celestial City: The Medieval Stained Glass of Beauvais Cathedral. Princeton University Press, 2006.

Cothren, Michael W. “Fragments of an Early Thirteenth-Century St. Peter Window from the Cathedral of Rouen.” Gesta 37/2 (1998): 158-164.

Hayward, Jane, and Walter Cahn, et al. Radiance and Reflection: Medieval Art from the Raymond Pitcairn Collection. Exhibition Catalogue, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1982 (esp. pp. 149-152).

Lafond, Jean. “La verriére des Sept Dormants d’Ephese et l’ancienne vitrerie de la cathédrale de Rouen.” In The Year 1200: A Symposium. New York, 1975, 399-416.

Langlois, E. H. _Essai historique et descriptif sur la peinture sur verre ancienne et moderne, et sur les vitraux les plus remarquables de quelques monuments français et étranger_s. Rouen, 1832, pp. 29-32.

Langlois, E. H. Mémoire sur la peinture sur verre et sur quelques vitraux remarquables des églises de Rouen. Rouen, 1823, p. 12.

Ritter, Georges. Les vitraux de la cathédrale de Rouen: XIIIe, XIVe, XVe, et XVIe siècles. Cognac, 1926.

Shepard, Mary B., “Out of Context: Portraits of Private Collectors and their Medieval Stained Glass.” Forthcoming in E. Pastan and B. Kurmann-Schwarz, ed., Investigations in Medieval Stained Glass: Materials, Methods, and Expressions, Reading Medieval Sources 3. Brill, 2019.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.