Glencairn Museum News | Number 4, 2023

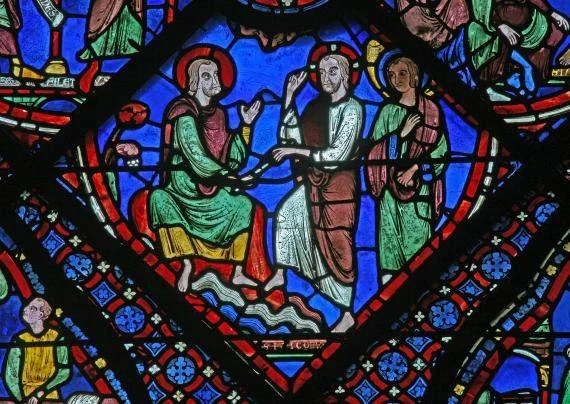

This 13th-century panel of stained glass, which depicts Christ entrusting Mary's soul to the archangels Michael and Gabriel after her death (03.SG.241), is installed in a lunette window in the apse of Glencairn’s Upper Hall.

In the early twentieth century, Raymond Pitcairn amassed a collection of medieval sculpture and glass to inform the stone masons and glass artists building the Swedenborgian Cathedral in Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania. His nearby home, Glencairn, also built in a medieval style, is the repository of his collection and open today as a museum. He purchased the early thirteenth-century panel discussed here (03.SG.241) in London in the 1920s. Set into a lunette of twentieth-century glass made in Bryn Athyn, it graces the apse of the Glencairn living room. The panel illustrates the moment after Mary’s death when Christ entrusts her soul for safekeeping to the archangels Michael and Gabriel (Figure 1).1 According to apocryphal gospels that describe Mary’s death and assumption to heaven, the angels care for Mary’s soul until it is reunited with her body in heaven after the Resurrection. The rondel’s style has been convincingly linked to glass painters active in the second quarter of the thirteenth century at the cathedral of Saint-Julien in Le Mans, an atelier that was previously associated by Louis Grodecki to glass of the Charlemagne window at Chartres Cathedral. Subsequent related work is found at the cathedral at Tours to the south, and a small priory church at Vivoin just to the north of Le Mans.2 This text continues this investigation to consider possible alternatives for the origins of the painters’ style.

Figure 1: Christ Receiving the Soul of His Mother, pot-metal glass and vitreous paint, c. 1230–1240 rondel set into a lunette of 20th-century glass made in the Bryn Athyn glassworks, Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA, 03.SG.241.

Of eastern Mediterranean origin, the story of Mary’s death was introduced to western Europe and the Latin church in the sixth century and quickly became a popular theme in Latin liturgy and western European art. The visual sources came from eastern Greek images of the feast of Mary’s death, called the Koimesis, where Christ stands behind Mary’s deathbed surrounded by the Apostles and passes her soul up for safekeeping to the descending angels. Most western examples follow this pattern as well, except for a number that were made around the turn of the thirteenth century, when new elements enter representations of the scene. The Glencairn panel exemplifies this departure. For example, the rondel shows the scene of Christ holding Mary’s soul isolated from that of her death, and instead of showing Mary’s child-sized soul as clothed, it is depicted as naked.

Unlike their predecessors, who either dismissed Mary’s death as apocryphal or debated its precise nature, thirteenth-century theologians, including Vincent of Beauvais (c. 1184–c. 1264), accepted the legend as historical, and focused on its spiritual and doctrinal meaning. As a Dominican friar at the Cistercian monastery of Royaumont, which enjoyed the patronage of the French royal house, Vincent understood the assumption of Mary’s soul and body into heaven as proof not only of her grace above all others, but also as a reiteration of God’s promise of general salvation and resurrection. In her volume on the iconography of the Virgin, Gertrud Schiller argues that the depiction of Mary’s soul as naked illustrates this theological shift.3 According to Schiller, the association of Mary with the naked souls of the dead rising from their tombs in images of the Last Judgment would have reminded medieval viewers of the urgency of ensuring their own resurrection.4

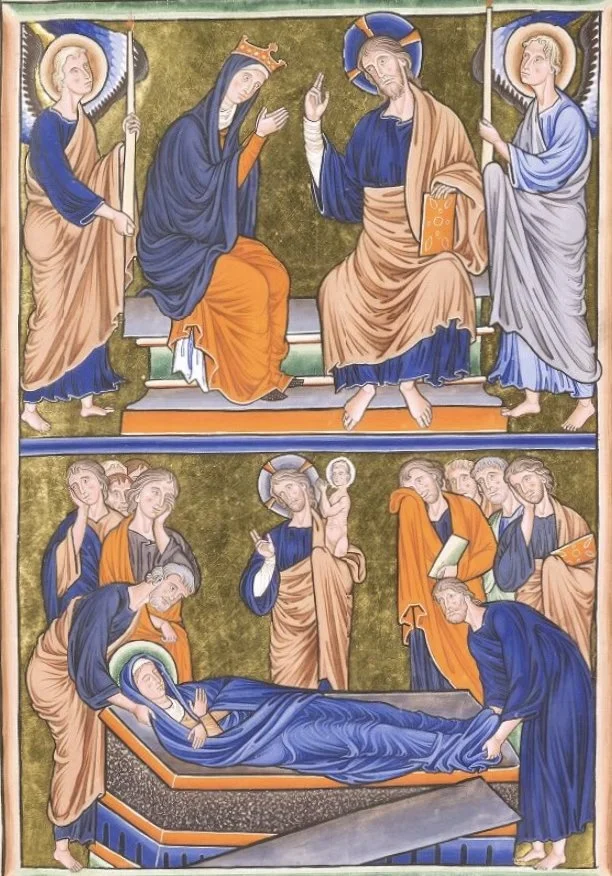

One of the earliest surviving examples of the naked soul of Mary is found in the Ingeborg Psalter, which was produced for the French queen Ingeborg between 1193 and 1195 (Figure 2).5 On the bottom half of the folio devoted to the Entombment and Coronation of the Virgin, Christ holds his mother’s naked soul as the apostles lower her body into the tomb. Her lifeless body reminds the viewer that she has suffered a human death, which she must if Christ is human as well as divine, but her naked soul in Christ’s arms celebrates her special status among humans and her posthumous reunion with her son. By extension, if believers can be as perfect as the Virgin in the eyes of God, they will enjoy a similar afterlife. The Coronation of the Virgin in the upper half of the folio restates this promise with a different emphasis. The reunification of the Virgin and the resurrected Christ is enabled in part by their conflation as the Bride and Bridegroom in the Song of Songs, which was understood as a typological allegory for the spiritual union of every Christian with Christ. The depiction of the Virgin as a rising naked soul in the psalter and the Glencairn panel illustrates this concept and invests the story of Mary’s death with additional meaning.6

Figure 2: Dormition and Coronation of the Virgin, Ingeborg Psalter, Chantilly, Musée Condé, ms. 009, 34r. Creative Commons.

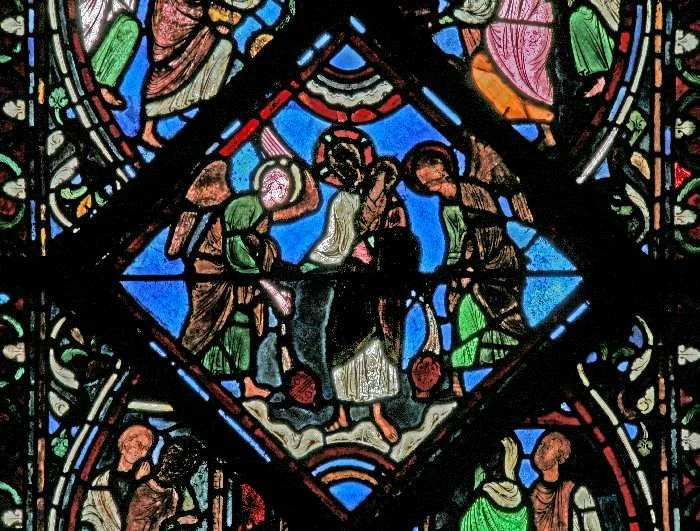

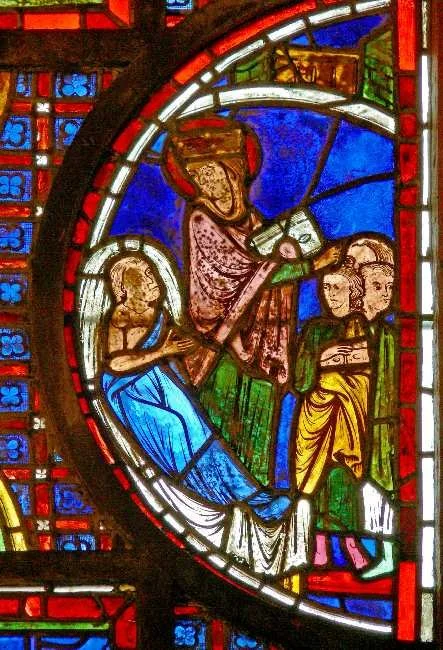

While the combination of Christ holding his mother’s soul with the Dormition and Coronation appears in contemporary manuscripts and sculpture,7 it is only in the medium of stained glass that the scene occurs completely separated from the larger events. The phenomenon is explained by the expansion of the Gothic window opening, which required the stained-glass artists to stretch the narrative into more scenes. In the Glorification of the Virgin window in the nave of Chartres Cathedral, a smaller quatrefoil with Christ holding the nimbed and naked soul of Mary sits directly above the larger Dormition panel. Like their counterparts in the Glencairn panel, the angels at Chartres step forward and extend their hands expectantly to receive Mary’s soul, but instead of gesturing to the scene below as in the Glencairn panel, Christ raises his hand in blessing (Figure 3). As Jane Hayward observed, the same division of events is also found in the Virgin window, dated 1220–25, in the Lady Chapel of the church of Saint-Quentin (Aisne) (Figure 4).8 Unlike the earlier window at Chartres, at Saint-Quentin the two scenes are given equal space. The diamond-shaped panel of Christ holding the soul of the Virgin is placed directly above the Dormition panel of the same size. At Saint-Quentin, Christ’s gesture of blessing is directed down toward the body of Mary in the Dormition panel immediately below. The identical gesture in the Glencairn Christ suggests that it would also have been placed directly above a panel illustrating the Dormition.

Figure 3: Christ with the Soul of His Mother, panel from the Glorification of the Virgin window, Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Chartres.

Figure 4: Christ with the Soul of His Mother, panel from the Glorification of the Virgin Window (window 2), Church of Saint-Quentin (Ainse).

The surviving examples indicate, therefore, that the iconographic antecedents of the Glencairn panel come from a group of early thirteenth-century images that enlarged the traditional idea of the humanization of the Virgin through her Dormition and Assumption to suggest the idea of universal resurrection for all faithful. The earliest exemplars are found in illuminated manuscripts produced for the French royal court. There are examples in sculpture as well, but the most direct comparisons are found in stained glass, where the expansion of high Gothic windows may have prompted designers to stretch the narrative into a greater number of individual scenes.

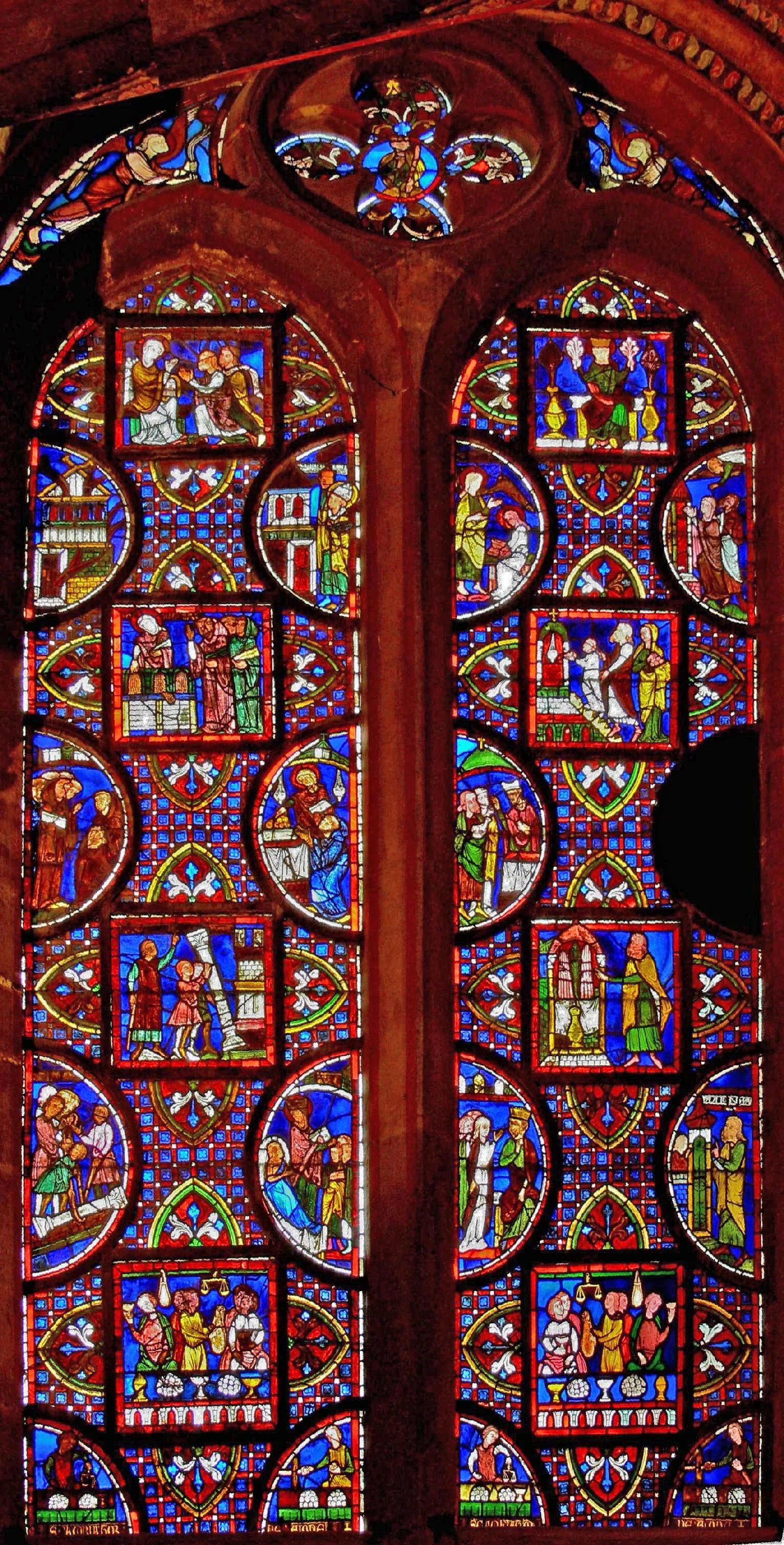

Hayward clearly demonstrates in her entry on the panel for the exhibition catalogue Radiance and Reflection that the style of the Glencairn panel is virtually identical to the thirteenth-century glass presently in the Lady Chapel of the cathedral of Saint Julien at Le Mans.9 Badly damaged in the sixteenth century when the town was occupied by the Huguenots, the chapel lost ten of its seventeen medieval windows. Of the seven surviving windows, the two best preserved are placed side by side in a double lancet donated to the cathedral by the money changers of the city of Alonnes (Sarthe). It is in these windows at Le Mans, which depict the Infancy and Miracles of the Virgin, that one finds the closest parallels to the Glencairn panel: open compositions, classicizing but linear drapery, and faces with wide, staring eyes and heavy, square chins (Figures 5 and 6).10

Figure 5: The Changers of Alonnes window (Childhood and Miracles of the Virgin), Window 5, Lady Chapel, Cathedral of Saint-Julien, Le Mans.

The emphasis given to Marian themes in the Le Mans axial chapel glazing program has been considered remarkable by scholars despite its thirteenth-century date, by which time the cult of the Virgin had become regularly expressed in plastic, manuscript, and glass art in France.11 Within such a program one would expect to have found a window devoted to the Death and Coronation of the Virgin. A nineteenth-century window of the subject presently fills the lancet of the easternmost straight bay of the south side of the chapel.12 According to Eugène Hucher, whose books of tracings record the nineteenth-century, pre-restoration state of the glass, this bay was filled with fourteenth-century grisaille, “dun effect mediocre.”13 Nowhere in Hucher’s publications is there record of fragments that could have been part of a Dormition/Coronation window. And the provenance of the Glencairn panel cannot be traced back further than about 1920, by which time it was in Raymond Pitcairn‘s collection.14 Thus, only style is left to link the Glencairn panel to the Le Mans Lady Chapel. However, given the strength of the stylistic affinities recognized by Hayward, we can be sure that the isolated Glencairn panel and the Changers window in situ at Le Mans are by the same artists. Moreover, it is quite likely that the Glencairn Christ Receiving His Mother’s Soul is a survival from one of the Lady Chapel windows destroyed by the Huguenots in 1562, which would have included a window devoted to the Virgin’s death, assumption, and coronation.

The composition of the Glencairn rondel is simple and direct. The designer has reduced the number of participants to the minimum needed to tell the story and eliminated extraneous background elements. Instead, the handsomely proportioned figures move calmly against a solid blue background. The curved border of the panel functions as both groundline and frame for the figures, who extend neither hand nor foot beyond its confines. The erect stance of the figures defines the drapery, which is painted with firm lines. The fabric hangs in vertical box pleats and quiet scoop folds. The sleeves of the angels fall in deep swags turned back at the wrists. As the angels stride forward, their skirts pull across their forward legs in curves. Dimpled and hooked folds suggest the pull of the material against their wrists and shins. Little attempt has been made to distinguish the different weights of fabric except in the modeling of Christ’s tunic. Here the artist has used quick lines that end in upturned arrows to imply a material lighter than the outer mantle. This passage best illustrates the dependence of the artist on the Muldenfaltenstil, or Year 1200 Style, which dominated the glazing programs of such important buildings as Laon and Soissons around the turn of the thirteenth century. Working approximately two decades later, the artist of the Glencairn panel has reduced the classicizing damp folds of the Muldenfaltenstil to a precise and formal linear system.

Figure 6: Panel of the Virgin raising a child, from the Changers of Alonnes window (Childhood and Miracles of the Virgin), Cathedral of Saint-Julien, Le Mans.

The faces of the Glencairn figures are rendered in three-quarter view and modeled with a layer of matte paint. They are characterized by a heavy, sweeping jaw and large, staring eyes. The lines of the eyes are open at the outer corners, and a second set of lines describes the lid. Thick pools of trace paint form the pupils. A heavy line shapes the far eyebrow and is lengthened downward to delineate a long and slightly curved nose. The inner corner of the near eyebrow extends to create the interior contour of the nose. The upper lip of the mouth is formed by a decisive undulating line. Below, the half-moon lower lip rides on top of a circle that articulates the chin. Parted at the center, hair arches over a broad forehead and falls to reveal only the lobe of an ear.

The colors of the Glencairn panel also correspond directly to the palette of the Le Mans glass, which is dominated by yellow, green, murrey, and white. In the Glencairn panel Christ wears a green robe and white mantle. His cruciform halo is red and white. The angel to Christ’s left wears a green robe and a yellow mantle and has white wings. The wings of his companion are yellow, his robe is murrey, and his mantle is white. This careful reversal of the color scheme of the angels’ wings and robes is a hallmark of the Le Mans artists and can be seen throughout the Lady Chapel glass. The stained-glass borders of the individual panels are simple fillets of red or blue with white pearls. Vegetal ornament emerges only in the borders of the windows and as the bosses that link the scenes to one another.

The circular format of the medieval portion of the Glencairn panel corresponds in shape and size to panels in the Le Mans Lady Chapel, which are composed of centralized square, circular, and quatrefoil medallions with flanking semi-circular and half-quatrefoil panels, all of which are held in the windows by curved iron bars. The use of forged iron bars that conform to the shapes of the window composition is found primarily in earlier stained glass, as the method requires more labor and expense than the simple rectangular irons that are favored in later and larger windows.

The date of the Glencairn panel and companion glass in the Lady Chapel is coeval with the first building campaign at Le Mans. In 1217, the cathedral chapter received permission from the French King, Philip Augustus (r. 1180–1223), to dismantle the Gallo-Roman wall to make way for their new High Gothic cathedral eastern extension. In 1221, the chapter purchased land to the east of the Gallo-Roman wall, and construction could begin. Scholars assume the lower levels, including the Lady Chapel, were substantially complete by 1231, when King Louis IX (r. 1226–1270) ordered the chapter to fill the gaps in the city wall around the new building. Thus, the fabric of the building was ready to receive glass by the early 1230s. The new choir high altar was dedicated in 1254, which provides a terminus for the entire eastern end of the cathedral.15

Glass stylistically related to the Lady Chapel of Le Mans and the Glencairn panel exists in the cathedral of Tours (Indre-et-Loire), the choir of which was dedicated in 1267. Presently inserted in three windows of a lateral choir chapel, the stained glass includes scenes devoted to the lives of Saint John the Evangelist, Saint James the Greater, and miscellaneous saints. The fragments are the remains of the earliest glazing program of the choir, which was begun perhaps as early as the late 1230s and certainly by the 1240s.16 The most striking similarity for the glass at Le Mans is the spandrel-shaped panel of a censing angel, which is very close to the censing angels that surround the rosette above the Changers window at Les Mans (Figures 7 and 8). The compositional schemes are the same, and they feature common elements––fillet borders, upswept wings, solemn and impassive faces, and simplified classicizing drapery styles. The second site with glass related to the Le Mans Lady Chapel is the priory church of Vivoin, north of Le Mans (Sarthe), dated to the 1250s. The three lancets in the flat east end contain glass made sometime in the middle of the thirteenth century that display forms similar in style to the Theophilus window at Le Mans.17

Figure 7: Censing Angel from the Changers of Alonnes window (Childhood and Miracles of the Virgin), Window 5, Lady Chapel, Cathedral of Saint-Julien, Le Mans.

Figure 8: Censing Angel, The Lives of St. Peter (and Paul?) window, Cathedral of Tours.

Given the dates of these three monuments, it appears that the linear and classicizing style of the Glencairn panel first appears in the west of France at Le Mans in the early 1230s. The style recurs at Tours in the 1240s, where it retains its earlier classicism and grace, but becomes more schematic and flattened. Finally, in the 1250s at Vivoin, only vestiges of the confident classicism of the first and most coherent phase of the style remain. The Glencairn panel illustrates the first phase of this style as it appears at Le Mans.

Louis Grodecki identified the artist of the Le Mans Changers window as the primary hand of the Le Mans ambulatory. According to Grodecki and the scholars who have followed him, the Le Mans ambulatory master derived his style from the Charlemagne atelier of Chartres Cathedral.18 Large and diverse, the Charlemagne atelier was responsible for finishing twenty-five windows in the Chartres choir by 1220. Grodecki compares the Le Mans glass to the Charlemagne window, which was produced by the master of the atelier, and to the Saint James window, produced by a different though closely related artist.19 Grodecki’s thesis is based on general similarities in the compositions, color schemes, and painting styles of the two monuments. A close examination of the comparison he offers indeed reveals similarities. For example, both the Chartres and Le Mans windows are composed of medallions set into a mosaic background by means of curved irons. However, this is a common system of window design for the time, and the Chartraine compositions are far more complex than those at Le Mans. The Charlemagne atelier and the Le Mans artist both rely on strong palettes of red, blue, green, and murrey, but the Chartres colors are closer to primary hues while the Le Mans colors are more acerbic and tertiary versions of yellow and green in combination with dazzling white. The drapery styles are clearly related as one can see from the turned back cuff of Christ’s tunic and the pull of his mantle across his leg in the Saint James window from Chartres, both of which occur in the Glencairn panel from Le Mans.

However, the differences in proportions and details of faces of the Chartres window and the Glencairn panel are marked, and while one can see both monuments participating in a general stylistic moment, the hands of the artists are quite different. In the Saint James and Charlemagne windows at Chartres, the drapery undulates over tall, thin figures, enhancing their movements and conveying their inner vitality (Figure 9). This contrasts with the formal linear patterns that define the reserved and staid Le Mans figures, as found in the Glencairn panel. Differences between the faces and hair are also striking, particularly between the Saint James and Le Mans figures, where Grodecki saw a strong resemblance.20 The Saint James figures have large ovoid heads, long, thin, and curved noses, and thin chins. Unlike the square hairline common to the Le Mans heads, the hairline of the Saint James figures begins in a mannered loop that descends into the forehead and arches back to reveal the brow. The Saint James faces are sorrowful, whereas the Le Mans faces carry a serene if opaque expression.

Figure 9: Panel from the St. James the Great window, Cathedral of Notre-Dame, Chartres.

While Grodecki admitted he had not found the exact hand of the Le Mans ambulatory master at Chartres, he nevertheless felt that the general similarities were strong enough to suggest a direct stylistic relationship between the two monuments.21 By connecting Le Mans with Chartres, Grodecki placed them within a chronology that uses the surviving monuments to describe a linear development in stained glass during the first half of the thirteenth century. In this chronology, one observes the reduction of the classicizing naturalism of the Muldenfaltenstil to a more linear and academic formula. However, as argued above, the common use of strong colors, open compositions, and medallion formats at the two monuments does not prove a direct relationship between the artists. Certainly, both the Chartres and Le Mans artists participated in various phases of the codification of the Muldenfaltenstil, but this suggests less that one monument is dependent on the other than that the two artists and their workshops were responding to similar trends in taste. More instructive are the fundamental differences between the softly modeled naturalism and animation of the Chartres figures and the crisp, deliberate drawing and spare compositions of the Le Mans Lady Chapel. These differences suggest not a linear relationship, but separate parallel sources for the two monuments.

Until the middle of the twentieth century, scholars considered Chartres to have been a major center of early thirteenth-century glass production. In 1946, while outlining the relation of French to English glass, Jean Lafond critiqued this theory with several general yet astute observations.22 He pointed to the unlikelihood that Chartres––a small town isolated in a rural area––was ever the center of a continuous glazing tradition. He argued that it was far more plausible that the masters of the Chartres windows were drawn from the talent available in the French capital. Lafond calculated that in addition to the cathedral, court, university, and conventual buildings, Parisian glass painters glazed sixty parish churches in the diocese of Paris during the late twelfth and thirteenth centuries. Paris was a thriving capital where “the glass painters’ ovens need never be put out.”23 Lafond concluded that Chartres should be considered not as a major center of glass production but as a monument which fortunately preserves the work of some of the masters of the Parisian glass industry. Following Lafond’s article, Robert Branner demonstrated the precedence of Paris in the realms of architectural design and manuscript production during the first third of the thirteenth century.24 That the capital would also have been a center for stained glass is logical. However, little Parisian glass from this period has survived, and despite efforts since the late twentieth century to draw attention to lesser-known survivals, Lafond’s theory is not easily tested.25 In addition, comparative studies, such as Virginia Chieffo Raguin’s work on Burgundian glass and Linda Papanicolaou’s work on Tours have begun to test Lafond’s contention that only the influence of Paris could explain why glass painting followed the same rapid evolution in all parts of France.26

Thirteenth-century stained-glass panels from the destroyed royal abbey church of Gercy (Essonne) now in the Cluny Museum in Paris are important survivals from the Parisian area. Among the fragments are three rondels dated to 1225, presently leaded into one window (Christ in Glory and two scenes from the life of Saint Martin), and two panels from a Tree of Jesse window.27 Raguin has shown that the artists of the Genesis cycle of the cathedral of Auxerre were ultimately stylistically dependent on the Gercy artist. She sees this as just one example of the influence of Parisian fashion on the glass painters of the province of Burgundy. A comparison of the style of the Saint Martin panels and the Glencairn Christ reveals a similar relation between the style of the capital and western France.

The style of Gercy depends on active line, relatively little modeling, and simple, open compositions. The windows are designed with medallions surrounded by simple fillet borders set against mosaic backgrounds. These are all elements one would expect to find in a predecessor to the Le Mans ambulatory artists. The middle rondel of the St. Martin window, the dream of the saint, provides a close parallel to the Glencairn panel (Figure 10). The twisting of the sleeves around the extended arms of the Gercy angel and the blessing arm of the Glencairn Christ illustrate a reliance on similar linear reinterpretations of the Muldenfaltenstil. The figures attending Mary from the Gercy Tree of Jesse window provides an even closer parallel (Figure 11). In the faces of the Gercy and Glencairn angels one observes an almost exact correspondence between the jaws, eyes, brows, mouths, and earlobes.

Figure 10: Detail from a Saint Martin window from the church of Gercy, Paris, Musée Cluny.

Figure 11: Tree of Jesse panels from the church of Gercy, Paris Musée Cluny.

While the Gercy and Le Mans styles are particularly close, we can’t be sure the glass was painted by the same hand. At Le Mans, the drapery is more strictly codified and the forms beneath more substantial than in the glass from Gercy. The facial features of the Gercy and Le Mans angels are constructed according to the same linear formula, but their expressions are different. The Gercy angels are pert and cheerful; the Glencairn angels are startled and somber. Gercy may be only an echo of the glass that inspired the Le Mans artist; nevertheless the comparison presents a strong alternative to the Chartraine source traditionally given for the Le Mans ambulatory master and his followers at Tours and in Maine.

To summarize, in iconography and style the Glencairn panel is related to early thirteenth-century monuments from the Île-de-France. The closest iconographic parallel comes from the church of Saint-Quentin, to the north of Paris, a city that entered the royal domain of the French king in the first years of the thirteenth century.28 Charles Little linked this window to fragments of a Dormition window from the cathedral of Troyes––a connection that becomes more significant when one remembers that Maurice, the bishop responsible for the first campaign at Le Mans, served at Troyes before he was elevated to the see of Le Mans in 1216.29 Maurice was the first cleric in a century who was neither a canon of the Le Mans cathedral nor a member of the local nobility. His appointment is one example of the early thirteenth-century shift in the political orientation of Maine from England to France. As the capital of the county, Le Mans was part of a complex power struggle among Henry II of England, his sons, the local nobility, and the French monarchy. Philip Augustus of France took control of the area after his defeat of King John in 1204. In a shrewd conciliatory gesture to Plantagenet sympathizers in Maine, Philip awarded the city to Queen Berengeria, the widow of King Richard the Lionheart. Denied her rights by her brother-in-law, King John, Berengeria became a vassal of the French King Philip and helped to establish his law throughout the region. Le Mans came to her by virtue of her dower from Richard and as a widow she ruled there as countess. She was a devout woman who marshalled resources to found the Cistercian abbey of L’Epau near Le Mans in 1229. She also took an active interest in the Cathedral of Le Mans; and it was partially through her influence that the chapter received permission to destroy the Roman wall and extend their new choir, the area that includes the prominent Lady Chapel where the Glencairn rondel was originally placed.30

It is difficult to establish the precise nature of either Queen Berengeria’s or Bishop Maurice’s contributions to the creation of the choir and its glazing program. However, Maurice’s appointment and Berengeria’s vassalage to kings Philip and his successor Louis IX, along with the appearance of Parisian styles of architecture and painting at Le Mans, reflect the ascendancy of the French capital in the tastes of western France in the third and fourth decades of the thirteenth century. Both the iconographic sources of the Glencairn panel, the Ingeborg Psalter and Saint Quentin glass, together with the tantalizing links of the Le Mans painters’ style to Parisian sources such as the glass from Gercy, bring the Glencairn panel and the glazing of the lower portions of the Saint-Julien at Le Mans more firmly into the sphere of Paris and the French royal domain.

Mary Prevo

Senior Lecturer Emerita

Hampden-Sydney College, Farmville, Virginia

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Michael Cothren for suggesting that I revisit this paper. My thanks also to Ed Gyllenhaal, Curator at Glencairn Museum, for his encouragement and hospitality, to Desiree Varga for interlibrary loan help, and to Lucy Flint for her sharp editorial eye. Finally, I offer this in memory of Jane Hayward, who always said our job as art historians was to develop what she called, “old eyes.”

Endnotes

1. Glencairn Museum 03.SG.241. Pot-metal glass and vitreous paint, 72 x 98.8 cm (28 3/8 x 38 7/8”). Diameter of medieval rondel 62.3 cm (23 ½”). All glass from the pearled fillet out is modern. The central medallion of medieval glass is in excellent condition with only minor repairs: the middle level of the left angel’s left wing and the tip of the right angel’s right wing are stop gaps, unaltered pieces of old glass not original to the panel.

2. Jane Hayward and Walter Cahn, Radiance and Reflection: Medieval Art from the Raymond Pitcairn Collection, exh. cat., New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1982, pp. 175–78, cat. no. 65. For the connection to Chartres see: Louis Grodecki, “Les Vitraux de la cathédrale du Mans,” Congrès archéologique de France, 119, 1961, pp. 59–99. For the connection of Le Mans and Tours see: Linda Morey Papanicolaou, “St. Martin and the Beggar: A Stained-Glass Workshop from the Lady Chapels of the Cathedrals of Le Mans and Tours,” Studies on Medieval Stained Glass: Selected Papers from the XIth International Colloquium of the Corpus Vitrearum, United States, Occasional Papers 1, ed. Madeline Caviness and Timothy Husband, New York, 1985, pp. 60–69.

3. Gertrud Schiller, Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst, Vol. 4.2, Maria, Gütterslohn, 1980, pp. 102–104.

4. For an overview of this iconography see: Schiller, Ikonographie der christlichen Kunst, vol. 4.2, Maria, 1980, pp. 84–92.

5. Chantilly, Bibliothèque du château, ms. 0009 (1695), 34r. Creative Commons, Virtual Library of Medieval Manuscripts (BVMM). For a monograph on the psalter, see Florens Deuchler, Der Ingeborgpsalter, Berlin, 1967.

6. Shiller, op. cit., pp. 90-92 and 102–104.

7. For examples in manuscripts, see Schiller, op. cit., figs. 617, 618; for sculpture, see figs. 632–640. Other French examples in sculpture of the naked soul of the Virgin in Christ’s arms are found the cathedrals of Laon (west portal), Chartres (north portal), and Mantes, (west portal).

8. Hayward, op.cit. p. 176.

9. Ibid.

10. For the Le Mans windows see: Louis Grodecki, Congrès archéoloque de France, 1961, pp. 59–99. For a complete description of the glass and the history of its restoration see: Catherine Brisac “Les vitraux du choeur,” in André Mussat, La cathédrale du Mans, Paris, 1981, pp. 107-126 and Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi, Les vitraux du centre de pays de la Loire, CVMA, Recensement, France, 2, Paris 1982, pp. 241–257.

11. Emile Mâle, L’art religieux du XIIIe siècle en France, 2nd ed., Paris, 1910, pp. 282–85 and 307-311; Grodecki, Congrès archéologuique, pp.78–79; and Brisac, op. cit., pp. 111–112.

12. CVMA, France, Recensement, 2, p. 248.

13. Eugène Hucher, Calques des vitraux pients de la cathédrale du Mans, Paris, and Le Mans, 1864, n.p. (Chapelle de la Vierge).

14. Cahn and Hayward, Radiance and Reflection, p. 178.

15. The dates of the construction are generally agreed. For an overview see André Mussat, La Cathedrale du Mans, Paris, Berger-Levault, 1981, pp. 81–102.

16. Papanicolaou, op. cit., passim.

17. Marc Thibout, “Vivoin,” Congrès archéologique de France, 119, 1961, 1961, pp. 246–254; and CVMA, France, Rescensement, 2, pp. 272–273.

18. Louis Grodecki in Vitraux de France du XIe au XVIe siècle, Paris, Musée des arts décoratifs, Paris, 1953, no. 21, p. 59; Grodecki, Congrés archéologique, 1961, p. 79; Brissac in Mussat, op.cit., p. 112; CVMA, France, Recensement, 2, pp. 213–335.

19. For overall and detailed views of both the Charlemagne window (Window 7, Delaporte, bay XXXVIII) and the Saint James the Greater window (Window 5, Delaporte, XXXVII), see Therosewindow.com.

20. Grodecki, Vitraux de France, no. 21, p. 59.

21. Ibid.

22. Jean Lafond “The stained-glass decoration of Lincoln Cathedral in the thirteenth-century,” The Archaeological Journal, 103, 1946, pp. 118–56.

23. Ibid, p. 153.

24. For architecture see, Robert Branner, Saint Louis and the Court Style in Gothic Architecture, Studies in Architecture, vol. VII, London, 1965, passim and for manuscript painting, see Robert Branner, Manuscript painting in the reign of Saint Louis, Berkely, 1977, especially chapter 1, “The making of illuminated manuscripts in 13th-century Paris.”

25. The Corpus Vitrearum Medii Aevi volumes both in France and America that have published material in monuments and museum collections much more fully. For the area around Paris see: Anne Granboulan, Louis Gradecki, Françoise Perrot, Les vitraux de Paris, de la region Parisienne, de la Picardie et du Nord-Pas-de-Calais, Paris, 1978. For a large museum collection in the US see: Jane Hayward, Mary B. Shepard, Cynthia Clark, English and French medieval glass in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2 vols., New York, 2003.

26. Virginia Chieffo Raguin, Stained glass in thirteenth-century Burgundy, Princeton, 1982.

27. Gercy is located near the town of Brie-Compte-Robert (Seine-et-Marne). Presently in the Cluny Museum are three Saint Martin panels, two panels from a Jesse Tree, panels from a Theophilus window, and fragments perhaps from a typological window. These final fragments include a Christ in Majesty, a blinded Synagogue, two border fragments with arms holding censers and a panel of musician angels. For the Jesse Tree see: Françoise Perrot, “Note sure les arbes Jessé de Gercy et de Saint-Germain-lès-Corbeil,” The Year 1200 Symposium, New York, 1975, 417–28. For the Gercy Saint Martin panels see: Raguin, Stained Glass in 13th-century Burgundy, Princeton, 1982, p. 42, note 3.

28. Ellen M. Shortell, “Dismembering Saint Quentin: Gothic architecture and the display of relics,” Gesta. 36 (1), 1997, pp. 32–47.

29. Charles T. Little, “Membra Disjecta: More Early Stained Glass from Troyes Cathedral,” Gesta, 20, 1981, 119–27. And CVMA, English and French medieval glass in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2 vols., New York, 2003, vol. 1, pp. 141–157.

30. Ann Trindade, Berengaria: In Search of Richard’s Queen, Dublin, 1999, chapter 5, “Widow,” p. 161.

Selected Bibliography

Hayward, Jane, and Mary Prevo. “The Pitcairn Collection.” Stained Glass. 76/1, Winter 1981–1982, p. 346, illus. in color.

Hayward, Jane, and Walter Cahn, et.al. Radiance and Reflection: Medieval Art from the Raymond Pitcairn Collection. Exhibition Catalogue, The Cloisters, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1982, pp. 175–178.

Papanicolaou, Linda Morey. “St. Martin and the Beggar: A Stained-Glass Workshop from the Lady Chapels of the Cathedrals of Lew Mans and Tours.” Studies on Medieval Stained Glass: Selected Papers from the XIth International Colloquium of the Corpus Vitrearum. United States, Occasional Papers 1, ed. Madeline Caviness and Timothy Husband, New York, 1985, pp. 60–69.

Photographic Credits

Unless otherwise noted in captions, the figures are from therosewindow.com, copyright Painton Cowen.

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox (12 times per year)? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.