Glencairn Museum News | Number 5, 2019

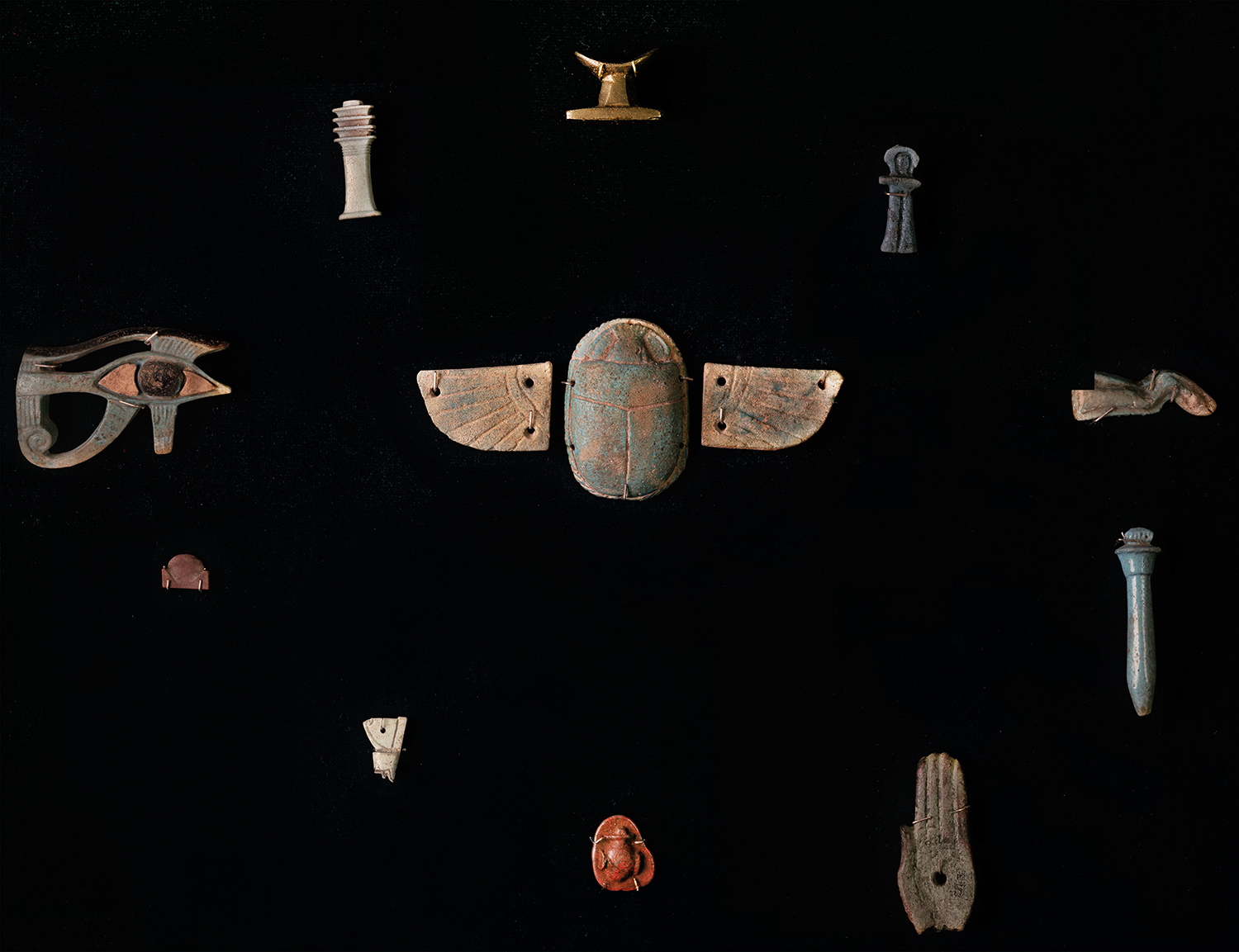

Figure 1: The Egyptians buried their dead with objects they believed would ensure a successful transition to the afterlife.

Figure 2: Some objects buried in the tomb had been used by the deceased during life, but other tomb goods like shabtis, canopic jars, and certain amulets were made specifically for the burial.

As early as 5000 BCE, during Egypt’s Predynastic Period, the Egyptians began including grave goods in burials, indicating that they believed that the deceased would have need of these objects after death. These early burials consisted of bodies wrapped in basketry or skins (without a protective coffin or body container) and placed in oval graves. Tomb goods such as objects of personal adornment, ivory and bone implements, stone palettes for grinding pigments, and pottery accompanied the burial. From these humble beginnings, the belief in an afterlife and the preparations and practices related to this idea evolved and expanded throughout pharaonic history.

Figure 3: This Predynastic mummy of a man is in the British Museum. He lived circa 3400 BCE. The exhibit is a reconstruction of a Predynastic burial, including tomb goods typical of this time period. Image courtesy of The British Museum, accession number EA32751.

Figure 4: Predynastic pottery in Glencairn’s Egyptian Gallery.

Texts tell us in the Egyptians’ own words how important preparation for burial was, and they describe what types of objects were considered necessary for a successful passage to the afterlife. One of the most important literary texts from ancient Egypt, The Tale of Sinuhe, tells the story of a man called Sinuhe who flees Egypt when he hears that something dreadful has happened to the king. Sinuhe goes into exile in the Levant and lives amongst the Bedouin, where he is taken in as an adopted son of one of the resident chiefs. He marries a local woman and lives among this group for many years, all the while missing Egypt. One day a letter from the pharaoh arrives inviting Sinuhe back from his self-imposed banishment. The king reminds Sinuhe just how important a proper Egyptian-style burial is, as he describes all of the preparations that should take place. The king writes:

“Think of the day of burial, the passing into reveredness. A night is made for you with ointments and wrappings from the hand of Tait [a goddess associated with linen and mummy wrappings]. A funeral procession is made for you on the day of burial; the mummy case is of gold, its head of lapis lazuli. The sky is above you as you lie in the hearse, oxen drawing you, musicians going before you. The dance of the mww-dancers is done at the door of your tomb; the offering-list is read to you; sacrifice is made before your offering-stone. Your tomb-pillars, made of white stone, are among those of the royal children. You shall not die abroad! Asiatics shall not inter you. You shall not be wrapped in the skin of a ram to serve as your coffin.”

With these words, we can see some of the essential features of the Egyptian funeral. The body is prepared and wrapped in linen and then placed in a coffin. The “sky” referenced in the king’s letter is Nut, the sky-goddess whose image often decorated the lids of coffins. Nut was thought to give birth to the sun each morning, and as such was a potent image for the concept of rebirth. The coffin was brought to the tomb by means of a procession of mourners and performers who would carry out ritual dances as part of the funeral. As the Egyptians believed that the deceased would continue to require nourishment in the afterlife, the text tells us that provisions are made for the deceased to receive offerings. Although this text was composed in the Middle Kingdom (circa 1980-1630 BCE), many of the preparations described above continued to be practiced throughout the rest of ancient Egyptian history.

The Egyptian pantheon consisted of hundreds of deities, each of whom was responsible for some aspect of ancient Egyptian life—from creator gods, to gods of kingship, to deities who protected the home and those who were patrons of specific professions. Many of these important deities appear on objects throughout Glencairn’s Egyptian Gallery. As we focus here on gods associated with the funerary realm, it might be best to first understand how some of these gods came into being. The creation of the world was described in several different ways in Egyptian texts. In the Heliopolitan creation myth, a sole creator god (Re-Atum) is responsible for creating the first male and female pair of deities. These first beings are Shu, the god of air, and Tefnut, the goddess of moisture. Shu and Tefnut form a pair, and in turn produce a new generation of gods: Geb, the god of the earth, and Nut, the goddess of the sky. Geb and Nut next produce four offspring: Osiris, Isis, Seth and Nephthys. Osiris and his sister Isis form a pair, as do Seth and Nephthys. Myths relate that Osiris was thought of as the first king of Egypt, a good and just ruler who brought civilization to the land. However, Osiris’ brother Seth was jealous and devised a plan to kill him. Ultimately, Seth murders and dismembers Osiris. His body parts are cast into the Nile and dispersed throughout Egypt. Isis and Nephthys retrieve them, and with the assistance of the god Anubis, they mummify him. By means of her great magical power, Isis is able to revivify Osiris, and she becomes pregnant with his son. This child is the god Horus, who takes his father’s throne as king on earth. Osiris becomes the ruler of the underworld.

Figure 5: Bronze votive statuette of Osiris (E74). The god is shown mummiform, wearing his usual crown and holding the crook and flail as symbols of his kingship.

Figure 6: Bronze votive statuette of Isis and Horus (E1164).

Let’s now look at several of the objects in the Egyptian Gallery that were made specifically for funerary purposes, and explore their use and symbolism.

One of the essential elements of a good Egyptian burial is a coffin. Coffin shapes and decoration changed considerably during the roughly 3000-year pharaonic period, but their purpose remained the same throughout. Regardless of their shape, coffins had a practical function, serving as a container for the body of the deceased, and they offered a layer of protection for the body from accidental or intentional damage. Coffins could also provide religious or magical protection as well. Decoration of the coffin’s interior and exterior could include imagery and texts designed to assist the deceased on the passage to the afterlife.

A highlight of the Egyptian Gallery at Glencairn is the beautifully preserved painted wooden coffin lid of a man named Sema-Tawy-iirdis (E1267). This name means “Sema-Tawy is the one who gave it.” Sema-Tawy means “The Uniter of the Two Lands,” and this phrase is a nickname of the god Horus, making reference to his role as a god of kingship. After the death of his father Osiris, Horus came to the throne. Each Egyptian pharaoh was a manifestation of Horus on earth, and one of the roles of the Egyptian king was to maintain the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt. (Previously, the name of the owner of this coffin was read incorrectly as Sema-iirdis. However, the hieroglyphs on the coffin lid contain a sportive writing of “Sema-Tawy.” The hieroglyph for sema (Gardiner sign list F36) is in the center and is flanked by a sedge plant on one side and a papyrus plant on the other. The papyrus represented Lower Egypt and the sedge represented Upper Egypt, thus, the “Two Lands.”)

Figure 7: The beautifully painted coffin lid of Sema-tawy-iirdis (E1267).

Figure 8: A closeup of the name of the coffin’s owner, Sema-tawy-iirdis.

This coffin likely dates to the early part of the Ptolemaic Period (305-30 BCE). It is anthropoid in shape, taking the form of a wrapped mummy with an exposed head. The deceased is shown wearing a tripartite wig and a false beard. A large broad collar (wesekh) is on his chest. The collar has many rows of multicolor floral and geometric elements, and each terminal of the collar (located on the shoulders) takes the form of a falcon head topped with a sun disk. This is a common motif on coffins of this type and actual examples of similar collars are well known.

Figure 9: The area of the chest is covered by a large multi-color wesekh collar.

Figure 10: Wesekh collars were popular pieces of jewelry in ancient Egypt, worn by both men and women. This example, comprised of faience beads, was excavated at the site of Meydum. It dates to Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (1980-1630 BCE). Image courtesy of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, accession number 31-27-303.

Figure 11: Close-up of one of the falcon-headed collar terminals on the coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis.

Below the collar is a large representation of the sky goddess Nut, who is shown with outstretched wings. She is identified by the hieroglyphs spelling her name. On either side of her head, an image of a wedjat eye appears. This protective symbol is also known as the “Eye of Horus.” A kneeling goddess decorates each side of the coffin—Nephthys appears on the proper left, and Isis is on the proper right. They wear the hieroglyphs for their names atop their heads, and their hands rest on the shen-sign, a symbol for eternity.

Figure 12: Images of goddesses with outstretched wings frequently decorate the lids of coffins. These images offered protection to the deceased. The goddess Nut is shown on the coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis.

Figure 13: Isis is shown on the proper right side of the coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis.

Figure 14: Nephthys is shown on the proper left side of the coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis.

The lower half of the coffin is decorated with two vertical columns of hieroglyphic text running down the center. This text is a type of funerary prayer called a hetep di nsw. The text reads as follows:

Figure 15: The coffin is decorated on the front with two vertical columns of hieroglyphic text containing an offering prayer and the identification of the name and parentage of the deceased.

“An offering which the king gives to Osiris, foremost of the West, the great god, Lord of Abydos, that he may give a good burial, bread, beer, beef and fowl, incense, linen, oil, and everything good and pure for the Osiris, Sema-tawy-iirdis, the son of Horwedja, born of the Lady of the House, […](?)-aset.”

The text tells us the name of Sema-tawy-iirdis’ parents. His father has a very common and well-known name, Horwedja. His mother’s name is garbled (or unusual), but the second part of her name is clear and reads “Isis/Aset.” The first hieroglyph in the name is damaged, but the traces that remain look very much like Gardiner’s sign list D40. It is possible that this is a mistake for Gardiner’s sign list D43. This would give a potential reading of “Huy(wi)-Aset” for the mother’s name, but this name is unattested elsewhere.

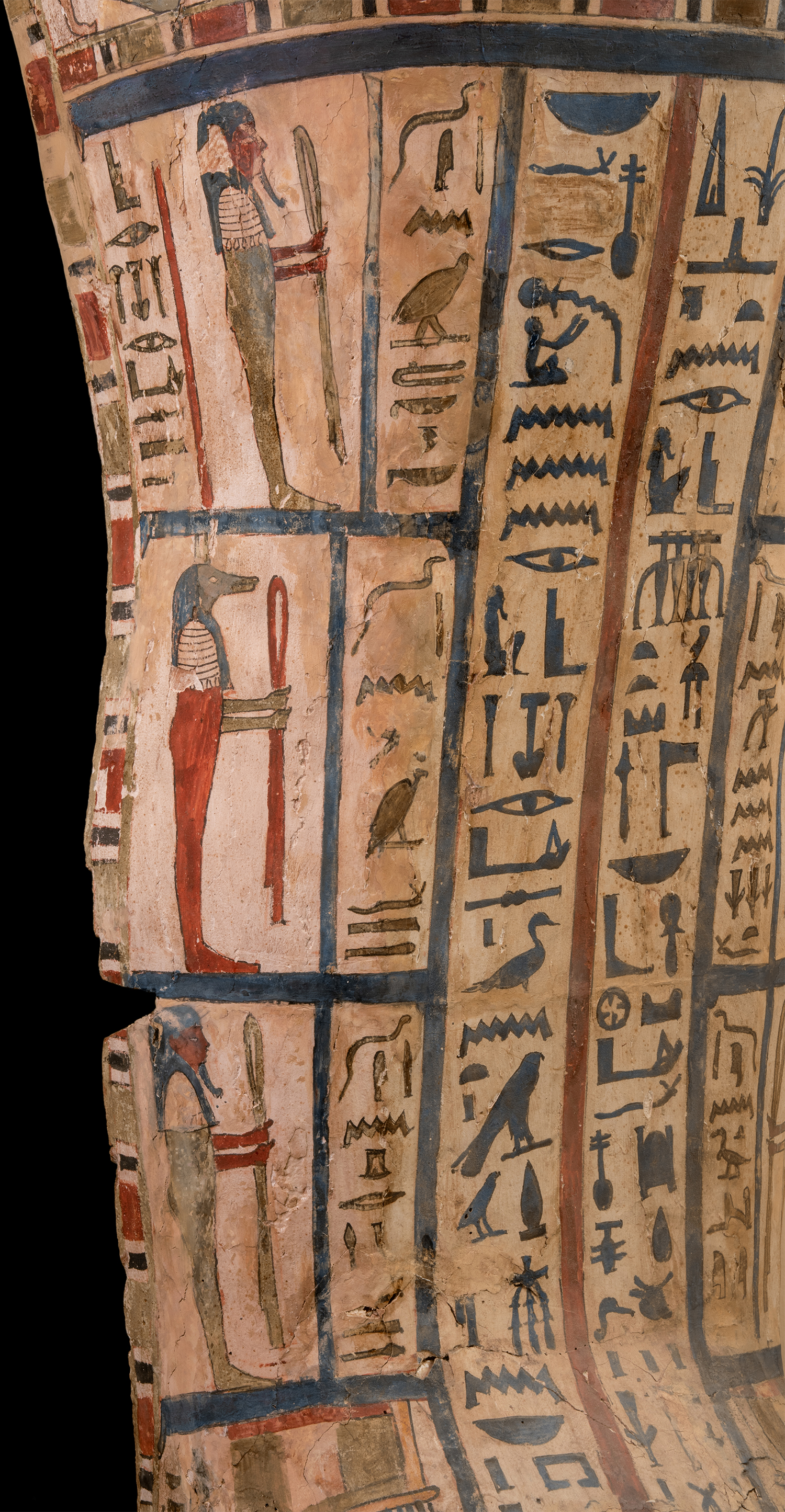

Three registers, each containing an image of a mummiform deity, flank the two columns of hieroglyphic texts. Each deity is labeled with a hieroglyphic text. The first four deities are the group known as the Sons of Horus. These gods protect the internal organs of the deceased and they frequently decorate the lids of canopic jars. The final two figures have corrupted names, but the figures are likely minor underworld deities. At the level of the feet, two jackals on shrines appear on either side of the columns of text. These jackals are identified with hieroglyphic labels reading “Anubis.” There were a number of Egyptian deities who could take the form of a jackal or jackal-headed man including Wepwawet, Khentyamentiu, Duamutef, and Anubis. The best-known of these jackal gods is the god Anubis. Anubis is often shown as a recumbent jackal atop a shine. (Representations of Anubis in this form appear on several objects in Glencairn’s Egyptian Gallery.) The bottom of the coffin consists of a small podium decorated with alternating djed pillars symbolizing stability, and ankh signs meaning “life.”

Figure 16: Funerary deities appearing top to bottom are human-headed Imsety, jackal-headed Duamutef, and a human-headed deity.

Figure 17: Funerary deities appearing top to bottom are baboon-headed Hapy, falcon-headed Qebehsenuef, and a human-headed deity.

Figure 18: Anubis in the form of a recumbent jackal appears twice on the foot of the coffin.

Figure 19: A frieze of alternating djed pillars (“stability”) and ankhs (“life”) decorate the small podium at the foot of the coffin lid.

Decorated mummy shrouds offered another layer of magical protection. These large sheets of fabric covered the linen-bandaged mummy and were illustrated with a depiction of the deceased as well as funerary and divine imagery. While complete examples are rare, fragmentary linen shrouds can also give us insight into funerary beliefs. In the Glencairn collection, there is a fragment of a linen shroud (E1115) that dates to the late Ptolemaic or Roman period. Originally this shroud would have had a close to life-size image of the deceased in the center. All that remains of the image of the deceased are his sandal-clad feet and the lower portion of his proper right leg. To his right some divine imagery remains. At the bottom of the shroud, Anubis is seen in jackal form atop a shrine. (This image and its position on the shroud is virtually identical to what we see on the coffin of Sema-Tawy-irrdis mentioned above.) Above that image is a scene of the deceased on the left, worshipping a group of four deities (Osiris, Isis, Anubis and Nephthys). Here, Anubis is shown as a man with a jackal head. It is interesting to note that there are blank columns near each of the figures which have not been filled in with text. The coffin lid of Sema-Tawy-iirdis and the linen shroud are similar in that they offered direct protection to the body due to their close physical proximity to the mummy.

Figure 20: Decorated linen shrouds are known as early as the New Kingdom (1539-1075 BCE), but most of the extant examples (like the one seen here) date to Roman Period in Egypt. The decoration on the shrouds recalls that which is found on coffins: a central figure of the deceased, with divine and protective imagery along the sides.

Another very important aspect to a good Egyptian burial was the tomb itself and the decorated architectural elements associated with its construction. As with coffins, tomb design and structure varied over time, and the size and quality of tomb decoration depended largely on the economic status of its owner. Even so, certain aspects of the tomb remained consistent. Broadly speaking, Egyptian tombs consisted of two parts—a “private” part below ground where the mummy, coffin and tomb goods were interred at the time of burial, and a “public” part above ground where the funerary cult would be carried out and where visitors could leave offerings for the deceased. This above-ground part of the tomb often took the form of a decorated chapel, which could range from a small single room to a massive multi-chambered building. What all of these tomb chapels share is the goal of commemorating the deceased in texts and images (in the form of wall reliefs and stelae) and providing a location for the offerings which would be needed to sustain the deceased in the afterlife.

Dating to the Fifth Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (circa 2494–2345 BCE), the mastaba tomb of Tepemankh was built at the site of Giza. This “false door” (E1150) is one of several parts of his tomb that are housed in museums around the world. Other parts of this relief are in the Louvre, Paris (E25408) and in the Ny Carlesberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (AEIN 1438). Tepemankh was an important official who held a number of notable positions. The texts on his monument tell us that he was a royal acquaintance, an overseer of the department of palace attendants of the Great House, and a priest in the cult of King Khufu.

Figure 21: The false door relief of Tempemankh (left, E1150), on exhibit in Glencairn’s Egyptian Galley, joins to pieces in other museums. This line drawing shows the placement of the various relief fragments from Tepemankh’s tomb.

The relief takes the form of a “false door.” This is an architectural element in an Egyptian tomb that served as a magical (not actual) doorway for the ka (or life force) of the deceased. The Egyptians believed that the ka could enter and exit the false door to receive the offerings left in front of it by visitors to the tomb. The joining section of this relief, now in the Louvre Museum in Paris, contains a “menu list” of offerings. In the event that real offerings were not left by visitors to Tepemankh’s tomb, these carved representations would suffice to sustain his ka.

Figure 22: Overall view of the false door of Tepemankh from Giza.

Figure 23: A closeup of the text on the false door of Tepemankh showing the cartouche of King Khufu as part of Tepemankh’s title: hem-netcher Khufu (“Priest of Khufu”).

On the left of the relief in Glencairn, a large figure of Tepemankh is shown together with a hieroglyphic inscription giving his name and titles. Below him a much smaller figure of a priest brings an offering of meat. The central part of this relief is the false door, which is also inscribed with the titles and name of Tepemankh. On the right hand column, the name of King Khufu can be found in a cartouche as part of Tepemankh’s title of “priest of Khufu.” The center of the door includes two depictions of offering stands topped with vessels for liquid. Above the false door is a smaller scene of Tepemankh seated before a table of offerings. Part of a funerary prayer invoking the god Anubis can be seen to the right of this scene.

Liquid offerings were an important part of the funerary cult. Funerary offering prayers requested a variety of liquids including beer, wine, and cool water. Some tombs incorporated offering tables with shallow depressions for holding liquid. These would be set up in front of the false door. Alternatively, some tombs were equipped with offering basins which were meant to hold libations. A small rectangular limestone offering basin is on exhibit in the Egyptian Gallery at Glencairn. On loan from the Penn Museum (E13526), this basin is inscribed along its rim with a funerary prayer for a woman named Per-senet. The inscription tells us that she was a “royal acquaintance” and that her son, awab-priest named Rudj, dedicated this basin for her. This basin was found in the tomb of Per-Senet and her husband, a man named Iymery, at Giza.

Figure 24: Limestone offering basin of Per-senet from her tomb at Giza, in Glencairn’s Egyptian Gallery. This basin is on loan from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, accession number E13526.

Husbands and wives were often commemorated together on funerary stelae. An example of this can be seen on the limestone funerary stela (E1151) depicting a man and his wife. The pair are shown seated facing each other. In between them, a short two-column hieroglyphic inscription identifies the individuals with their names. He is identified as the “juridical inspector of scribes, Ineb,” and the text tells us that she is “his wife, his beloved, Henti.” Their tomb was located at Giza. We know from other inscriptions in the tomb that his full name is Ankhemtjenenet and that Ineb was a nickname.

Figure 25: Limestone Old Kingdom funerary stela of Ineb and Henty (E1151).

Another limestone funerary stela (E1266) in the Egyptian Gallery belongs to a man by the name of Maienhekau, who lived during the reign of pharaoh Tuthmosis III (circa 1479-1425 BCE). This king was a great warrior, and Maienhekau was also a military man. The inscription on the stela tells us that he served as a bearer of arms of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Menkhepperre (Tuthmosis III), and a standard bearer of the boat named “the Calf of Amenhotep.”

Figure 26: New Kingdom limestone funerary stela of Maienhekau (E1266).

This rectangular stela is decorated with offering prayers, representations of the deceased and his family, as well as images of several deities. At the top of the stela in the center, two recumbent jackals representing the god Anubis face each other. The text that goes around the edge of the stela is a funerary prayer. The center of the stela is divided into four horizontal registers. At the top, the deceased is shown twice, kneeling in a prayerful position before Osiris on the right and Ptah on the left. The second register shows two scenes of the deceased seated with a woman. This appears to be a representation of Maienhekau with two wives. On the left he is shown with his (second?) wife Meryt, and on the right he is shown with his wife Henuttawy. Before each image of the couples, a son is shown offering to them. (It is unclear if one wife predeceased the other. It was uncommon for non-royal men to have two wives at the same time.) The third register shows more of Maienhekau’s family members. His parents, Ryry (the mother) and Min (the father), are shown seated, while Maienhekau’s brother, a man by the name of Khaemwaset, pours a liquid offering for them. Behind him are two more seated family members. The lowest register shows a series of six seated people whose identities are not known.

Figure 27: A detail from the stela of Maienhekau showing the deceased and his wife seated on chairs. In front of them, a son makes an offering to the couple.

With all of these preparations in place—a mummified body protected in its coffin, tomb goods, offerings, and a funeral ceremony—the ancient Egyptians anticipated a successful passage into the afterlife. Scenes decorating tomb walls, and texts recorded on papyri, stelae, and other funerary monuments, give us a glimpse into how the Egyptians envisioned the afterlife. In many ways, the afterlife mirrored the world they inhabited during life. For example, tomb scenes depict individuals carrying out agricultural work in the afterlife, but there the fields always flourish and the harvest is always bountiful.

Figure 28: Painted facsimile of the decoration on the east wall of the tomb of Sennedjem. In this scene, Sennedjem and his wife carry out agricultural tasks in the afterlife. Sennedjem lived during Egypt’s 19th Dynasty (ca. 1295-1213 BCE). Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NYC. Painting by Charles K. Wilkinson, accession number 30.4.2.

Figure 29: In this scene from a diorama on exhibit in the Egyptian Gallery at Glencairn, the deceased, a woman named Isty, is shown being ushered in before Osiris after passing successfully into the afterlife. This diorama is based on a Book of the Dead funerary papyrus now in the collection of the Field Museum in Chicago.

While mundane tasks still existed after death, eternal life after death offered the promise of access to the divine in a way that was not possible on earth. After successfully entering the afterlife, the deceased could encounter Osiris, as well as other Egyptian deities. A good example of this can be seen in an inscription from the tomb of a man named Paheri:

“A beautiful funeral after a long life of excellent service. When old age is there and you arrive at your place in the sarcophagus and join the land in the necropolis of the west, become a living Ba. Oh may you be able to enjoy bread, water and breath. May you be able to transform into a heron, swallow, falcon, egret, according to your desire. May you cross (the Nile) in the barque without being driven back and having to sail with the current. May your life come back to you a second time …. May the doors of the horizon open up for you, and the bolts be untied for you. May you arrive in the hall of judgement and that the god who is in it greets you […] May you move according to your desire, may you leave every morning and return to your house every evening. May a lamp to be lit for you every night until the light (of the sun) illuminates your chest. May one say to you: ‘Come, come, into your house of the living!’ May you see Ra in the horizon of the sky and Amon at his rising. May your wakening be good every morning, destroying completely for you all demons. May you pass your eternity with a happy heart by the god's favor that is in you, your heart torture you not, and your food remain in its place.”

From this text we see that Paheri has lived a just life in accordance with the moral and ethical guidelines of his society. He has lived long and has planned well for his funeral and burial. As a result of these preparations, he is rewarded with eternity “with a happy heart.”

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Associate Curator, Egyptian Section

Penn Museum

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.