Glencairn Museum News | Number 1, 2023

Raymond Pitcairn shows a scale model of Glencairn to two of his grandsons in Glencairn’s Great Hall (c. 1955).

“One of the most striking differences between art of the past and that of today is the fact that the ancient art objects were not isolated things which were more or less forced into their surroundings, they were part and parcel of the temple, the acropolis, the house or tomb for which they were made. Our private collections as well as our museums are full of things which do not really fit their surroundings [. . .].”1

With these words, which Raymond Pitcairn (1885–1966, Figure 1) wrote to his brother Theodore in January 1922, the Philadelphia-born businessman summarized one of the central difficulties that arises when displaying medieval art in a museum: the fact that artifacts from the Middle Ages were created as functional objects, oftentimes integrated into a larger architectural setting. In that same letter, Pitcairn took a stand on how to surmount this issue: he expressed the wish to create a studio “which would be a Romanesque or early Gothic room or small building” to house his collection of medieval sculpture and stained glass.2 This wish eventually led to the creation of Glencairn, an impressive Neo-Romanesque fortress in Bryn Athyn that served as the Pitcairns’ private residence from 1939 on. Throughout this castle-like building, the collection amassed by Pitcairn was displayed in a setting that followed his longing for an architectural framing of these artifacts.

Figure 1: Carving intended for installation above the Glencairn front door, no date (1930s). Gabriele Pitcairn Pendleton and Raymond Pitcairn appear in the photo. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers, Series V: Private Life.

The creation of a medieval context to display objects from the Middle Ages was far from being Pitcairn’s invention: the quest for ambiance and an appropriate setting is indeed one of the main questions that have shaped the history of museums of medieval art since the early nineteenth century.3 This article aims to place Glencairn in the larger picture of major museums of medieval art in the decade of its creation, the 1930s. As stated by Jennifer Borland, “At Glencairn, past and present collide in the juxtaposition of imaginative medievalist style and ‘authentic’ medieval things.” (See Jennifer Borland, “A Medievalist in the Archives: Exploring Twentieth-Century Medievalism at Glencairn,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 1, 2019.) Despite its character as a private residence, Raymond Pitcairn’s architectural creation chiefly exemplifies the main questions that were discussed by contemporary curators of medieval art in charge of public collections: the role that architecture and context should play in the display of an object, as well as the different layers of authenticity and fiction that unfold in this process.

The construction of Glencairn, though envisioned since the mid-1920s, did not truly begin until the early 1930s, once the adjacent Bryn Athyn Cathedral had been completed and the initial shock of the 1929 Wall Street crash was surmounted.4 (See “Why Did Raymond Pitcairn Build Glencairn? From Cloister Studio to Castle,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 1, 2022.) Dedicated in December 1938, this Neo-Romanesque castle (Figure 2) would act both as a private home and as a receptacle for Pitcairn‘s collection of medieval art. The so-called Great Hall (Figure 3) serves still to this day as a central display setting, in which the complexity and richness of this medievalist reverie of the 1930s can be best described and dissected.

Figure 3: The Great Hall of Glencairn, Bryn Athyn, 1990. The three windows are replicas of Chartres Cathedral windows (see Figure 5, windows 2 and 4).

First, this vast space contains original medieval sculptures that were collected by Pitcairn to serve as inspiration for the craftsmen in charge of building the adjacent Bryn Athyn Cathedral.5 A well-known example is the so-called Slim Princess (Figure 4), a mid-twelfth-century sculpture column of a haloed queen that Pitcairn purchased from the dealer Georges Demotte in 1923.6 (See Julia Perratore, “Glencairn’s Slim Princess: A Twelfth Century Beauty Queen,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 6, 2015.)

The original medieval sculptures of the Pitcairn collection do not stand isolated in the Great Hall: these objects were arranged together to build an integrated display concept that did not reproduce their original setting in Europe. Instead, these compositions brought artworks from diverse geographical origins together, fabricating a fictitious new context for the objects involved. In the case of the Slim Princess, it was framed by a 12th-century stone portal, as well as by two Romanesque capitals. Assemblies such as this one were in turn enclosed by modern architectural materials, such as the brick stone wall that surrounds the Slim Princess.

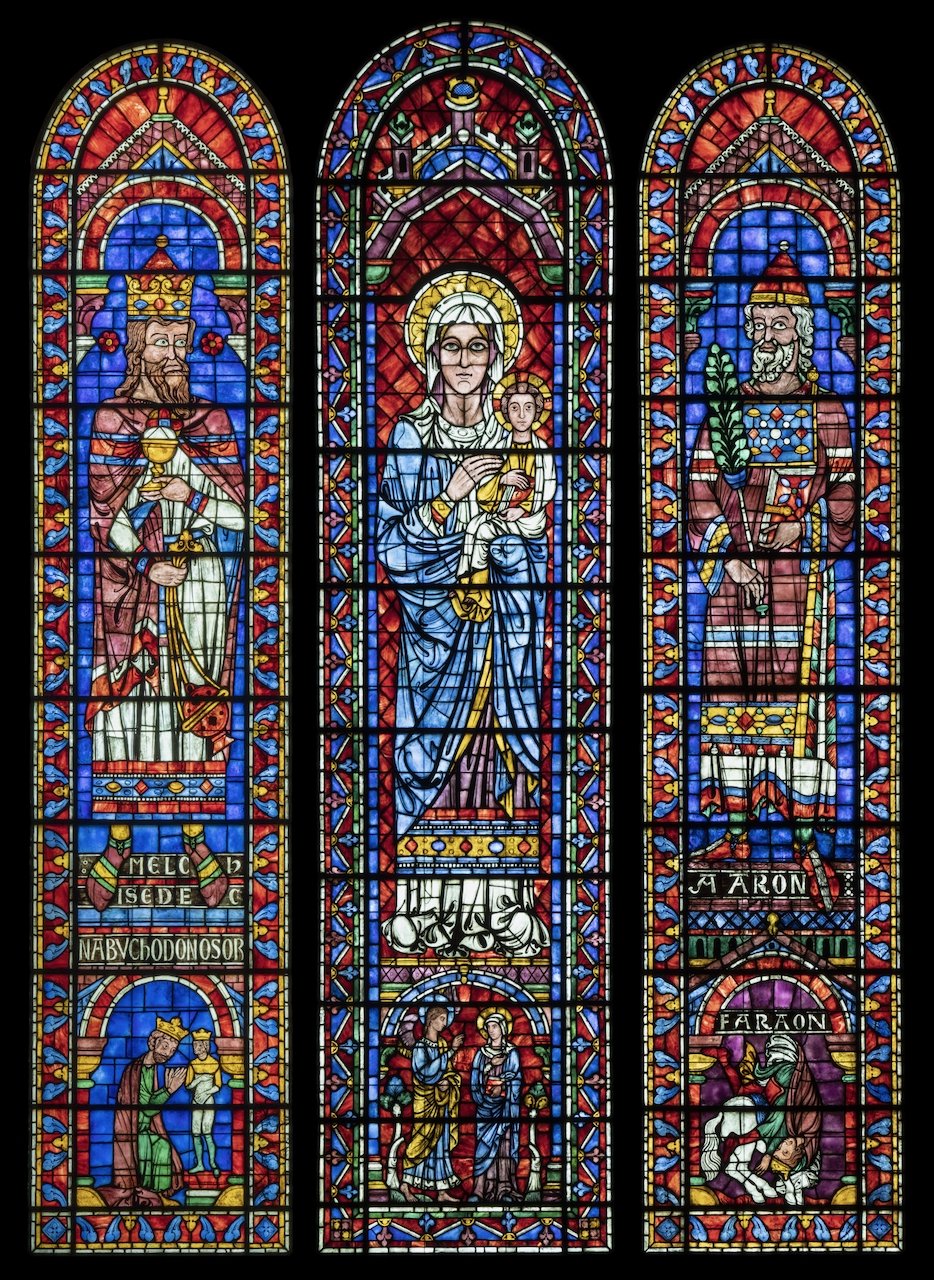

The panels of stained glass that decorate the windows of the Great Hall (Figure 3) are another example of this mixture of medieval and modern architectural elements. The east wall windows are covered with original medieval glass from the Pitcairn collection. In contrast, the six windows on the west and north walls are full-scale replicas of stained-glass panels in Chartres Cathedral (Figure 5), located around sixty miles southwest of Paris. (See “A Heavenly Light: The Bryn Athyn Stained Glass Factory and Studio,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 10, 2015.)

Figure 5: Stained-glass windows under the north rose window at Chartres Cathedral, Chartres, 8 October 2019. Photograph: Rolf Kranz. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

In 1925, Pitcairn purchased five full-size drawings of the Chartres windows. Together with a sixth rubbing that was made at his request in 1932, these reproductions were used to replicate the original Chartres stained-glass windows in the Great Hall (Figures 6–8).7

Figure 6: The Great Hall under construction, Bryn Athyn, no date (1930s). The Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers, Series II: Glencairn.

Figure 7: The Great Hall under construction, Bryn Athyn, no date (1930s). The Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers, Series II: Glencairn.

Figure 8: The Great Hall of Glencairn, Bryn Athyn, 2022. The three windows are replicas of Chartres Cathedral windows (see Figure 5, windows 1, 3 and 5).

The Great Hall’s Slim Princess and stained-glass windows from Chartres represent two instances where the concepts of authenticity and fiction intertwine at Glencairn, ranging from actual medieval objects and replicas of original artworks to a Neo-Romanesque setting where they were brought together. These three elements (original objects, replicas, and an architectural frame) were all present in museums of medieval art at the time of Glencairn’s dedication in December of 1938.

Housing a collection of artifacts from the Middle Ages in a medieval architectural setting had been most prominently done at the Cluny Museum in Paris. Very much like Glencairn Museum, the origins of the Cluny Museum can also be traced to a private individual and their collecting activity. Alexandre Du Sommerard (1779–1842) was an eminent collector of medieval art in early nineteenth-century France who played a central role in buying and protecting artifacts disseminated in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Du Sommerard displayed his collection at the Hôtel de Cluny, the former Parisian residence of the Abbots of Cluny, a fifteenth-century building (Figure 9) situated in the Parisian neighborhood known as the “Latin Quarter.” The French State purchased Du Sommerard’s collection in 1843, establishing it as a national museum dedicated to the medieval and early Renaissance periods.8

The Cluny Museum is considered to have been a key prototype for many European museums of sculpture and decorative arts.9 At the time of Glencairn’s creation, it still retained its nineteenth-century layout, which would be completely refurbished in the aftermath of the Second World War. The medieval interiors of the Hôtel de Cluny, such as the Chapel (Figure 10), served as a scenic display environment for objects from the Middle Ages, providing an architectural context such as the one that Pitcairn desired for his collection in Bryn Athyn in his 1922 letter.

In the 1930s, most other rooms at the Cluny Museum lacked the medieval ambiance of the Chapel (Figure 10) and instead had a certain material or technique as their central theme.10 The Enamel Room (Figure 11) offers an interesting comparison point to Glencairn’s Great Hall: in both spaces, objects created at different stages of the Middle Ages, and coming from diverse places, were brought together. The Enamel Room housed a wide range of tapestries, including the famous Lady and the Unicorn series, as well as many examples of Gothic sculpture and stained glass. These artifacts surrounded several display cases that showcased the museum’s rich collection of vitreous enamels. Despite its medieval architectural entourage, the assembly of objects at the Cluny Museum’s Enamel Room was in a way just as fictional as the Slim Princess’s display at Glencairn’s Great Hall, where the haloed queen is framed by sculptural elements coming from other churches and buildings. Though original architectural elements from the Middle Ages were used whenever possible, the Cluny Museum’s aim was not to accurately reconstruct the churches, palaces, and castles where the collection’s objects were found. Instead, it provided an eclectic display frame for its broad collection, a display that was shaped by the vision and taste of the curators in charge.

The Enamel Room’s windows provide another interesting parallel to the 1930s Pitcairn residence in Bryn Athyn: original stained-glass fragments from a handful of sacral spaces, including the spectacular Parisian Sainte Chapelle, were integrated into the window’s glass frame (Figure 11). This arrangement kept the functional character of these stained-glass pieces alive, no longer in a liturgical, but in a museum setting.11 The inclusion of multiple fragments in a single window surrounded by transparent glass, as an array of canvases on a wall, differs from the implementation of stained glass at Glencairn’s Great Hall. At the Cluny Museum, original artworks such as the mentioned Sainte Chapelle pieces were at the heart of the institution’s display concept. In Bryn Athyn, the described Chartres replicas were seamlessly integrated into the Great Hall’s structure, thus hindering the layman’s ability to distinguish medieval and modern. Despite this different way of dealing with original artworks and replicas, the Cluny Museum shows how authenticity and fiction coexisted in the second half of the late nineteenth century in a museum that essentially focused on displaying medieval pieces.

However, replicas and casts were important (and oftentimes contested) elements of European museums in the 1930s, and Pitcairn was able to witness this during his multiple trips to the Old Continent. In 1922, Pitcairn traveled to Paris in the context of his collecting activities.12 During his time in the French capital, he visited the Musée de Sculpture comparée (Museum of Compared Sculpture), located at the Trocadéro Palace, in front of the Eiffel Tower.13 This institution assembled an impressive collection of cast sculptures that showcased the evolution of French medieval art, allowing visitors and experts to compare church portals and monumental sculptures scattered across the country.14

Figure 12: Postcard depicting the Avallon Portal and the Corbeil Sculpture Columns, Ernest Le Deley, 1900, image no. 18.

A postcard dating to the early twentieth century (Figure 12) shows an interesting display arrangement at the Trocadéro Museum: a replica of the church portal at Avallon, Burgundy, framing two casts representing sculpture columns from a church in Corbeil, near Paris.15 Thanks to this composition, the visitor could contrast an example of High Romanesque sculpture represented by the Avallon portal with two sculptures representing an early example of Gothic style. This assembly made it possible to surmount the geographical distance between the original pieces to enable their juxtaposition. This combination of portal and sculpture columns pursued, in contrast to Glencairn’s Slim Princess and her framing, the portrayal of an art historical evolution.

Replicas and sculpture casts were not foreign to museums that collected and displayed original artworks. Their utility to fill gaps in the collection and provide a retrospective view of art historical masterpieces scattered across the continent turned them into an important part of museum collections in the nineteenth century.16

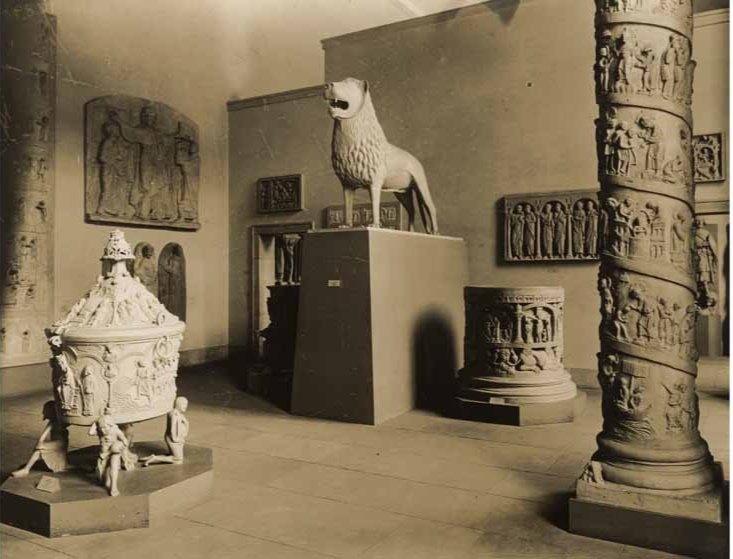

At the time of Glencairn’s creation, the Berlin State Museums’ collection of medieval sculpture was placed in a new museum: the Deutsches Museum (German Museum), which no longer exists, at the time located next to the Pergamon Museum in Germany’s capital. This institution’s display esthetic (Figure 13) reflected the 1930s taste for neutral walls and a spacious placement of objects, in contrast to the cramped nineteenth-century arrangements that still subsisted in other museums (Figure 11). Since the curator’s goal was to illustrate the development of German art over the centuries, several rooms were dedicated to showcasing, besides original artworks, replicas of masterpieces located outside of Berlin. The Room of the Tomb of St. Sebaldus (Figure 13) featured key pieces located in church treasuries and museums in Nuremberg, Hildesheim, and Braunschweig, among others. This arrangement drew upon the Berlin State Museum’s extensive cast collection, which was a central focus of acquisitions in the second half of the nineteenth century.17 In the late 1920s, during the final stages of the Deutsches Museum’s creation, its director faced critics for focusing on the display of original artworks, and not having the cast collection be at the heart of the new institution, unleashing a heated debate in the press.18 In the end, replicas only played a supplementary role in the museum’s display when the Deutsches Museum was inaugurated in 1930. The polemic around the usage of casts to grant art historical context to the sculpture collections of the Berlin State Museums proves to what extent the concepts of authenticity and fiction, original and copy, were not inherently “good” and “bad” at the time of Glencairn’s creation.

Figure 13: Room of the Tomb of St Sebaldus, Deutsches Museum, Berlin, 1930–1934. Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Zentralarchiv, ZA 2.3./05271. Hildesheim Baptismal Font, the Braunschweig Lion, and the Bernward Column. Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 4.0.

These European examples give a limited overview of how “old” and “new” museums of medieval art dealt with original artworks in the 1930s, providing art historical context and ambiance through architectural elements and replicas. While reflecting on the difficulties that the display of medieval art entailed in 1922, Pitcairn specifically mentioned an existing location that he considered to be exemplary: “Of course beautiful things can be done where an artist understands what he is about. Barnard’s cloister stands head and shoulders above the private and museum collections because his objects were made part of the building which he built them into.”19

Sculptor George Grey Barnard’s (1863–1938) Cloisters in New York, opened to the public in 1914 and acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1925, make a crucial twist in the discussed dichotomy of authenticity and fiction in museums of medieval art. By reconstructing several French cloisters in Washington Heights, New York, as a display setting for objects from the Middle Ages, Barnard took to another level the efforts to provide context for medieval artworks. Many scholars have drawn links between the Cluny Museum and the Barnard Cloisters, seeing the French example as a possible inspiration for the arrangement undertaken in this first Cloisters museum.20 In the absence of actual Romanesque or Gothic buildings in the United States that could be repurposed to house a museum, Barnard’s assembly in Upper Manhattan constituted a groundbreaking effort to create an atmospheric experience for the display of medieval artifacts.21

The current site of The Met Cloisters in Fort Tryon Park was inaugurated in May 1938, only half a year before the dedication of Glencairn. Based on a thorough study of European medieval architecture, The Cloisters’ outer structure, in the form of a Romanesque monastery, is similar in spirit to Glencairn’s majestic appearance towering over Bryn Athyn. The Cloister’s interior lacked the crowded distribution of the Cluny Museum but stood in stark contrast to the neutral arrangement present in state-of-the-art institutions such as the Berlin State Museums.22 As stated by James J. Rorimer, one of the steering forces behind the project, “The building [. . .] is not copied from any mediaeval building, nor is it a composite of various buildings. [. . .] It was our purpose to provide an appropriate, unified ensemble for the diverse architectural elements.”23 This consolidated character sets apart The Cloisters from the previous French and German examples, where the lines between medieval and modern were more visible. This seamless integration of medieval and modern elements in a unified ensemble also characterized Glencairn’s Great Hall, which in contrast drew upon replicas to enhance its medieval holdings. The Cloisters and Glencairn can both be considered highlights of late 1930s American medievalist architecture: the former was conceived as a public museum, the latter as a private home. (See Julia Perratore, “The Cloisters Connection,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 3, 2015.)

Despite its standalone function as a private residence in the context of 1930s museums of medieval art, Glencairn shared many of the challenges that public museums on both sides of the Atlantic faced when thinking about how to best display their collections of art of the Middle Ages. Raymond Pitcairn steered away from the encyclopedic and art historical goals of the described European museums while engaging in many solutions employed in Paris, Berlin, and New York to contextualize medieval objects in a museum setting. Since 1982, Glencairn has been open to the public as a museum, offering visitors a privileged glimpse into a spectacular achievement of 1930s American medievalism at the crossroads of authenticity and fiction.

Iñigo Salto Santamaría

Technical University of Berlin

Endnotes

1. Raymond Pitcairn to Theodore Pitcairn, 12 January 1922. Cited after: “Why Did Raymond Pitcairn Build Glencairn? From Cloister Studio to Castle,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 1, 2022: https://www.glencairnmuseum.org/newsletter/2022/2/22/why-did-raymond-pitcairn-build-glencairn-from-cloister-studio-to-castle. See also: E. Bruce Glenn, Glencairn: The Story of a Home. Bryn Athyn: Academy of the New Church, 1990, p. 162f.

2. Ibid.

3. For a comprehensive overview of the history of museums of medieval art, see: Wolfgang Brückle, Pierre Alain Mariaux and Daniela Mondini (eds.), Musealisierung mittelalterlicher Kunst. Anlässe, Ansätze, Ansprüche. Berlin/Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2015. See also: Wolfgang Brückle, “Aux racines de la mise en scène historiciste: Observations sur les premières décennies de l’art médiéval dans un contexte muséal,” in: Geneviève Bresc-Bautier and Béatrice de Chancel-Bardelot (eds.), Un musée révolutionnaire: Le Musée des Monuments français d'Alexandre Lenoir. Paris: Musée du Louvre, 2016, p. 271–281.

4. Glencairn: The Story of a Home…, p. 18.

5. Ibid, p. 13f.

6. Jane Hayward and Walter Cahn, Radiance and Reflection: Medieval Art from the Raymond Pitcairn Collection. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982, p. 98–99. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/radiance_and_reflection_medieval_art_from_the_raymond_pitcairn_collection

7. Glencairn: The Story of a Home…, p. 134.

8. Pierre-Yves Le Pogam, “Il Medioevo al museo. Dal «Musée des Monuments français» ai «Cloisters»,” in: Enrico Castelnuovo and Giuseppe Sergi (eds.), Il Medioevo al passato e al presente, Arti e storia nel Medioevo 4. Turin: Einaudi, 2004, 759–784, at 765–767.

9. Kathleen Curran, The Invention of the American Museum, From Craft to Kulturgeschichte, 1870-1930. Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2016, p. 16.

10. Edmont Haraucourt, L'Histoire de la France expliquée au musée de Cluny. Guide annoté par salles et par séries, par Edmond Haraucourt, directeur du musée de Cluny, membre de la Commission des monuments historiques. Paris: Librairie Larousse, 1922, p. 8–10: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6524796h/f16.double.

11. Ibid…, p. 130–132: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k6524796h/f150.double.

12. Radiance and Reflection…, p. 34f.

13. Ibid.

14. On the Musée de Sculpture comparée, see: Dominique Jarrassé and Emmanuelle Polack, “Le musée de Sculpture comparée au prisme de la collection de cartes postales éditées par les frères Neurdein (1904–1915),” Les Cahiers de l’École du Louvre 4 (2014): http://journals.openedition.org/cel/476.

15. For more information on these casts, see: https://www.citedelarchitecture.fr/fr/oeuvre/portail-cycle-des-rois-mages-resurrection-et-descente-aux-limbes, https://www.citedelarchitecture.fr/fr/oeuvre/statue-colonne-une-reine-la-reine-de-saba and https://www.citedelarchitecture.fr/fr/oeuvre/statue-colonne-un-roi-salomon.

16. The Cast Courts at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, inaugurated in 1872, constitute a prominent example of this phenomenon. On the history of the V&A Cast Courts, see: History of the Cast Courts (Produced as part of Designing the V&A), Victoria and Albert Museum: https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/history-of-the-cast-courts.

17. Thomas W. Gaehtgens, Die Berliner Museumsinsel im Deutschen Kaiserreich: Zur Kulturpolitik der Museen in der wilhelminischen Epoche. Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 1992, p. 14.

18. For a detailed overview on the 1927 polemic between Theodor Demmler (director of the Berlin State Museums Sculpture Collection) and Oscar Wulff (Professor at the University of Berlin), see: Frank Matthias Kammel, “‘Neuorganisation unserer Museen’ oder vom Prüfstein, an dem sich die Geister scheiden. Eine museumspolitische Debatte aus dem Jahre 1927,” Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 34 (1992), p. 121–136: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4125896.

19. Raymond Pitcairn to Theodore Pitcairn, 12 January 1922. Cited after: “Why Did Raymond Pitcairn Build Glencairn? From Cloister Studio to Castle,” Glencairn Museum News, no. 1, 2022: https://www.glencairnmuseum.org/newsletter/2022/2/22/why-did-raymond-pitcairn-build-glencairn-from-cloister-studio-to-castle.

20. William D, “Traditions et innovations au musée des Cloîtres,” in Jean-René Gaborit, Sculptures hors contexte, Paris: Musée du Louvre, 1996, p. 93–119, at p. 95.

21. On the creation of The Cloisters, see: Timothy B. Husband, Creating the Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, v. 70, no. 4 (Spring 2013): https://www.metmuseum.org/art/metpublications/Creating_the_Cloisters.

22. See Julien Chapuis, “Bode und Amerika, Eine komplexe Beziehung,” Jahrbuch Preussischer Kulturbesitz 43 (2006), p. 145–176, at p. 164.

23. James J. Rorimer,Medieval Monuments at the Cloisters, as They Were and as They Are, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1941, p. 6: https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll10/id/125774/rec/1.