Glencairn Museum News | Number 3, 2025

This lamp was given to Ariel Gunther after 50 years of service to Bryn Athyn Cathedral. Gunther (right) was in charge of constructing glass furnaces, the chemical composition of the glass batches, and the overall supervision of the factory that made stained glass for both the Cathedral and Glencairn. David Smith (left), the primary glassblower, came to Bryn Athyn in 1922. He was 78 years old when he blew his last batch of Bryn Athyn glass in 1942.

Childhood and Education

Ariel C. Gunther (1903–1993), known to his friends as Gunny, was born in Baltimore in 1903. His father, a German-born sheet-metal worker, and his mother, the daughter of garment workers, met at a Swedenborgian church in the city. The Baltimore of Gunther’s early childhood was a bustling industrial boomtown, and his recollections of the place reflect the strong impact the ever-present thrum of workers and machinery made on him. In the summer of 1910, the Gunther family relocated to decidedly quieter environs, purchasing an undeveloped tract of land in Arbutus, Maryland, with a small group of their fellow Baltimore congregants. There, the community engaged in their own kind of enterprise, developing the property from the ground up, beginning with a small chapel to serve the congregation.

Figure 1: Ariel Gunther (middle row, far right) with his first grade class at a public school in Baltimore, Maryland.

Figure 2: The chapel of the Arbutus Circle of the General Church, built in 1910.

Figure 3: Ariel Gunther (top) and other beneficiaries of the Academy of the New Church’s work-study scholarship program. Gunther worked in the dining hall throughout much of his high school career.

The local school ended in the eighth grade, and the family couldn’t afford train fare to Baltimore for high school. So, at just 14, Gunther entered the workforce, taking a job as a warehouse boy in a sheet metal factory. In the summer of 1918, however, he was offered the opportunity to apply for a scholarship to attend the Academy of the New Church in Bryn Athyn. It was there that he would complete his education, graduating in 1922 as valedictorian and earning the school’s prestigious Phi Alpha Upsilon medal, awarded for “Good scholarship, good conduct, good character and general development, and, in brief, all the qualities that make a good and loyal student” (The Bulletin. Vol. XIV, no. 5, Feb. 1926, p. 129. Sons of the Academy of the New Church).

Gunther’s record of academic excellence and leadership within the Academy brought him to the attention of Raymond Pitcairn, whose grand plans for Bryn Athyn Cathedral included the creation of stained-glass windows and mosaics that could rival those of medieval Europe. In pursuit of this goal, Pitcairn had been searching for a young apprentice to train under John Larson, a New York-based glassmaker with whom Pitcairn had been working since the mid-1910s. According to Gunther’s autobiography, the offer came with an extraordinary stipulation: the 19-year-old, not yet graduated from high school, was only to take the position if he should intend to make it his life’s work. Gunther began at the glassworks shortly thereafter, officially commencing his decades-long career in late June of 1922.

Figure 4: Academy of the New Church graduating class of 1922. Gunther is the furthest left in the middle row.

Apprenticeship at the Glassworks

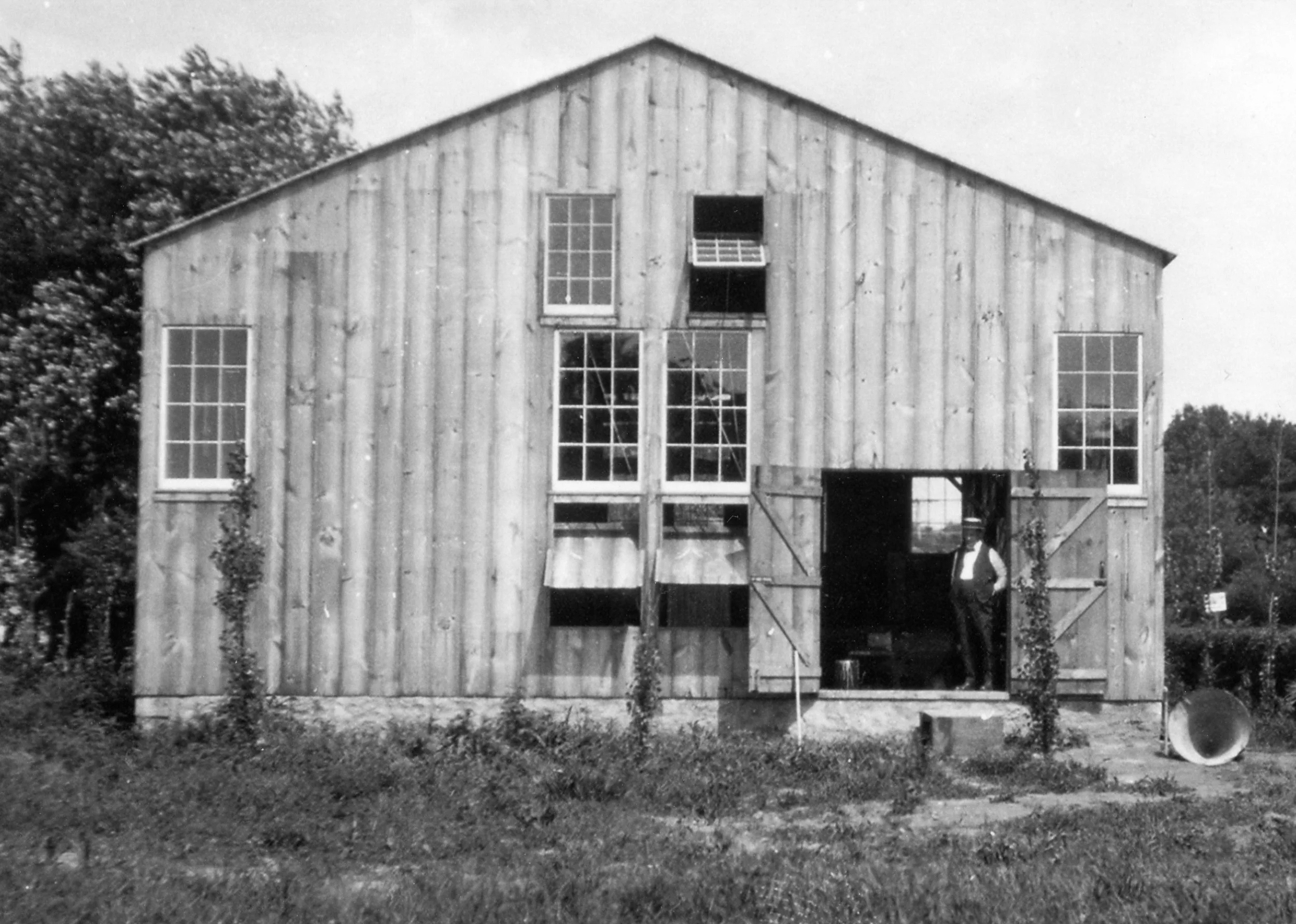

The Bryn Athyn Glass Factory, as it was known locally, was built in 1922 and was initially supplied with equipment from Larson’s New York operation. Gunther’s responsibilities in these early days were various; collecting broken milk bottles (melted down and used to glaze the furnace); kneading clay with his feet to make crucibles—vessels used to melt glass; and lighting the furnaces daily at quarter to six in the morning to ready them for use by Larson and David Smith, the factory’s principal glassblower. Gunther also aided Larson with the development and construction of furnaces and equipment more specifically tailored to the project’s unique requirements. Larson had already begun the difficult work of developing the formulas for different shades of pot-metal glass—so called because the color is fused into the molten batch, rather than applied as a surface stain.

Figure 5: David Smith standing in the doorway of the Bryn Athyn Glassworks.

As specific recipes for medieval glass were regarded as trade secrets, very few survived to inform Larson’s experiments. But Larson, coming from a family of glassworkers, was experienced and, thanks to Pitcairn, had the opportunity to study authentic medieval glass firsthand by visiting famed collections such as that of Henry C. Lawrence, from whom Pitcairn purchased many of his finest acquisitions. His experimentation was fruitful, resulting in a substantial stock of colored glass and a diverse roster of formulas that would serve as the basis for all the stained glass made in the Bryn Athyn glassworks in the decades to come. Unlike Larson and Smith, Gunther had no prior knowledge of glassmaking. Nevertheless, in 1925, when Larson was dismissed, and after less than three years as an apprentice, Pitcairn entrusted the glassworks to Gunther’s leadership.

Figure 6: Crucibles (or pots) from the Bryn Athyn glassworks in which the metal oxides would be combined with the molten glass. They have been preserved and are in storage at Glencain Museum.

Figure 7: Various glassmaking equipment and stained-glass pieces from the Bryn Athyn glassworks in storage at Glencain Museum.

The Ruby Glass

One of the first tasks Pitcairn assigned to Gunther was to finalize a working formula for the striated, or streaky, ruby glass typical of medieval windows. While Larson had already attained a similar hue, there were, according to Gunther, still a number of shortcomings that made it unsuitable for the final windows. Indeed, experimentation continued with most of the shades, and despite the vast quantity of glass sheets stockpiled during Larson’s tenure, it is possible that very little of Larson’s glass made its way into the buildings. Gunther himself estimated that less than 15% of the glass at the Cathedral and virtually none of that at Glencairn came from the glassworks’ first efforts, with the majority of the remaining sheets ultimately being sold to the studio of another glass artist in the 1920s. Though these numbers are impossible to verify, in his nearly two decades as manager of the glassworks, Gunther must have contributed a significant proportion of the present glass, mixing the batches and operating the furnaces while Smith, who stayed on after Larson’s departure, blew it into sheets and roundels.

Figure 8: A 13th-century panel (Glencairn Museum 03.SG.43) from the Church of Sainte-Radegonde in France showcasing authentic medieval striated ruby glass.

Figure 9: Mary with Christ Child window in Glencairn’s Great Hall, made with Bryn Athyn striated ruby glass.

Figure 10: Ariel Gunther mixing the ingredients for a batch of glass.

Others involved in the operation have also corroborated Gunther’s involvement in the development of the ruby glass. Lawrence Saint, who worked as a stained-glass artist at the Cathedral (and later headed the stained-glass division at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C.), described the difference between Larson’s and Gunther’s formulas in his book, The Romance of Stained Glass. In the mid-1920s, Saint was sent by Pitcairn on a research trip to Europe, from which he returned with some small fragments of medieval ruby glass from Chartres Cathedral to compare with Larson’s: “I pointed out that besides the streaks there was another subtlety to the wonder of the old reds for there was a pale greenish layer on the back. I knew practically nothing about glass-making and was surprised to see how quickly Mr. Gunther, one of Mr. Pitcairn’s own church people who now had charge of the glass house, was able to add the subtle greenish layer.” Of Gunther, Saint wrote, “He is very clever, brilliant, ingenious, and resourceful,” adding that his ruby glass “was of the same general structure as the old, had gained in richness, and fired well” (Lawrence Saint, The Romance of Stained Glass: A Story of His Experiences and Experiments, 1959, p. 10).

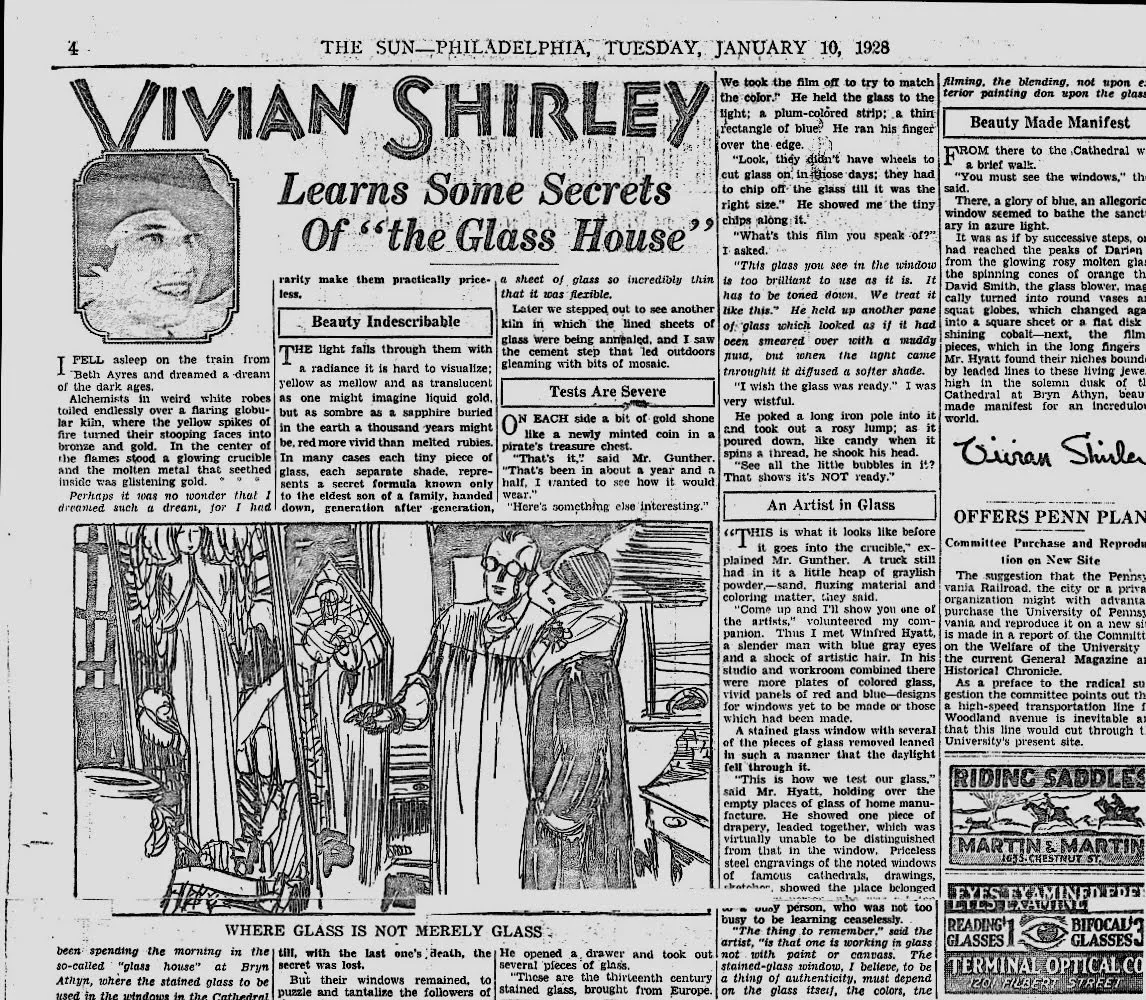

Figure 11: Newspaper clipping from the Philadelphia Sun for which Ariel Gunther and Winfred Hyatt were interviewed in 1928. Gunther is drawn showing interviewer Vivian Shirley around the Glass Studio.

Figure 12: A mosaic panel depicting scenes from the life of Moses from the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, 432–440, one of the churches Albert Cullen was tasked with visiting for the purpose of making copies.

The Mosaics

Gunther’s next charge was to devise a formula for mosaic glass. Pitcairn admired the composition, colors, and matte finish of 5th- and 6th-century examples from Italy, especially those in Ravenna. He considered modern mosaics too glossy in comparison. Pitcairn had hired an English artist, Albert Cullen, to paint full-size copies of some of the finest early medieval mosaics in Europe, sending him throughout Italy, France, and his native England to encounter the mosaics in situ.

Though experimentation had begun even in Larson’s time, it wasn’t until 1927 that meaningful progress was made on the formula for the mosaic glass. In January of that year, Smith, the glassblower, fell ill. His six-week absence brought all glass production to a halt. In the meantime, Gunther turned to the sizable collection of literature Pitcairn had been amassing on the subject of stained glass. In a translation of an old German manuscript, a manual of sorts on the production of different types of glass, Gunther found a clue in the form of a warning from the manuscript’s author: Add too much of a certain substance (likely lime) and the glass becomes like stone, nearly impossible to work and very dull and rough.

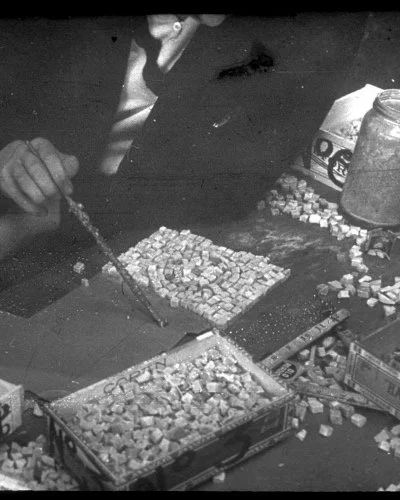

Gunther fired the first batch of this glass the very next morning. It was not yet of the correct consistency to be cast and cut into individual pieces (called tesserae), so Gunther continued to experiment until the correct proportion was found—low enough that the glass was workable but high enough that it retained its matte quality. Because the colors of pot-metal glass rely on certain chemical interactions between metal oxides and the base glass, entirely new color formulas had to be devised for the mosaic glass, which had a different composition from the stained glass. Over the next twelve months, Gunther finalized the formulas for most of the principal shades that would be used in the mosaics at Glencairn. In November of 1927, Pitcairn instructed Gunther to pack up a box of sample tesserae in each of these shades to send to Cullen in Europe.

Figure 13: Albert Cullen at work assembling mosaics at Glencairn.

Cullen was thrilled with the results. He and Pitcairn agreed that it would be instructive to have Gunther join Cullen overseas to experience firsthand the remarkable effect of the old mosaics and stained-glass windows. Gunther was to travel on January 17, 1928, and his tour was to include Naples, Rome, Florence, Ravenna, and Venice in Italy, Paris and Chartres in France, Berlin in Germany (to visit the factory of the Ravenna Glass Company, which produced many of the mosaics at the Cathedral Basilica of Saint Louis in St. Louis, Missouri), and Canterbury in England. Just before he was set to travel, however, Pitcairn received notice that Lawrence Saint was leaving Bryn Athyn to work on the National Cathedral. Needing an artist to replace him, Pitcairn arranged for Cullen to be moved to the United States and cancelled Gunther’s trip.

When Cullen arrived in October of 1928, he brought with him modern mosaic tesserae color-matched to the compositions Gunther would have encountered had his European tour taken place. Using these as exemplars, Gunther was able to develop the last of the formulas for colored mosaic glass, ultimately producing a complete range of shades which, according to those involved, numbered in the thousands. Only one color remained to be worked out. Gold tesserae were not created by coloring the molten glass, but by sandwiching real gold leaf between two thin sheets of clear glass—a process Gunther would perfect in the subsequent months.

Figure 14: Mosaic roundel from Glencairn’s entryway showing the wide range of shades used.

Figure 15: A medallion representing Bryn Athyn College from the Academy seal featured in Glencairn’s Great Hall. The temple building sits in a field of golden mosaic tesserae.

Pitcairn was extremely satisfied with the results of Gunther’s experimentation, later writing, “the glass for the mosaic we are producing in our own studios . . . is, I believe, the finest material which has been produced for mosaic in modern times” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to A. Cimarosti. 10 November 1931). Soon after, the first mosaic designs were drawn up by Winfred Hyatt and Robert Glenn, Pitcairn’s nephew, ready to be rendered in glass. In one of his lectures, Gunther described the process of producing the tesserae once the formula was mixed and the batch was melted:

“We cast this onto a piece of very smooth cast iron, and then I made this rolling pin out of a piece of three-inch pipe, and I rolled it out into an uneven pancake, about 3/8 of an inch thick. This was then annealed, and then it had to be cut up into these small tesserae for the mosaic work” (Ariel Gunther, Lecture Transcript).

Figure 16: Ariel Gunther rolling out a slab of mosaic glass.

Gunther was involved at every stage of this process, solving problems as they arose. One such problem was the adhesive used to set the tesserae onto the paper patterns marking the final designs. The solution came about almost by chance when one of Gunther’s assistants brought in a bag of gumdrops. Suddenly inspired, Gunther asked another worker, who had previously been in the candy trade, which ingredients were used to help gumdrops and jellybeans maintain their gummy texture rather than hardening (the unfortunate fate of his earlier glue recipes). Those ingredients—gelatin, glycerin, and gum arabic—mixed with water, formed the ideal glue for mounting the tesserae.

Figure 17: An assistant cutting mosaic tesserae.

Figure 18: An assistant setting mosaic tesserae onto a paper pattern. The jar on his left contains the mosaic adhesive.

Gunther worked alongside Cullen, Glenn, and Hyatt to achieve the correct shading and gradation of color called for in Glenn’s and Hyatt’s designs, spending countless hours arranging and rearranging individual tesserae until the desired effect was achieved. He and Cullen also directed the installation of the mosaics, devising strategies according to the unique constraints of the rooms for which the mosaics were intended. Each mosaic composition, from first sketch to final product, took a year or more to complete. The work was deeply collaborative, and it is thus difficult to pinpoint where one person’s contribution ended and another’s began. Still, Gunther left his mark on the Cathedral and, especially, on Glencairn, each mosaic glass tessera and stained-glass window speaking to years of ingenuity and dedicated labor.

Figure 19: The ceiling of the Great Hall with scaffolding. The mosaics were precast into cement slabs and then bolted to the steel trusses supporting the weight of the ceiling.

Figure 20: The ceiling of Glencairn’s chapel. Pitcairn believed the image would only read correctly if the mosaic tesserae ran almost parallel to the floor, but Gunther and his team decided to press the tesserae into a clay slab at an angle. Their decision might have been influenced by a French document that Cullen consulted during his research trip for Pitcairn. These slabs were set into place in a wooden frame and concrete was poured on top, encapsulating the clay.

The Closure of the Glassworks

Though there were plans for further work on the Cathedral, including the possibility of specially designed mosaics, the issuing of Order L-41 by the War Production Board in 1942 forbade all non-essential construction projects so as not to divert materials and labor away from the war effort. The glassworks closed in April of that year and, ten years later, it was demolished. Gunther, now out of work, returned to the sheet metal business. He had first-hand experience with planes, having worked part-time in the 1920s with Harold Pitcairn (Raymond’s brother) at his aircraft shop in Bryn Athyn in exchange for flying lessons. He earned his pilot’s license, signed by Orville Wright himself, in 1925.

Figure 21: Ariel Gunther’s pilot’s license, issued October 22, 1925.

This unique combination of skills and qualifications helped him secure a position at Bendix Aviation, where he worked until late December, 1945. That year, Raymond Pitcairn requested that he return to work at the Cathedral in the capacity of supervisor of the mechanical maintenance of the building and of any further building projects which might be undertaken there. Over the next several decades, Gunther would wear a range of different hats, even acting as temporary curator of the Cathedral’s collections and archives. Though Gunther yearned to return to the stained glass and mosaics to which he had long been committed, he carried out his various responsibilities with characteristic zeal, making himself useful wherever he was needed.

Figure 22: Ariel Gunther and his wife Agnes.

In 1963, members of the Bryn Athyn community put funds together to help Gunther fulfill a long-delayed dream, contributing over $1,200 to send him and his wife Agnes on the trip he had been set to go on some 35 years prior. On their travels through Europe, Gunther brought along a series of slides he had prepared as part of an illustrated lecture on the history of Bryn Athyn Cathedral and on the making of stained glass and mosaics in Bryn Athyn. This marked the first of many such lectures given throughout Gunther’s lifetime. One of these was recorded, and the audio is still available through Glencairn Museum’s digital archives, allowing us to experience Gunther’s presentation as it was given decades ago.

Gunther retired in his 70s, though he continued to perform one Cathedral-related job even into his 80s. Every year at Christmastime, Gunther would climb a narrow spiral staircase 150 feet up to the top of Bryn Athyn Cathedral to place the Christmas star, a responsibility he undertook for over 60 years. When, in 1982, Gunther suffered a medical episode at the pinnacle of the Cathedral’s tower, leaving him stranded for over two hours while a rescue plan could be worked out, Mason Adams, Bryn Athyn’s police chief, predicted, “I’m sure he’ll be alright. He’s as tough as nails” (“An Elderly Man Who Has Placed a Christmas Star. . .” UPI Archives, 13 Dec. 1984). As to why an elderly Gunther would go to such lengths to carry out this task, Adams explained, “That’s his job, it’s his duty, I guess he feels.” Gunther’s sense of duty and love for his community defined his life and legacy, and nowhere is his devotion more visible than at Glencairn and Bryn Athyn Cathedral. He considered these buildings great works of art, having been, in his estimation, “produced by men having a deep religious motivation in their work. . . Any man,” according to Gunther, “is greatly blessed if he may have but a small part in such great works” (Opportunity, Challenge, and Privilege, p. 152).

Talia Regan

Guide and educator, Glencairn Museum