Glencairn Museum News | Number 10, 2023

Limestone canopic jar with the head of the jackal god Duamutef from the New Kingdom site of Dra Abu el-Naga. Canopic jars served as protective vessels for the vital organs of the deceased. The jar featuring Duamutef safeguarded the stomach. This object will be on loan to Glencairn Museum from the Penn Museum beginning in 2024. (Penn Museum 29-87-516A&B, image courtesy of the Penn Museum)

Figure 1: Drawing of a bowl in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow (I.1.a 4777). This bowl dates to the Naqada I period (3900–3650 BCE).

An earlier Glencairn Museum News article, “Cats, Lions and the Fabulous Felines of Ancient Egypt,” examined the significant role of the cat in ancient Egypt. Naturally, one might wonder, did “man’s best friend”—the dog—have a similarly exalted position in ancient Egypt? For modern Americans, this may be a reasonable question to ask. Recent estimates report that 25% of American households have at least one cat as a pet, while around 38% of us have a dog at home, meaning that there are almost sixty million cats and just over seventy-six million dogs that hold a special place as “companion animals” in our homes.

Archaeological evidence and ancient textual sources provide substantial indications of human and canine interaction in ancient Egypt. Early depictions of domesticated dogs indicate that they served as hunting aides. One example from which we can infer this collaboration is the decoration on a painted bowl now housed in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow, which depicts a man holding a bow and arrows while grasping the leashes of four dogs (Figure 1). Subsequent portrayals of hunting scenes in tombs from the Old Kingdom (2625–2130 BCE) and Middle Kingdom (1980–1630 BCE) (Figure 2), as well as on materials originating from the New Kingdom (1539–1075 BCE), show that dogs continued to accompany both royal and non-royal Egyptians on hunting expeditions (Figure 3). In addition to functioning as hunting partners, dogs may have aided shepherds, served as watchdogs, or provided companionship.

Figure 2: On the left is a scene from the Sixth Dynasty tomb of Mereruka at Saqqara showing hunting dogs attacking desert game, photo courtesy of https://www.flickr.com/people/manna4u/. The relief on the right is a fragment from the Eleventh Dynasty tomb of Khety at Deir el-Bahri (Rogers Fund, 1923; Rogers Fund, 1926, 26.3.354-5. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Figure 3: Left: A hunting dog accompanies King Tutankhamun on an ostrich hunt as seen on one side of this golden ostrich feather fan from his tomb (Carter no. 242. Image by Siren-Com - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=78095827). Right: An anonymous king spears a lion while his hunting dog assists. This ostracon was found in the debris near the entrance of the tomb of Tomb of Tutankhamun (KV 62), during the Carnarvon/Carter excavations in 1920 (Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926. 26.7.1453. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Egyptian artisans used canine motifs on a variety of objects including figurines, cosmetic items (Figure 4), and board games. Canine imagery appears in the design of the game pieces employed on an ancient Egyptian board game known today as “Hounds and Jackals” (Figure 5). This game needed two players to play. One player chose five dog-headed sticks, while their opponent opted for five jackal-headed ones. The ways in which the animals’ heads are rendered makes the distinction between the two species quite clear. The game board had two sets of twenty-nine holes. The goal was to move one’s figure from a starting point on the board to a designated endpoint. This was one of several board games known from ancient Egypt.

Figure 4: Left: A Middle Kingdom faience figurine of a dog from the site of Lisht (Rogers Fund and Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1924, 24.1.51. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art). Right: A New Kingdom cosmetic vessel in the form of a dog made from bone (Gift of Helen Miller Gould, 1910, 10.130.2520. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Figure 5: A game of Hounds and Jackals with a closeup of two of the game pieces. This gameboard dates to the Middle Kingdom (Edward S. Harkness Gift, 1926 (26.7.1287a-k); Gift of Lord Carnarvon, 2012, 2012.508. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Figure 6: The words for dog in hieroglyphs.

Egyptian artists depicted a variety of different breeds, including sighthounds that resemble modern greyhounds or salukis and smaller, stockier dogs often shown with tightly curled tails. There were two words commonly used for “dog,” tsm and iw (Figure 6). That the Egyptians kept dogs as pets—or as household animals—can be assumed by evidence such as tomb scenes and stelae showing dogs associated with their owners (Figure 7). (Even Egyptian pharaohs kept dogs as pets. A fragmentary stela of King Intef Wahankh II depicts him with three of his dogs standing before him.) Many of these scenes include the names of the dogs depicted.

Over seventy different personal names for dogs are known. The list includes names like Nefer (“Beautiful”) and Hebeny (“Ebony”), which may have referenced the dogs’ appearance. Other names may have described the type of activity the dog did, such as the dog named Meniupu, a name that means, “He is a shepherd.” Other names might tell us more about the dog’s character, such as the dog named Seneb (“Healthy”) or the unfortunately named Adjawetet, whose name meant something like “Useless.”

Figure 7: A small dog can be seen under the chair of the woman on the limestone Funerary Stela of Intef and Senettekh, ca. 2065–2000 (Charles Edwin Wilbour Fund, 54.66. Photo courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum).

Some of these beloved pets were given special burials, such as a dog whose memorial was discovered near the Great Pyramid at the site of Giza in 1935. A carefully inscribed limestone relief was dedicated to its memory (Figure 8). The text describes how the king honored the canine. The text reads:

“The dog which was the guard of His Majesty. Abutiyu is his name. His Majesty ordered that he be buried (ceremonially), that he be given a coffin from the royal treasury, fine linen in great quantity, (and) incense. His Majesty (also) gave perfumed ointment, and (ordered) that a tomb be built for him by the gangs of masons. His Majesty did this for him in order that he (the dog) might be honored (before the great god, Anubis).” (Translation after G. Reisner, BMFA 34 (206), 96–99).

Figure 8: Limestone sunk relief inscription mentioning the dog Abutiu (EMC_JE_67573). Image courtesy of Digital Giza, the Giza Project at Harvard University.

The archaeologist John Garstang found a small inscribed wooden coffin at the site of Beni Hasan. Dating to the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2119–1794 BCE), this burial container was intended for a dog by the name of Heb. The remains of a canine were found inside the coffin (Figure 9). In 1902, W. M. Flinders Petrie found another burial of a dog when he excavated the tomb of a priest named Hapimen at the site of Abydos (Figure 10). The finely wrapped mummified remains of a young dog had been placed alongside the human tomb owner. It seems as if Hapimen wished for his dog to accompany him to the afterlife.

Figure 9: Wooden coffin of a dog (E.47.1902 © The Fitzwilliam Museum, https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/50433).

Figure 10: The mummified dog from the tomb of Hapimen from Abydos (Penn Museum E16219).

Literary texts also give us information about the role of pets in the lives of ancient Egyptians. At the beginning of the New Kingdom tale of The Doomed Prince, we learn that the only child of the Pharaoh was fated at birth to die at the hand of a crocodile, a snake, or a dog. To spare his son this fate, the king locked his son away from all potential dangers. One day, the young boy saw a strange creature from his window and demanded to know what it was. His servant told him that it was a dog. He asked to have one brought to him. The prince’s servant went and told the king and the king agreed to allow a puppy to be brought to his son to make him happy. When the boy grew up, he was tired of being sheltered from his fate and he decided to leave Egypt and face his destiny. He met a princess, fell in love, and told her his story. She insisted that he have his pet dog killed. He adamantly refused, citing his lifelong companionship with the animal since he had raised it since it was a puppy. The tale takes an unexpected twist when one day the prince is out walking alone with his dog. It suddenly turned to him and began to speak. Is his beloved dog the agent of his fate? Will the dog kill him? Unfortunately, the manuscript containing the conclusion of this story has been marred by damage, leaving us in suspense about its ultimate resolution!

This may lead us to ask, was there an ancient Egyptian deity who took the form of a dog? The simple answer is no. It seems that, unlike the case of the goddess Bastet, for example, who could appear in the form of the common house cat (Felis catus), there does not appear to be any Egyptian gods or goddesses who take the form of the domestic dog (Canis familiaris). When we look for Egyptian deities in canid form, we must look to a relative of the dog, namely, the jackal.

There are two ancient Egyptian words translated as “jackal”—one is wnS, and the other is zAb. Both words are determined with the hieroglyphic sign of a standing jackal at the end of the word. We also find this same sign used in the word “dignitary.” We see this sign in the inscription on the Glencairn Museum relief for a man named Ankhemtjenenet, whose nickname was Ineb (Figure 11). He held the important positions of “inspector of scribes” and “secretary of judgements,” which shows that his work related to legal matters. The sunk relief from his tomb shows him alongside his wife, Khenit.

Figure 11: The Sixth Dynasty limestone relief of Ineb and his wife from Tomb D. 201 at Giza (Glencairn Museum E1151).

There are a number of Egyptian gods who appear in what has traditionally been described as a jackal form, or a jackal-headed human form (Figure 12). When these deities take a fully animal form, the animal is canid in nature and has high pointy ears, a pointed snout, an elongated neck, a slender build with long thin legs, and a drooping, club-shaped tail. The most important of these so-called jackal gods are Anubis, Wepwawet, Khenty-amentiu, and Duamutef. While these deities had distinct roles in the Egyptians’ spiritual beliefs, they shared a connection in that they were all funerary deities. The jackal may have been a suitable representation for a funerary deity since the ancient Egyptians had no doubt observed these creatures’ nighttime activities in the desert areas used for cemeteries. (It should, however, be noted that some scholars have raised doubts about whether the animal represented here is in fact a jackal at all. Alternatively, it may be a fusion of various canid species that exhibited shared natural animal behaviors that were appropriate for a deity who interacted with the recently deceased and buried. The Egyptians did have other composite deities such as Taweret and Ammit, as well as deities whose animal form is ambiguous like that of the god Seth. For simplicity’s sake, we will continue to refer to these deities as jackal gods.)

Figure 12: List of Egyptian gods who take the form of a jackal.

Anubis

The best known of Egypt’s jackal deities is Anubis. He usually appears in the form of a black jackal. There are several depictions of Anubis in fully jackal form on view in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery. A pair of jackals can be seen on the top of the New Kingdom stele of Maienhekau (Figure 13), another pair can be seen at the foot of the coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis (Figure 14), and a single preserved jackal adorns a fragment of a linen funerary shroud (Figure 15). On the shroud, the jackal, resting atop a shrine, wears a collar and holds a scepter in its paws, while a flail hovers above its back. Anubis can also be depicted as a jackal-headed man (Figure 16).

Figure 13: A pair of jackals on the stela of Maienhekau (Glencairn Museum E1266).

Figure 14: A jackal, one of a pair, on the foot of the coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis (Glencairn Museum E1267).

Figure 15: Anubis, the god of the dead and embalming, is represented as a jackal-like animal on this linen burial shroud fragment (Glencairn Museum E1115).

Figure 16: Figurines of Anubis in the Glencairn Museum collection.

Anubis is an important funerary deity, and prayers of offering for the deceased commonly invoke him. He was the god of embalming who tended to the deceased’s mummy, watched over the scale at the final judgment, and brought the deceased before Osiris. A diorama in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery, based on the funerary papyrus of a woman named Isty, illustrates this role nicely (Figure 17). Anubis, shown as a jackal-headed man, brings the deceased for her final judgement. In the next scene, Isty’s heart is weighed against a feather, which represented the concept of ma’at (“truth” or “balance”). For Isty to pass successfully into the afterlife, her heart must be equal in weight to the feather. Anubis oversees the weighing of her heart while the devouring demon Ammit waits to gobble up any heart considered unfit. The divine scribe, Thoth, records the successful verdict. Isty’s heart is judged worthy, and she is brought before Osiris and granted access to the afterlife.

Figure 17: A view of a diorama in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery based on the Twenty-First Dynasty Book of the Dead Papyrus of a woman named Isty.

One of Anubis’s significant roles was as the divine embalmer. Tomb scenes show Anubis tending to the wrapped and mummified body of the deceased on the funerary bier. Anubis is also shown participating in the ritual known as the “Opening of the Mouth” on funerary stelae and on funerary papyri. The purpose of this rite was the restoration of function to the mummified individual’s mouth, nose, eyes, and ears. This insured that the deceased would be capable of speech, sight, hearing, eating, and other important bodily functions in the afterlife (Figure 18). In reality, these rites were conducted by ancient Egyptian priests filling the role of the god Anubis. Intriguing evidence points to the fact that, in some instances, these mortuary priests may have worn jackal masks to further enhance their identification with this god. A couple of examples of masks of this type have been found (Figure 19). The diorama of the embalming house in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery features figures of embalming priests, one of whom wears a mask much like these ancient examples (Figure 20).

Figure 18: Left: Anubis attends to the mummy of Sennedjem from a scene on the wall of his tomb. Right: The Opening of the Mouth ritual is performed on the mummy of the deceased. This image comes from the Book of the Dead papyrus of a woman named Hunefer.

Figure 19: Left: A cartonnage mask in the form of the Anubis. Image courtesy of Courtesy of Harrogate Museums and Arts. Right: An Anubis mask made of ceramic (IN1585, Roemer-Pelizaeus Museum, Hildesheim).

Figure 20: A view of the embalming house diorama in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery showing an embalming priest wearing an Anubis mask while carrying out some of the rituals associated with the mummification process.

One of Anubis’s epithets was “one who is upon his mountain,” perhaps referring to the high desert cliffs which surround the location of many of Egypt’s ancient cemeteries. Anubis was seen as a guardian and protector of the necropolis and of the dead buried therein. During the New Kingdom, the necropolis seals for the royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings had a depiction of Anubis placed above images of Egypt’s defeated enemies. These enemies were seen as embodiments of chaos that posed a threat to the eternal rest of the pharaohs buried in the Valley of the Kings. By placing Anubis as their conqueror, he exerted a magical control, thus safeguarding the kings and their burial places.

Figure 21: A mummified jackal with linen wrappings (British Museum EA6743 © The Trustees of the British Museum).

Above, mention was made of examples of seemingly beloved canines who were mummified and given special burials near their owners. There is another category of canid mummies that is even more common—votive mummies (Figure 21). Animal mummies of this kind were created with the purpose of being dedicated to a particular deity by a devout pilgrim in gratitude for an answered prayer, as an offering made in conjunction with a request, or as a commemoration of a visit to a patron deity’s shrine. Vast animal cemeteries, or catacombs, are known throughout Egypt. At the site of Saqqara, for example, recent excavations have uncovered two sizeable catacombs dedicated to Anubis. The researchers working at this site estimate that these burial places were in use for hundreds of years and, over this long span of time, may have been the repository for millions of canine votive burials in honor of Anubis.

Anubis retained his importance well into the Greco-Roman period. His worship extended outside of Egypt. For example, his image appears on wall paintings at Pompeii and Herculaneum. The classical authors described Anubis’ origin as the result of an affair between Osiris and Nephthys. After Anubis was born, Nephthys abandoned him, but wild dogs led Isis to the child, and she raised him as her own and he became her protector. Anubis is also mentioned in classical texts as one who helped Isis during her search for Osiris after he had been killed and dismembered by Seth.

Wepwawet

Wepwawet's name means “the opener of the ways,” signifying his role in leading the deceased through the paths of the underworld. In New Kingdom funerary texts, such as the Book of Going Forth by Day (also known as the Book of the Dead) and the Book of That Which Is in the Underworld (the Amduat), Wepwawet is a protective deity. In royal mythology, a fast, doglike creature accompanies the king while hunting, an animal that is referred to as the “the one with the sharp arrow who is more powerful than the gods.” These arrows also “opened the way,” and may be connected to the name of this deity.

Wepwawet often appears atop a standard. His image is usually accompanied by a uraeus and an enigmatic hieroglyph, which has been proposed to be a representation of the royal placenta. The standard of Wepwawet was carried preceding the king in processions (Figure 22). This use of the god's image on a standard may show his early role as a warlike deity. He is sometimes referred to as a son of Isis and has close connections with the deities Harendotes, a falcon deity whose name meant “Horus, protector of his father,” and the ram god Herishef.

Figure 22: On this ivory label the standard of Wepwawet can be seen on the right (British Museum EA55586 © The Trustees of the British Museum).

Khenty-amentiu

Khenty-amentiu was an early mortuary deity who protected the area of the royal cemetery at Abydos. He took the form of a recumbent jackal and is attested as early as the First Dynasty. His name means “Foremost of the Westerners.” For the ancient Egyptians, the “west” was the location of the dead. Over time, the importance of the god Osiris and his cult at Abydos overshadowed that of Khenty-amentiu, and eventually this god’s name becomes one of the epithets of Osiris (and of Anubis) (Figure 23).

Figure 23: A couple is shown worshipping Osiris, Isis, Nephthys, and the four sons of Horus on a painted wooden stela. In the funerary prayer below, Osiris is mentioned, and in the highlighted area he is referred to with the epithet Khenty-amentiu the “Foremost of the Westerners” (Penn Museum 29-86-422).

Duamutef

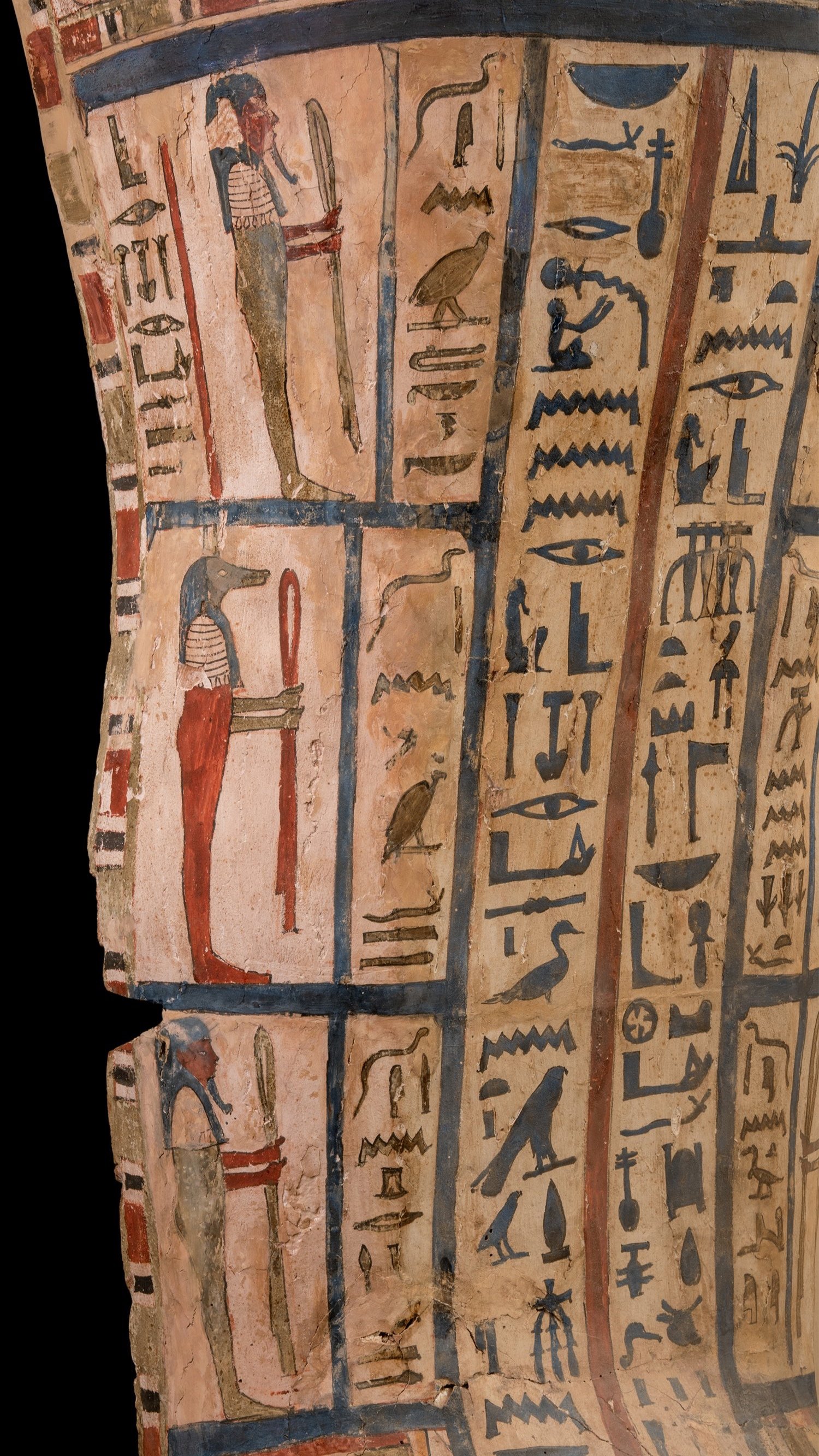

During the mummification process, embalming priests removed the internal organs and mummified them separately. The embalmers then placed the wrapped organs in four canopic jars. Each jar had a lid in the form of the head of a different god (Figure 24). These gods were the four sons of Horus, and they protected the deceased’s internal organs: human-headed Imsety guarded the liver, baboon-headed Hapi the lungs, hawk-headed Qebehsenuef the intestines, and jackal-headed Duamutef the stomach (see lead photo, top). In addition to appearing on canopic jars, the four sons of Horus were popular motifs on coffins and funerary stelae. In Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery, images of these four gods adorn the painted wooden coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis. The figure of Duamutef is on the proper right in the second register (Figure 25). Amulets of the four sons of Horus became common on funerary equipment during the Late Period; a set of them is on exhibit in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery (Figure 26).

Figure 24: The four sons of Horus can be seen on the stela of the Lady of the House, Tabiemmut. They stand behind the goddess Isis and the god Re-Horakhty as Tabiemmut raises her hands in adoration before this group of deities (Rogers Fund, 1927. Accession Number: 27.2.5, image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Figure 25: View of Duamutef of the coffin of Sema-tawy-iirdis (Glencairn Museum, E1267).

Figure 26: A set of faience amulets of the four sons of Horus in Glencairn’s Egyptian gallery. Amulets of this type were typically placed upon the linen wrappings that surrounded the mummified body of the deceased.

Figure 27: Here, Kufta, the “dig dog,” carefully guards the backpack of Dr. Joe Wegner, the director of the Penn Museum’s excavations at South Abydos.

Even today in Egypt, Egyptologists find a close connection between dogs and humans. Often, while excavating at the site of Abydos in southern Egypt, a local canine resident adopts our expedition members during archaeological work (Figure 27). Most recently, a friendly puppy named Kufta—who has grown much bigger over the past several seasons—joined our excavation team. Just like her ancient ancestors, she serves as a watchdog and helps to guard the site from unwelcome visitors.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Curator, Egyptian Section

Penn Museum

Select Bibliography

Brewer, Douglas, Terence Clark, and Adrian Phillips 2001. Dogs in antiquity—Anubis to Cerberus: the origins of the domestic dog. Warminster: Aris & Phillips.

Dodson, Aidan 2001. “Four Sons of Horus.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

Doxey, Denise 2001. “Anubis.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

Evans, Linda 2008. “The Anubis animal: a behavioural solution?” Göttinger Miszellen 216, 17–24.

Fischer, Henry G. 1977. “More ancient Egyptian names of dogs and other animals,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 12, 173–178.

Fischer, Henry G. 1980. “More ancient Egyptian names of dogs and other animals,” In Anonymous (ed.), Ancient Egypt in the Metropolitan Museum Journal, supplement 12–13 (1977–1978) New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Griffith, Christina 2018. “Dogs and cats and birds, oh my! The Penn Museum’s Egyptian animal mummies,” Expedition 60 (3), 23-25.

Houlihan, Patrick F. 1996. The animal world of the pharaohs. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press.

Houser-Wegner, Jennifer 2001. “Wepwawet.” In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

Ikram, Salima 2013. “Man's best friend for eternity: dog and human burials in ancient Egypt,” Anthropozoologica 48 (2), 299–307.

Ikram, Salima and Paul Nicholson 2018. “Sacred animal cults in Egypt: excavating the catacombs of Anubis at Saqqara.” Expedition 60 (3), 12–22.

Kitagawa, Chiori 2013. “Tomb of the dogs in Gebel Asyut al-gharbi (Middle Egypt, Late to Ptolemaic/Roman Period): preliminary results on the canid remains’” In De Cupere, Bea, Veerle Linseele, and Sheila Hamilton-Dyer (eds), Archaeozoology of the Near East X: Proceedings of the Tenth International Symposium on the archaeozoology of South-Western Asia and adjacent areas, 343–356. Leuven: Peeters.

Lichtheim, Miriam 2006. Ancient Egyptian literature. A book of readings, volume II: The New Kingdom. Berkeley, CA; London: University of California Press.

Nicholson, Paul T., Salima Ikram, and Steve Mills 2015. “The catacombs of Anubis at North Saqqara,” Antiquity 89 (345), 645–661.

Reisner, George A. 1936. “The dog which was honored by the king of Upper and Lower Egypt,” Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts 34 (206), 96-99.

Saied, Ahmed M. 2003. “Chontiamenti oder Anubis,” In Hawass, Zahi and Lyla Pinch Brock (eds), Egyptology at the dawn of the twenty-first century: proceedings of the Eighth International Congress of Egyptologists, Cairo, 2000 2, 474–477. Cairo; New York: American University in Cairo Press.

Tooley, Angela M. J. 1988. “Coffin of a dog from Beni Hasan,” Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 74, 207–211.

Pouls Wegner, Mary-Ann 2007. “Wepwawet in context: a reconsideration of the jackal deity and its role in the spatial organization of the north Abydos landscape,” Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 43, 139–150.

Wilfong, T. G. 2015. Death dogs: the jackal gods of ancient Egypt. Kelsey Museum Publication 11. Ann Arbor: Kelsey Museum of Archaeology.

Wyatt, John 2020. “Anubis: jackal, wolf, dog, fox or hyena?,” Ancient Egypt: the history, people and culture of the Nile valley 119 (20/5), 44–51.

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox (12 times per year)? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.