Glencairn Museum News | Number 3, 2023

Detail of the vignette on the mummy bandage of Padiwesir, which was created using black ink. The deceased is standing on the right-hand side, holding a staff. Behind him is an offering stand with loaves of bread and a lotus blossom. On the far left is an image of a goddess within a shrine. This artifact is on exhibit in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian gallery (E1270).

In a previous article in Glencairn Museum News, Preparations for a Good Burial: Funerary Art in Glencairn’s Ancient Egyptian Gallery, we examined items considered essential to a successful afterlife, including objects of daily life such as furniture, clothing, foodstuffs, jewelry, and weaponry, as well as objects specifically made for the burial such as coffins, canopic jars, funerary figurines, amulets, and other tomb goods. Here we will examine another crucial element for the protection of the deceased after death—funerary literature that was created to magically protect the deceased on their journey to the afterlife. The Glencairn Museum collection has a fragment of a decorated linen mummy wrapping inscribed with spells from the corpus of funerary literature known as the Book of the Dead. Before we explore the spells on this particular mummy wrapping, we will look at the origins of funerary spells in ancient Egypt and the ways in which the Egyptians incorporated these texts into their burial equipment (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Fragment of a linen mummy wrapping inscribed in hieratic with spells from the Book of the Dead. Glencairn Museum E1270.

Ancient Egyptian funerary literature

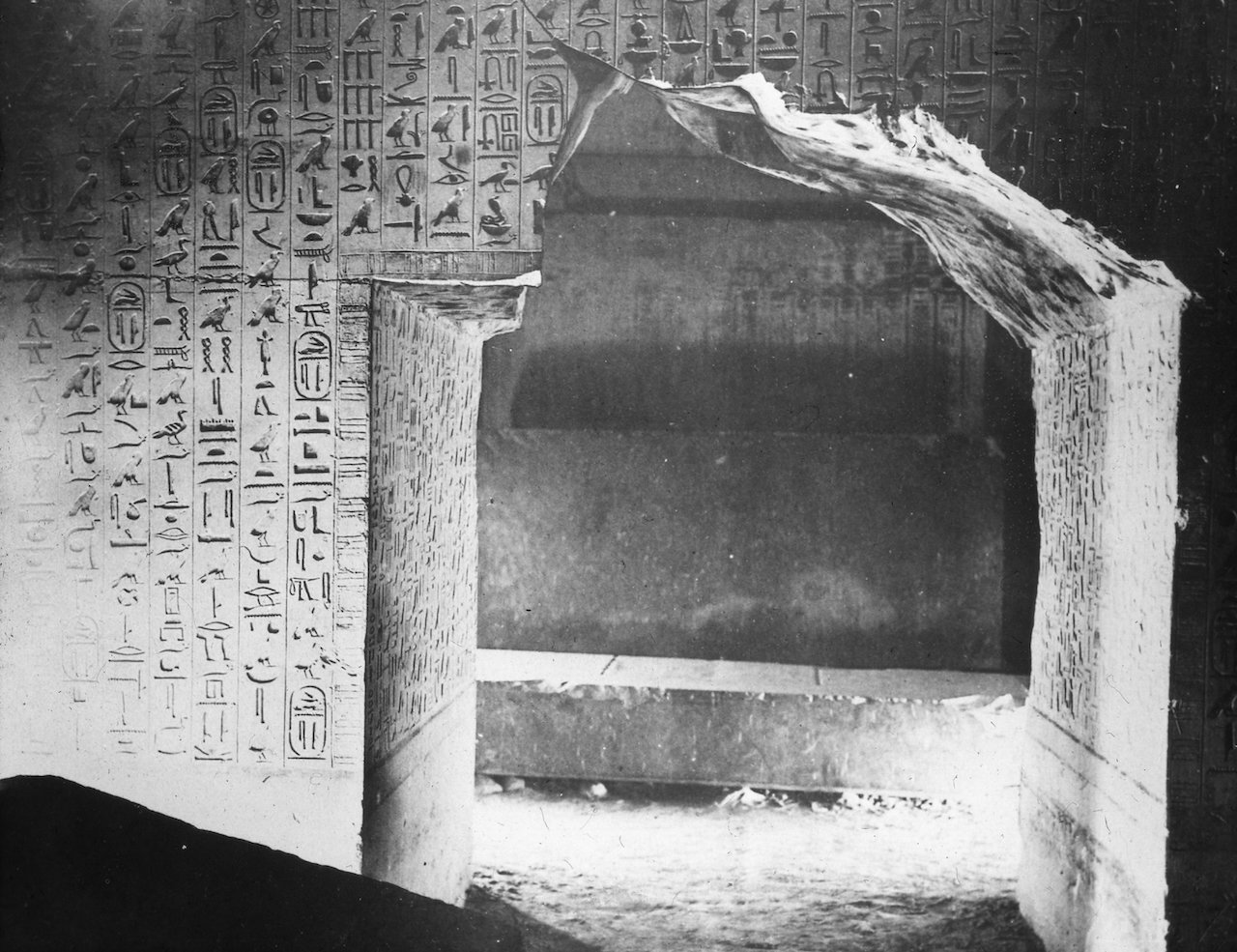

The ancient Egyptians had an extensive body of funerary literature composed for the purpose of protecting the deceased and ensuring their successful passage to the afterlife. The earliest corpus of Egyptian funerary literature is known as the Pyramid Texts. These spells seem to have been composed in the Old Kingdom (2625–2130 BCE) and were originally carved in hieroglyphs on the walls of the underground chambers of the pyramids of kings and queens (Figure 2). The earliest examples date to the end of the Fifth Dynasty (2500–2350 BCE) and are found in royal pyramids at the site of Saqqara. At this time, these funerary texts were reserved for royalty, and they continued in use in royal burials until the First Intermediate Period. Altogether there are close to 800 Pyramid Text spells, but no single Old Kingdom pyramid contains all the spells. The goal of the spells in the Pyramid Texts was to assist the deceased in their transformation into an effective spirit that could ascend into the sky and dwell in the company of the gods. Other Pyramid Text spells concern the protection of the deceased’s body and safeguarding their burial place.

Figure 2: View of Pyramid Texts carved on the walls of one of the subterranean chambers of the pyramid of King Unas at the site of Saqqara, Egypt.

Figure 3: Exterior of the Twelfth Dynasty painted wooden coffin of Seni with lid (EA30842) discovered at the site of Bersheh, Egypt. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

A second important collection of funerary spells is known as the Coffin Texts. As their name implies, these texts were usually found inscribed on the coffin of the deceased (Figures 3 and 4). These texts come into use in the First Intermediate Period (2130–1980 BCE), and they do share some similarities with the Pyramid Texts. Some of the Coffin Texts spells were clearly modeled on Pyramid Text spells, but there are numerous new spells in this corpus with close to 1,200 individual spells identified as Coffin Texts. While the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom were reserved for royalty, the Coffin Texts were accessible to non-royal people. Most known examples of Coffin Texts are found on coffins of the Middle Kingdom (1980–1630 BCE), but Coffin Texts could also appear on tomb walls and ceilings, stelae, canopic chests, papyri, and mummy masks. The Coffin Texts aided the deceased as they journeyed towards Osiris and eternal life. The spells place emphasis on the god Osiris, the ruler of the afterlife who dwells in a place the Egyptians called the Duat (Figure 5). These texts describe the realm of the dead and the many dangerous challenges the deceased must face as they make their way through this underworld realm.

Figure 4: View of the interior of the coffin of Seni showing Coffin Text spells inscribed in ink (EA30842). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 5: Bronze figure of the god Osiris (Glencairn Museum E74).

By the beginning of the New Kingdom (1539–1075 BCE), a new type of funerary text was in use by the ancient Egyptians. This corpus of spells was influenced by—and similar to—the earlier Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts and is referred to as the Book of the Dead. This is a modern name for a collection of almost two hundred funerary spells that were meant to facilitate the deceased’s passage to the afterlife. In contrast to the Pyramid Texts and the Coffin Texts, the spells in the Book of the Dead had a remarkably long lifespan. They were in use for almost 2,000 years, from their first appearance around 1,500 BCE to the last attested copies of the spells in the early centuries CE. The modern name for these texts was coined in the 1800s by the Egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius, who described these spells using the German term Totenbuch, which is translated into English as “Book of the Dead.” The original ancient Egyptian name for these spells is rw nw prt m hrw (Figure 6), or “Spells (or utterances) for Coming Forth by Day,” an idea that references a wish that the deceased (or their ka, or “life force”) would be able to leave the darkness of the tomb and participate in an afterlife.

Figure 6: The hieroglyphs for the ancient Egyptian name for the corpus of funerary spells known as the Book of the Dead.

Figure 7: Book of the Dead spells can be found on a variety of funerary objects. Here is an example of an amulet in the form of a papyrus column inscribed with a spell from the Book of the Dead. Image courtesy of the Penn Museum (E13413).

Each Book of the Dead spell was given a number by modern scholars to identify and catalog the individual compositions. Beginning in 1842, Lepsius identified and numbered 165 spells. Later scholars such as Édouard Naville, E. A. Wallis Budge, and Willem Pleyte added additional spells to the corpus. While the number of spells that comprise the Book of the Dead totals around 200, no single example of a Book of the Dead contains all 200 spells. It should be noted that the term “book” is also misleading as none of the Egyptian Books of the Dead take the form of a modern book, or codex. Rather, these spells are typically found on papyri, originally produced in scroll form. In keeping with the modern concept of a book, Egyptologists often refer to the individual spell’s number as its “chapter” number. Book of the Dead spells can also be found on other funerary equipment, such as amulets (Figure 7), heart scarabs, funerary figurines, coffins, sarcophagi, and even on tomb walls. Spells can also be found written on leather rolls, linen shrouds, and individual linen mummy bandages.

An innovation of the Book of the Dead is the appearance of vignettes or images that appear together with the written words of the spell. Pyramid Text spells did not contain any associated images and use of imagery with Coffin Text spells is rare. The vignettes in the Book of the Dead were important components of these spells; the illustrations often related in some way to the spell’s contents or the way in which the spell should be carried out.

Chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead

Certain Book of the Dead spells seem to have been more commonly used than others, and many more examples of these popular spells are preserved. Chapter 125 is one of the best-known. This spell contains several components, including the so-called Negative Confession and a vignette depicting the weighing of the heart of the deceased during the final judgement (Figure 8). This spell describes how the deceased enters a hall called “the Broad Court of the Two Goddesses of What is Right.” In this divine court room, the deceased must declare their innocence before Osiris and a divine tribunal of 42 gods. They also must greet these deities and assert that they know the names of all the gods present (Figure 9). After greeting the divine judges, the deceased makes assertions that emphasize how they have acted in accordance with the ideals of maat, the Egyptian concept of truth and justice:

“See I am come before you, there being no evil of mine, no crime of mine, no wrong of mine, no witness to me, none against whom I have done anything. I live on what is right, I consume what is Right, I have done what men ask and what pleases the gods. I have pacified the god with what he loves. I have given bread to the hungry, beer to the thirsty, clothes to naked, a ferry to the boatless. I have offered divine offerings to the gods, and voice offerings to the blessed dead” (Translation by S. Quirke, Going out in daylight - prt m hrw: the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: translation, sources, meaning, p. 273).

Figure 8: The weighing of the heart as seen in the Book of the Dead of Hunefer (EA9901,3). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 9: Part of the Book of the Dead papyrus of a woman named Anhay showing the so-called “Negative confession” (EA10472,6). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Then the deceased would recite the so-called Negative Confession wherein they claim to be pure of heart and state that they have not performed various types of wrongdoings. These misdeeds include actions that would have harmed the living or offended the gods in some way. The deceased makes statements such as, “I have not caused ailment; I have not caused hunger; I have not caused tears; I have not killed,” and “I have not reduced the offerings in the temples; I have not harmed the offering-loaves of the gods” (Translation by S. Quirke, Going out in daylight - prt m hrw: the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: translation, sources, meaning, p. 271).

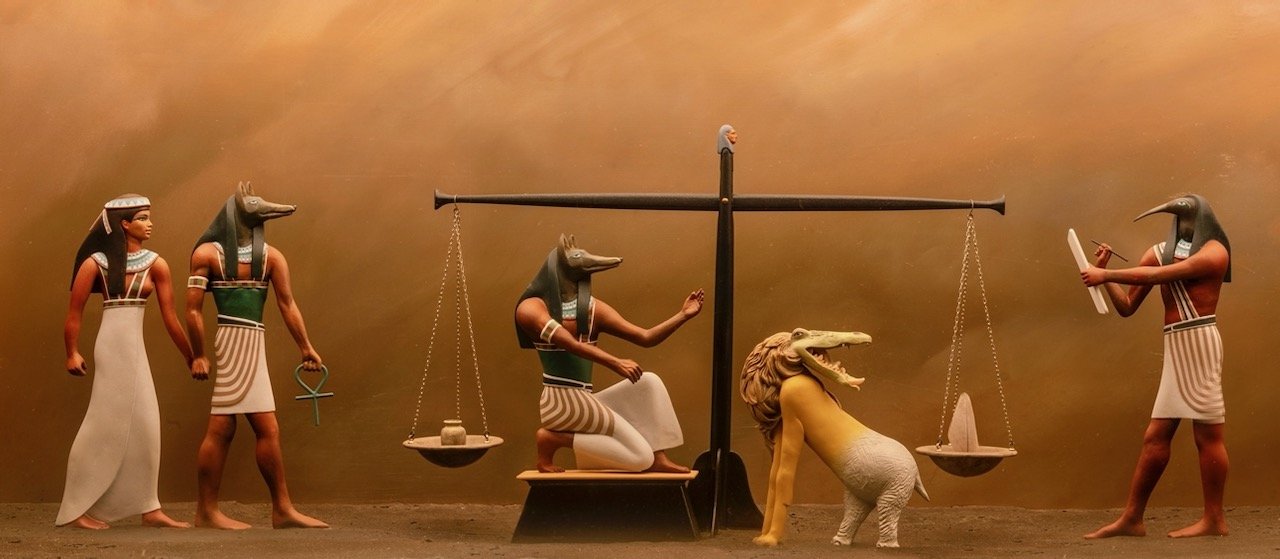

After making this testimony, the deceased would be judged by the divine tribunal. The way this judgment would be done is dramatically depicted in the Book of the Dead vignettes that accompany the Chapter 125 spell. A colorful diorama in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian gallery illustrates this final judgment and weighing of the heart. This display is based on vignettes from a Book of the Dead papyrus belonging to a woman named Isty, which is housed in the Field Museum in Chicago (Figure 10). Here we see the jackal-headed god Anubis leading the deceased to a large doubled-panned balance scale, while Osiris watches from his throne. One pan of the scale holds the heart of the deceased, while the other holds a feather representing maat (order, balance, truth). The Egyptians believed that the heart contained a record of all the good and bad that one did during their lifetime. Since bad deeds made the heart heavy, the ideal result of this test would be that the heart of the deceased would be free of bad deeds and would be equal in weight to the feather. In that case, the deceased would be judged worthy of the afterlife. If the heart were judged to be heavy, it would be fed to the devouring demon called Ammit whose fearsome form consisted of a crocodile head, the front paws of a lion, and the lower body of a hippopotamus. If Ammit gobbled up the heart, the deceased would die a second, permanent death and would not be granted an afterlife.

Figure 10: View of a miniature diorama in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian gallery illustrating the weighing of the heart.

Book of the Dead spells inscribed on funerary objects

Another popular Book of the Dead spell related to the final judgement and the weighing of the heart is found on a particular type of amulet known as a heart scarab (Figure 11). Small amulets in the form of scarab beetles were commonly used by the living as seals (much like a modern signet ring). Heart scarabs, in contrast, were larger in scale and were reserved for funerary purposes. They were typically placed upon the chest of the mummified body of the deceased. These scarabs were usually carved of greenish stone, and their flat bases were inscribed with a the Book of the Dead spell that contains a text asking the heart to speak well on the deceased’s behalf during the weighing of the heart. In Chapter 30A, the deceased appeals to their own heart saying, “Do not stand against me as witness, in the presence of the lords of offerings. Do not say against me ‘he did do it, truly.’ Do not create things against me in the presence of the great god, lord of the west.” Finally, the spell ends with the wish, “He is buried on the west side, enduring upon earth, not dying in the west, transfigured in it” (Translation by S. Quirke, Going out in daylight - prt m hrw: the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: translation, sources, meaning, p. 98).

Figure 11: An example of a heart scarab. The rounded upper side of the amulet is carved to look like a beetle while the flat side of the amulet is inscribed in hieroglyphs containing a Book of the Dead spell. Image courtesy of the Penn Museum (E6755).

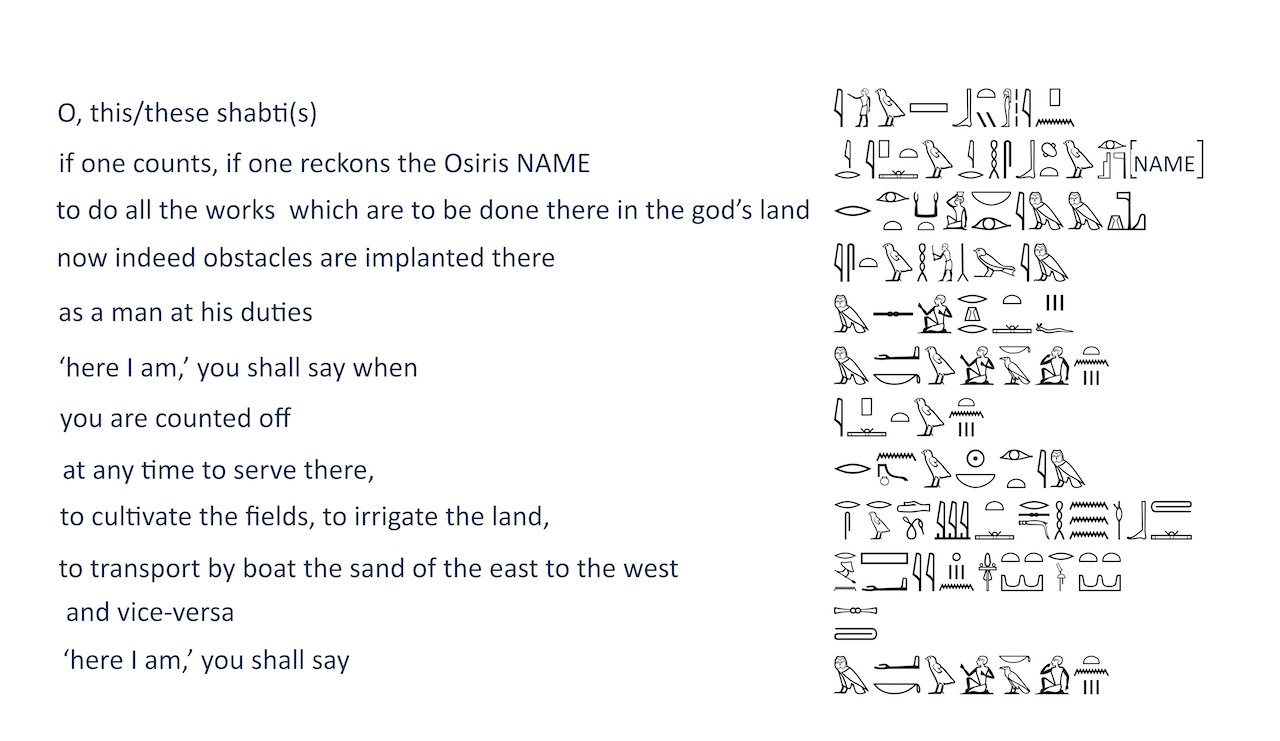

Funerary figurines known as shabtis (or ushabtis) were a common part of many ancient Egyptian funerary assemblages. These small figurines in the form of a mummified individual could be made from a variety of materials. Many shabtis are inscribed with Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead, also known as the “Shabti spell.” Their function was to magically carry out manual labor for the deceased in the afterlife. Sometimes this spell appears in papyrus copies of the Book of the Dead. The Glencairn collection includes several examples of shabtis inscribed with this spell (Figures 12–14).

Figure 12: Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead can appear on papyrus as seen here on the left. This is part of the Book of the Dead of Nebseny (EA9900,10). © The Trustees of the British Museum. The vignette above the text depicts a funerary figurine in the form of a mummified individual. This spell is often found on funerary figurines like this faience shabti for a man named Psamtek, seen here on the right (Glencairn Museum E69).

Figure 13: A translation of Chapter 6 of the Book of the Dead and the hieroglyphic text of the spell (translation from G. Janes, 2002, p. xix).

Figure 14: An abbreviated version of the shabti spell can be seen on the brilliant blue faience shabti belonging to a woman named Asetemkhebit, the wife of the High Priest of Amun Pinudjem II (Glencairn Museum E120).

Book of the Dead spells written on mummy bandages

Innovations appeared throughout Egypt’s long history of funerary practices. Just as the methods of mummification changed over time, so did the associated materials, rituals, and preparations that accompanied the burial of the deceased. Linen was one essential component for the mummification process. Evidence for linen production in Egypt appears in the archaeological record as early as 5,000 BCE. Linen was used to wrap the corpse as early as the First Dynasty, and from that time forward, the use of these wrappings evolved over time to produce what we think of as a typically wrapped Egyptian mummy. Linen wrappings were also used in the production of animal mummies (Figure 15). By the fourth century BCE a new funerary tradition emerged that saw spells from the Book of the Dead being written directly on narrow linen bandages that were wrapped around the mummified body. In so doing, these magical funerary spells were placed directly on (and in fact, encircling) the body, further ensuring that the deceased would have access to this protection after death. Many examples of these inscribed linen bandages seem to have come from cemeteries in the northern part of Egypt, particularly in the areas of Memphis and Herakleopolis (Figure 16).

Figure 15: A crocodile mummy and its associated linen wrappings from the Egyptian collection at Glencairn Museum E95-96.

Figure 16: Left: A miniature diorama of a mummy being wrapped in linen bandages in the Egyptian gallery at Glencairn Museum. Right: Inscribed mummy wrappings were placed on the wrapped body of the deceased as this drawing illustrates (after Kockelmann 2008, fig. 23).

Many examples of inscribed linen bandages dating to the fourth through the second century BCE are in museum collections around the world, but for many years, this category of artifact was largely overlooked. Scholarly work in the late 1990s began to focus attention on this material and in 2008, Holger Kockelmann produced a major study of these inscribed bandages. Another important resource for the study of material of this type is work of the “Totenbuch-Projekt” (Universität Bonn). For over 20 years, this research group has compiled almost all extant sources of the Book of the Dead worldwide and the resulting database contains approximately 3,000 records of Book of the Dead spells dating from the late 17th Dynasty through the Roman Period. The database has been publicly accessible on the internet since March, 2012. They have catalogued spells written on papyrus, leather, coffins, as well as on linen mummy wrappings and other media. With regard to Book of the Dead spells written on linen mummy wrappings, the Totenbuch-Projekt’s database lists a total of 1,400 examples belonging to the bandage sets from 775 individual owners.

Inscribed mummy bandage in the Glencairn Museum collection

Figure 17: The names of Padiwesir and his mother Tadiwesir are written in hieratic on the linen mummy wrappings. Here one can compare the cursive hieratic with their names written in hieroglyphic signs.

The inscribed mummy wrapping in the Glencairn collection was acquired in 1989 at auction at Sotheby’s. This linen fragment measures 6.3 cm in height and 33.6 cm in length. It is inscribed in black ink with a text in hieratic, the cursive form of the hieroglyphic script. Hieratic is read from right to left. The text indicates that this linen strip was owned by a man named Padiwesir, whose name means, “The one whom the god Osiris gave.” The text does not give us any information about the position or profession of the deceased, but his mother’s name also appears. Her name was Tadiwesir, the female version of her son’s name. The fragment can be dated to the Ptolemaic Period (305–30 BCE) (Figure 17).

The text on the bandage is written in horizontal lines with parts of four columns preserved. The first column on the right is incomplete. The second and third columns are complete, while the fourth column on the left is missing a few signs of each line where the linen is frayed. The spells on this fragment have been identified as Book of the Dead Chapters 72 and 74. Both spells were intended to enable the deceased to leave the dark confines of the tomb. Chapter 72 is entitled, “A spell for going out by day and opening the tomb chamber.” Most of this spell is missing from this linen fragment; only traces of the text remain in the first column on the right.

Chapter 74 is a spell of a similar nature and is titled, “A spell for hastening on foot and going out from the earth.” A translation of a version of this spell in a Book of the Dead papyrus of a man named Nu (British Museum EA 10477) reads:

“May you do your deed, Sokar! May you do your deeds, Sokar! He who is in the foot in the god’s land. I am the one who shines, [who is over the sector of] the sky. I go out to sky; I climb on the sunlight. O weary one! O weary one! I walk wearily on the riverbanks of their workers (?) in the god’s land” (Translation by S. Quirke,Going out in daylight - prt m hrw: the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: translation, sources, meaning, p. 176; see Figure 18).

Figure 18: Another example of vignettes 66 and 68 can be seen on the Book of the Dead of Iufankh as it appears in Lepsius’s 1842 publication of this papyrus, Das Todtenbuch der Ägypter, nach dem hieroglyphischen Papyrus in Turin, pl. xxv.

Just as the individual Book of the Dead spells have modern numbers, so too do the vignettes. The vignettes seen here are identified as numbers 66 and 68. These scenes are drawn in black ink and appear above the second column of text. On the right is an image of the deceased. He stands facing right and holds a staff in his proper left hand. Behind him is an offering stand with loaves of bread and a lotus blossom piled atop. To the left of the table with offering is an image of a goddess in a shrine (see lead image, top).

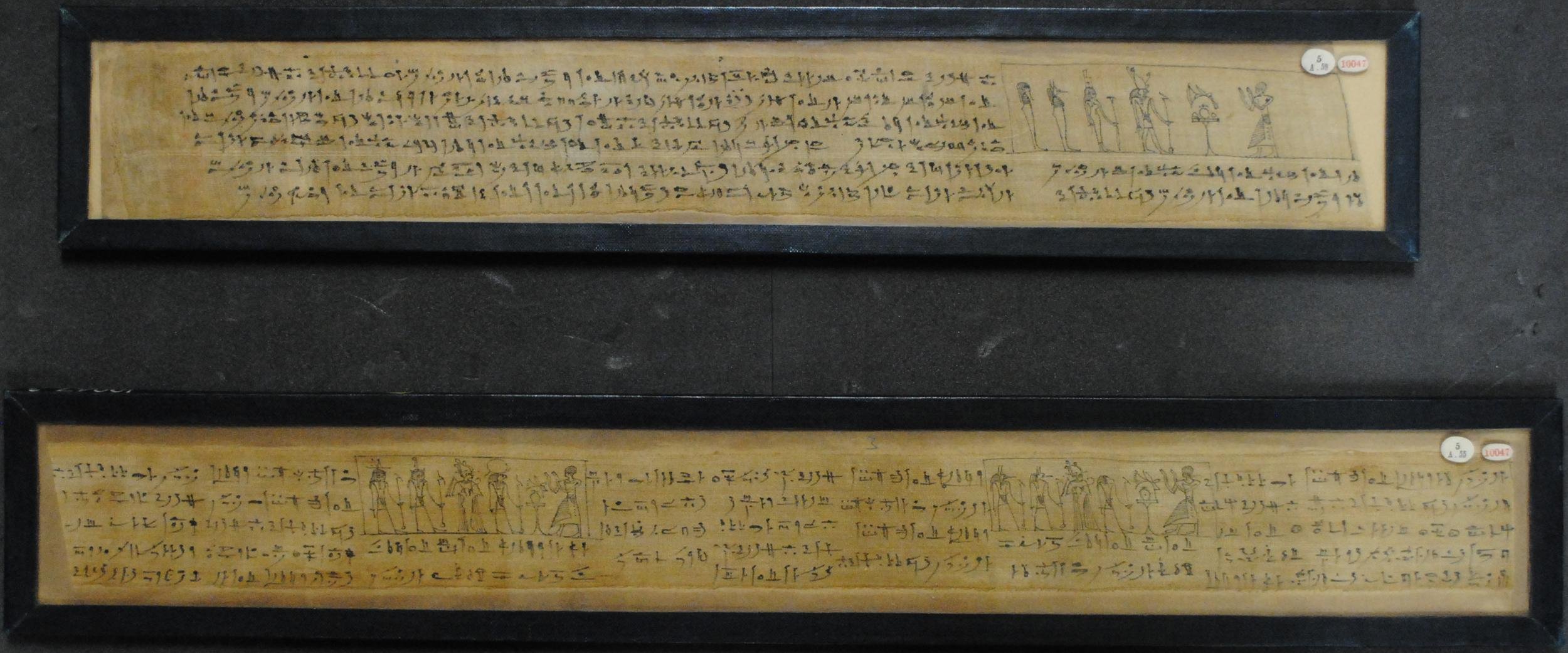

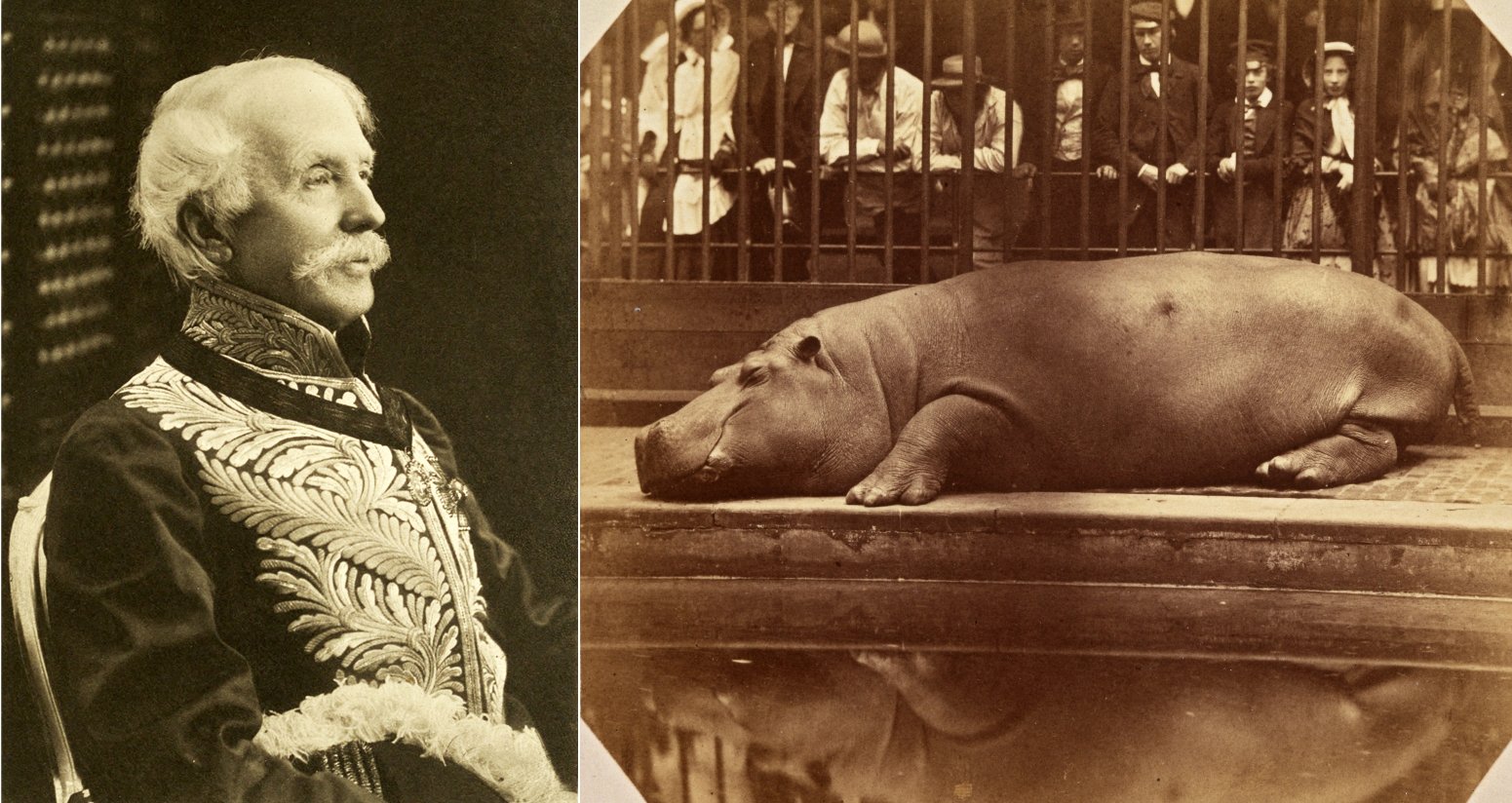

As noted above, many of these sets of mummy bandages were divided up by antiquities dealers in the late 1800s. This seems to have been the case with Padiwesir’s wrappings, as pieces of his linen bandages are housed in several institutions around the world. The Totenbuchprojekt Bonn, TM 114053, notes that sections can be found in the British Museum (BM EA 10047, 5–7) (see Figure 19); The J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles (83.AI.47.1.1 through 83.AI.47.1.6); the Biblioteca Archeologica e Numismatica in Milan (E. 0.9.40453); and the Newark Museum of Art (88.261). In addition, a fragment of Padiwesir’s inscribed wrappings is housed in a private collection in Belgium. The Totenbuchprojekt website also lists several sections of Padiwesir’s wrappings as being “Standort unbekannt” (unknown location). From the photograph shown on the website, it is clear that the Glencairn Museum fragment is the one listed as “M. Standort unbekannt [6].” This fragment is identified as coming originally from the collection of Charles Augustus Murray (1806–1895), a British diplomat who served as consul-general in Egypt during the years 1846-1853. A curious sidenote to his consular career was that Murray arranged for the transportation of the first hippopotamus seen in England. The impressive beast was named “Obaysch,” and he was brought to the London Zoo in 1850 where he became a sensation. This venture earned the consul-general the nickname, “Hippopotamus Murray,” and he frequently came to the zoo to visit with the creature (Figure 20).

Figure 19: Sections of Padiwesir’s mummy wrappings are housed in the British Museum (EA10047,7). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Figure 20: A photograph of Sir Charles Augustus Murray (1806–1895) and Obaysch the hippo resting in the London Zoo in a photograph taken in 1852.

Some sets of inscribed mummy wrappings belonging to a single individual could be impressively long. For example, Holger Kockelmann studied the set belonging to a man named Hor and estimated that his inscribed bindings totaled about 180 feet (54–55m) long. However, many examples in museums today are much shorter since they were often cut into pieces after their discovery and sold individually by antiquities dealers in Egypt. This seems to have been the case with the fragment in Glencairn Museum. Taking into account the measurements of the identified pieces of Padiwesir’s linen bandages, the length of his inscribed wrappings totals approximately 42 feet (1305 cm) in length. Continuing research in collections around the world may see this measurement increase. In 2021 researchers identified a previously unknown section of Padiwesir’s wrappings housed at the University of Canterbury's Teece Museum in New Zealand. This fragment was purchased at auction on behalf of the university in 1972 at Sotheby’s, but it formerly belonged to the collection of Charles Augustus Murray, the original owner of the Glencairn linen fragment.

While it is unfortunate that Padiwesir’s wrappings have been so widely dispersed, with projects like the work of the Totenbuchprojekt database, research by Egyptologists like Holger Kockelmann, and the increased availability of museum collections online, we can come closer to reconstructing Padiwesir’s complete inscribed linen set virtually. Padiwesir has truly “come forth by day” and has traveled the world during his afterlife!

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Associate Curator, Egyptian Section, Penn Museum

University of Pennsylvania

Further Reading

Allen, Thomas George 1974. The Book of the Dead or Going Forth by Day: ideas of the ancient Egyptians concerning the hereafter as expressed in their own terms. Edited by Elizabeth Blaisdell Hauser. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 37. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/saoc37.pdf

Caluwe, Albert de 1991. Un Livre des Morts sur bandelette de momie (Bruxelles, Musées royaux d'Art et d'Histoire E. 6179). Bibliotheca Aegyptiaca 18. Brüssel: Ed. de la Fondation Egyptologique Reine Elisabeth. Janes, Glenn 2002. Shabtis: a private view. Ancient Egyptian funerary statuettes in European private collections. Photographs by Tom Bangbala. Paris: Cybèle.

Kockelmann, Holger 2008. Untersuchungen zu den späten Totenbuch-Handschriften auf Mumienbinden, 3 vols. Studien zum Altägyptischen Totenbuch 12. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Lepsius, Richard 1842. Das Todtenbuch Der Ägypter Nach Dem Hieroglyphischen Papyrus In Turin.. Leipzig: G. Wigand.

Naville, Edouard 1886. Das aegyptische todtenbuch der XVIII. bis XX. dynastie. Berlin: A. Asher & co.

Quirke, Stephen 1996. Book Review: Un Livre des Morts sur Bandelette de Momie (Bruxelles, Musées Royaux D’Art et D’Histoire E.6179). The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 82(1), 230–232.

Quirke, Stephen 2013. Going out in daylight - prt m hrw: the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead: translation, sources, meaning. GHP Egyptology 20. London: Golden House.

Quirke, Stephen 2013. Review: Kockelmann, Holger 2008. Untersuchungen zu den späten Totenbuch-Handschriften auf Mumienbinden, 3 vols. Studien zum Altägyptischen Totenbuch 12. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. Journal of Near Eastern Studies 72 (2), 319-322.

Scalf, Foy (ed.) 2017. Book of the Dead: becoming God in Ancient Egypt. With new object photography by Kevin Bryce Lowry. Oriental Institute Museum Publications 39. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/oimp39.pdf

Silverman, David P. 2015. “The wadj amulet of feldspar and its implicit and explicit wish.” In Nyord, Rune and Kim Ryholt (eds), Lotus and laurel: studies on Egyptian language and religion in honour of Paul John Frandsen, 373-389. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

Silverman, David P. 2016. “The origin of the Book of the Dead spell 159.” In Collombert, Philippe, Dominique Lefèvre, Stéphane Polis, and Jean Winand (eds), Aere perennius: mélanges égyptologiques en l'honneur de Pascal Vernus, 741-762. Leuven: Peeters.

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox (12 times per year)? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.