Glencairn Museum News | Number 6, 2022

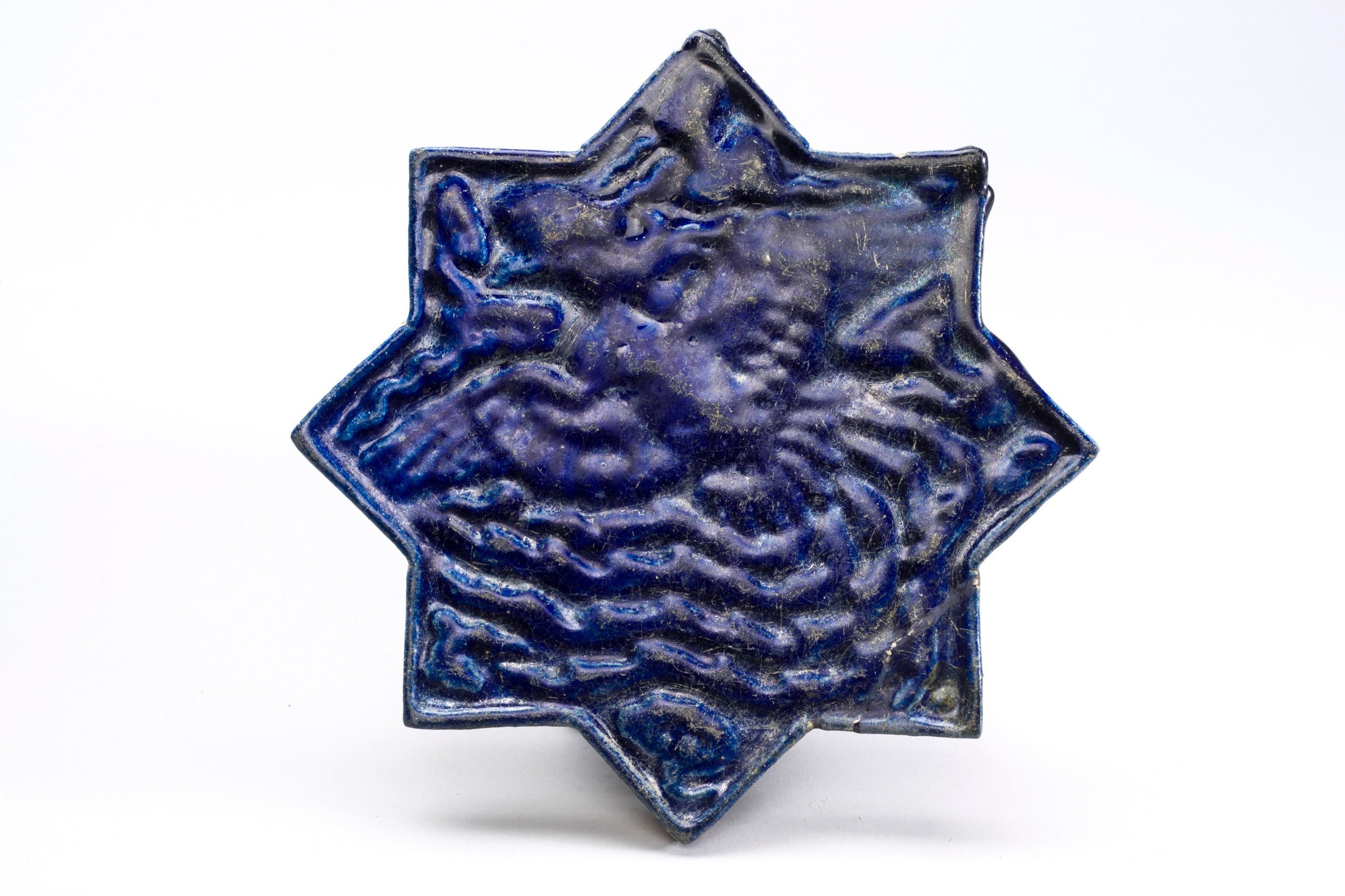

Left: Eight-pointed star tile in the Glencairn Museum collection with a representation of the Simurgh, a mythical bird, from the city of Kashan in 14th-century Iran. Right: A similar tile from 13th-century in the collection of the British Museum. Image courtesy of The Trustees of the British Museum, G.217.

The medieval ages, both in the East and the West, were complex times, much like ours. Despite a flourishing in the arts and sciences, fragmentation, competition over limited resources, and political strife were prevalent. And notwithstanding uncertainties and political turmoil, sometime during the 11th and the 14th centuries, as the Seljuk Empire was taking hold in a vast geographical area covering today’s Iran, Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, a rich visual repertoire was emerging in arts. In addition to calligraphy, geometric, and floral decorations, there was an appreciation of figural imagery which was visible not only on architectural decorations, but also on everyday portable objects made of paper, textile, glass, ceramics and metalwork. Figural imagery of the time included scenes from the royal court, entertainment with music and food, hunting, and polo playing; astrological symbols, scientific illustrations, stories from ancient legends, animals, as well as mythical creatures, such as the Simurgh.

Figure 1: Eight-pointed star tile in the Glencairn Museum collection with a representation of the Simurgh, a mythical bird from 14th-century Iran (ceramic glazed and luster-painted, 01.TL.304).

The origins and the methods of transfer of artistic imagery, as well as the context of their flourishing, have been the focus of numerous scholarly studies. What were the stories behind these figural images? Did they represent ancient mythologies, legends, and folklore transmitted through oral storytelling that are now lost? How did a visual language become so popular amongst people living within a vast geography with different cultural and ethnic backgrounds, and diverse belief systems and languages? And more importantly, how could a knowledge of this period be applicable to our lives today?

One of those objects from this period is now in the Glencairn Museum collection (Figure 1). With its mysterious depiction of a mythical creature, the Simurgh, it could provide an opportunity for us to exercise our empathy muscles in our understanding of the “other”—a skill we each need to develop to meet the complex challenges of our times such as fragmentation, inequities, and injustice. While we glimpse into this world of thriving creative imagination and take a closer look at the Simurgh tile through the lens of empathy, we can explore how an intentional approach to empathy-building might gradually enable us to learn something about ourselves: a recognition of the quality of expansiveness of the human heart to hold the “other” and the unfamiliar in a nonjudgmental field, which we may call: love.

The Glencairn Simurgh, a small, star-shaped tile with a central embossed depiction of the mythical bird, dates to 14th-century Iran, and currently adorns the wall near the entrance of the private family chapel on the fifth floor (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Islamic tiles embedded in the wall of Glencairn’s fifth-floor hallway, leading to the Chapel. The Simurgh tile is located on the right side of the right window bay.

This unassuming tile is accompanied by a few similar small pieces, most likely from the same provenance in 14th-century Iran (the city of Kashan), embedded into the wall of the hallway somewhat distant from each other. In their original use, these pieces would have been installed tightly like the pieces of a puzzle, along with hundreds like them, to cover a large wall, creating a sense of infinity through repetition of an ever-expanding geometric design, decorated with figures of animals, humans, flora, and mythical creatures (Figures 3–4). They were most likely mass-produced with molds and templates to meet popular demand for this type of imagery and decoration. The Glencairn Simurgh tile potentially adorned a building that once belonged to a wealthy ruler, or a government official, or perhaps a public space such as a school, a hospital, or a traveler’s lodge. Numerous examples of similar wall tiles can be found in museums around the world (Figures 5, 8–9).

Figure 3: A 13th-century Iranian tile panel in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 91.1.106.

Figure 4: A 13th-century Iranian tile panel in the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin. Image courtesy of the National Museums of Berlin, Museum of Islamic Art / Johannes Kramer CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, I.3865.

The Simurgh is a mythical creature and an ancient symbol that appears across time and cultures and in different legends, often with varying roles, qualities, and names, such as Phoenix, or Zumrud-u Anka. It is likely that the depictions of this mythical creature were assigned multiple meanings by those who viewed it over time, even during the times and places where it was first created and used. In this exploration we will attempt to understand the Simurgh tile through the contemporaneous worldview of Sufism, which was prevalent at the time and across the geographies where a tile like the one in Glencairn might have been produced and used.

The Simurgh and the Philosophy of the Oneness of Being

The flourishing of the arts during this period corresponds with the travels of wise men and scholars of Islam, who contributed to the development of spiritual lives and the creative imagination of the ruling elites, the artists, as well as ordinary people. Their teachings planted the seeds of Islamic mysticism, or Sufism, where one of the recurring messages was an understanding of the “Oneness of Being” (Wahdat al Wujud)—a recognition of Unity within Diversity, and Love as the origin, as well as the destination, of all things in existence. This worldview has been reflected as a central theme in all forms of Islamic art and continues to guide many Muslims’ understanding of the self, identity, ethics, values, and behaviors, informing their engagement with the “other,” including all living beings and the environment. Kabir Helminski, a modern Sufi teacher and author, explains the foundational tenet of the Oneness of Being in Islamic thought:

“Traditional wisdom conceives of the Whole in terms of a single Creative Power acting on different levels through different means, or reflectors, to produce an infinite variety of creative results. In other words, everything that exists is the manifestation of a single Source of Life and Being. (1)

Figure 5: A 13th-century Iranian tile with the Simurgh from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 12.49.4.

In Persian literature of the 12th century, the Simurgh takes center stage in Farid Ud-Din Attar’s epic poem, The Conference of the Birds (Mantiq at-Tayr). This book (Figures 6–7) was written in the territory of present-day Iran, not too far from major ceramic producing centers of the time, where a variety of ceramics and tiles similar to the Simurgh tile at Glencairn would have been crafted. Attar’s work is considered as one of the reference books when it comes to understanding medieval Islam and the Sufi thought that prevailed at the time. Other Sufi teachers before and after Attar often used similar metaphors, stories, and imagery to impart ancient wisdom. Although we do not have direct evidence of a specific text dictating the design of a specific artwork from this period, it is quite possible that this wealth of imagery was shared widely through oral storytelling traditions, and would have inspired the imaginations of artists, elites, and ordinary people alike, contributing to the development of a shared culture and a shared visual language.

Figure 6: Cover of "The Concourse of the Birds," Folio 11r, c. 1600 CE. Painting by Habiballah of Sava (Iranian, active c. 1590–1610). Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 63.210.11.

Figure 7: Detail of the cover of "The Concourse of the Birds," Folio 11r, c. 1600 CE. Painting by Habiballah of Sava (Iranian, active c. 1590–1610). Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 63.210.11.

Figure 8: A 13th-century Iranian tile in the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin. Image courtesy of the National Museums of Berlin, Museum of Islamic Art / Christian Krug CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, I.1988.10.

The Conference of the Birds describes the arduous journey of the world’s bird-folk to find the Simurgh, their One True King. Many birds take part in this journey, but as they go through dangerous valleys and mountains, only thirty of them remain to arrive at their destination on top of the Mountain of Qaf, where the Simurgh is said to reside. Their first gaze on the Simurgh makes them realize that they themselves were the Simurgh, the One, they were looking for all along:

“Their life came from that close, insistent sun

And in its vivid rays they shone as one.

There in the Simurgh’s radiant face they saw

Themselves, the Simurgh of the world—with awe

They gazed, and dared at last to comprehend

They were the Simurgh and the journey’s end.”

—Farid Ud-Din Attar, The Conference of the Birds

Translators of Attar’s The Conference of the Birds drop a note at this crucial moment in the book that it is important here to understand a linguistic pun that would be easily understood by Persian-speaking people, but could leave others oblivious: si means “thirty,” and morgh means “bird(s)”; the “si morgh” see the “Simurgh.” (2) The journey of the thirty birds through valleys, mountains, and deserts, symbolizes the stages of the self towards becoming a “complete human being” on the Sufi path—Self-knowledge, Self-control, Objective Knowledge, Inner Wisdom, Being, Selfless Love, and Sustaining the Divine Perspective—the ability to always see events and people from the highest perspective of Love and Unity and not to slip into egoistic judgment and opinion, where at the final stage of Divine Intimacy awareness of one’s connection to the Divine Source, the self, and all perceived multiplicity, dissolve into nothingness through a deep recognition of the essential “Oneness of Being.” (3)

Figure 9: A 14th-century Iranian tile in the Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin. Image courtesy of the National Museums of Berlin, Museum of Islamic Art / Johannes Kramer CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, I.1618.

The Simurgh continues to explain this mystery:

“I am a mirror before your eyes,

And all who come before my splendor see

Themselves, their own unique reality;

You came as thirty birds and therefore saw

These selfsame thirty birds, not less nor more;

If you had come as forty, fifty, would appear;

Though you have struggled, wandered, travelled far,

It is yourselves you see and what you are.”

—Farid Ud-Din Attar, The Conference of the Birds

We may never find out whether Raymond Pitcairn, who purchased the Simurgh tile centuries later and asked that it be placed on a particular wall right next to the entrance of his family’s private chapel, knew that the symbolism of the Simurgh was so closely related to the philosophy of oneness he was exploring, as his exquisitely decorated sanctuary reflects throughout. Here on the fifth floor, after one looks at the Simurgh tile, one can go into the chapel and see the two Greek letters, alpha and omega, which appear side-by-side in the mosaic on the chapel ceiling (Figures 10–11). Taken together, they clearly refer to a passage from the New Testament’s Book of Revelation (22:13): “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End, the First and the Last.” Pitcairn understood the meaning of these letters and would have accepted the Swedenborgian interpretation of the passage. According to the theological works of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772), “God is called the Alpha and the Omega, the Beginning and the End, because alpha is the first letter in the Greek alphabet and omega is the last; so together they mean all things as a whole.” In other words, “on every level of existence” God is “the one and only entity, the source of all things” (True Christianity ¶19).

Figure 10: Alpha and omega, respectively the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, are written in mosaic in the ceiling of Glencairn’s Chapel.

Figure 11: The mosaic ceiling of Glencairn’s Chapel.

Empathy as a Portal to Love

“Out beyond ideas of wrongdoing and rightdoing,

There is a field.

I will meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass, the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, languages, even the phrase each other doesn’t make any sense.”

—Rumi (4)

During a recent Designing for Empathy Workshop at Glencairn Museum (Figure 12), the Simurgh tile was the focus of the last empathy-building experience of the day. It would be useful here to provide a quick overview of the Designing for Empathy framework.

Figure 12: The Designing for Empathy Workshop at Glencairn Museum (March 5, 2022).

The Designing for Empathy framework finds its inspiration in the ancient wisdom of the “Oneness of Being” (Wahdat al Wujud), and the fact that a belief in the oneness of all things has been explored in many languages, cultures, and traditions of wisdom for thousands of years. Other examples include Advaita, Ubuntu, Hishuk Ish Tsawalk, Tikkun olam, Yin and Yang, Unity, Interconnectedness, Nonduality, and Interbeing—each offering a nuanced articulation of a central belief in oneness, worthy of deeper exploration.

As the Designing for Empathy framework taps into humanity's collective ancient wisdom, it explores “oneness” as a “mindset”—a master perspective, inspiring how we see our world and our place in it, and informing how we might design our tools, utilize our knowledge, technologies, and systems towards harmonious engagements with the “other” and the whole, of which we are all a part. Developing a Oneness Mindset, regardless of our cultural and religious belief or non-belief, might remind us to meaningfully engage with the whole and each of its unique and diverse elements, through acts of compassion, altruism, and love.

Within this context, empathy can be described as a form of perception that enables us to connect with ourselves and with others while awakening us into our oneness. Empathy does not mean the ability to completely understand or feel another’s experience, perspective, or emotions, which is physiologically not possible. Instead, through a recognition of the value of each unique element that makes up the whole, empathy can simply be an act of the generosity of the heart that is expansive, and can momentarily place the ego aside, to offer a non-judgmental “heart-space” for the “other” to just “be.” We may call this capacity of the heart to fully acknowledge the “other”: love.

Kabir Helminski describes the Sufi perspective on love as, “Love unites us with everything and allows us to know that we ‘are’ everything.” He continues to explain:

“Love is the tamer of ego. This is because it makes it possible for us to acknowledge for another the same significance and importance that we first attributed only to ourselves. The egoism that initially shaped our whole lives encounters in love a living power that rescues it from its isolation and restores it to contact with something greater than itself. . . . Holistic and unconditional love, agape, is the unity in which duality disappears. It is as if a certain internal boundary has vanished. With agape, what we love is ourselves, the way a mother loves her child as herself. This is the meaning of loving another as yourself—transcending our phenomenal borders and experiencing ourselves in another and the other in, not apart from, us.” (5)

Within the Designing for Empathy framework, empathy-building is an intentionally designed, transformative, perspective-shifting and perception-expanding lived experience, which utilizes the ingredients of the “Alchemy of Empathy” (such as proximity, vulnerability, storytelling, awe and wonder, and play), enabling us to observe, notice, and articulate the filters and biases that affect our perception. Self-knowledge through empathy-building empowers us with the ability to develop a capacity for articulation, accountability, and self-correction.

An intentional expansion of our perception through empathy-building might lead us to perceive the qualities of love within and around us, and through love, active service towards the preservation of our biological and cultural diversity in our oneness.

We are Fragments Ourselves, Yearning to Become Whole

“You are not just a drop, you are the entire Ocean within a drop.”

—Rumi

“The drop that truly knows itself is aware of the Ocean.”

—Kabir Helminski

The Glencairn Simurgh tile stands as an enduring metaphor for fragmentation, othering, belonging, and becoming one. Originally designed as an integral part to something much greater than itself, this tile was separated from the whole at some point in time and found itself in an entirely foreign context—somewhat alienated, lonely, and fragmented like many of its contemporaries that are now scattered in museums and private collections around the world. The only chance the Simurgh tile has of becoming alive again is in others’ imaginations, when its viewers recognize its true essence and acknowledge it, giving it a meaning by placing it in a greater context.

Intentional empathy-building enables us to recognize our capacity and limitations in our understanding of the “other.” We experience the many filters through which we perceive the “other,” such as our sociocultural background, belief systems, and our worldview. Developing a knowledge of the self within the context of the Oneness Mindset can inspire us to develop attitudes, behaviors, and healing solutions that are harmonious with All. Recognizing our inherent biases, worldview, and sociocultural background that affect our perception of the “other” is essential for us to be able to acknowledge and control them towards self-correction, and accountability.

A lived experience of intentional empathy-building allows us to notice that at any given moment, there is a variety of thinking, perception, and meaning-making simultaneously occurring within, and around us. We notice that we may have similar thoughts with others, but for different reasons. We experience having very different thoughts from the others while sharing the same space. We discover the multitudes of ways of perception, and that others’ ideas and perceptions can expand our own to help us create new perspectives and new narratives. We experience that the ideas that we thought were opposites are more fluid than we expected them to be when they are shared in a non-judgmental space, and are held with sincerity, trust, and love in a community.

At this very moment, we are facing a choice between self-destruction and a much-needed awareness of the oneness of our existence, that we each are integral to a whole—all of humanity, our world, and the universe as we know it. As we utilize an unassuming object such as the Simurgh tile, to explore different perspectives and different ways of perception through empathy-building, we experience patience, vulnerability, humility, courage, acceptance, and trust. We recognize through a real-life shared experience that we each carry an expansive quality in our hearts that can hold all, even the opposites, in the same space, which we may call: love. And, when we experience love, we find our true meaning and purpose, as we are empowered with the self-knowledge of being integral to something much greater than ourselves, and of our unique and shared capacity for healing the whole through acts of compassion, altruism, and—love.

Elif M. Gokcigdem, PhD

Elif Gokcigdem received her BA in Art History from Mimar Sinan University, and her MA and PhD in Art History from the Istanbul Technical University with a specialization on medieval Islamic arts. She completed her Museum Studies graduate certification program at The George Washington University.

Endnotes

1. Kabir Helminski, Living Presence: The Sufi Path to Mindfulness and the Essential Self. TarcherPerigee, 2017, p. 23.

2. Farid Ud-Din Attar, The Conference of the Birds. Translated by Afkham Darbandi and Dick Davis. (Penguin Classics, 1984): 219.

3. Kabir Helminski, The Knowing Heart: A Sufi Path of Transformation. (Shambhala Publications, 1999): 28–29.

4. Coleman Barks, Open Secret (Putney, VT: Threshold Books, 1982).

5. Kabir Helminski, Living Presence, p. 190–91.

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox (12 times per year)? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.