Glencairn Museum News | Number 6, 2023

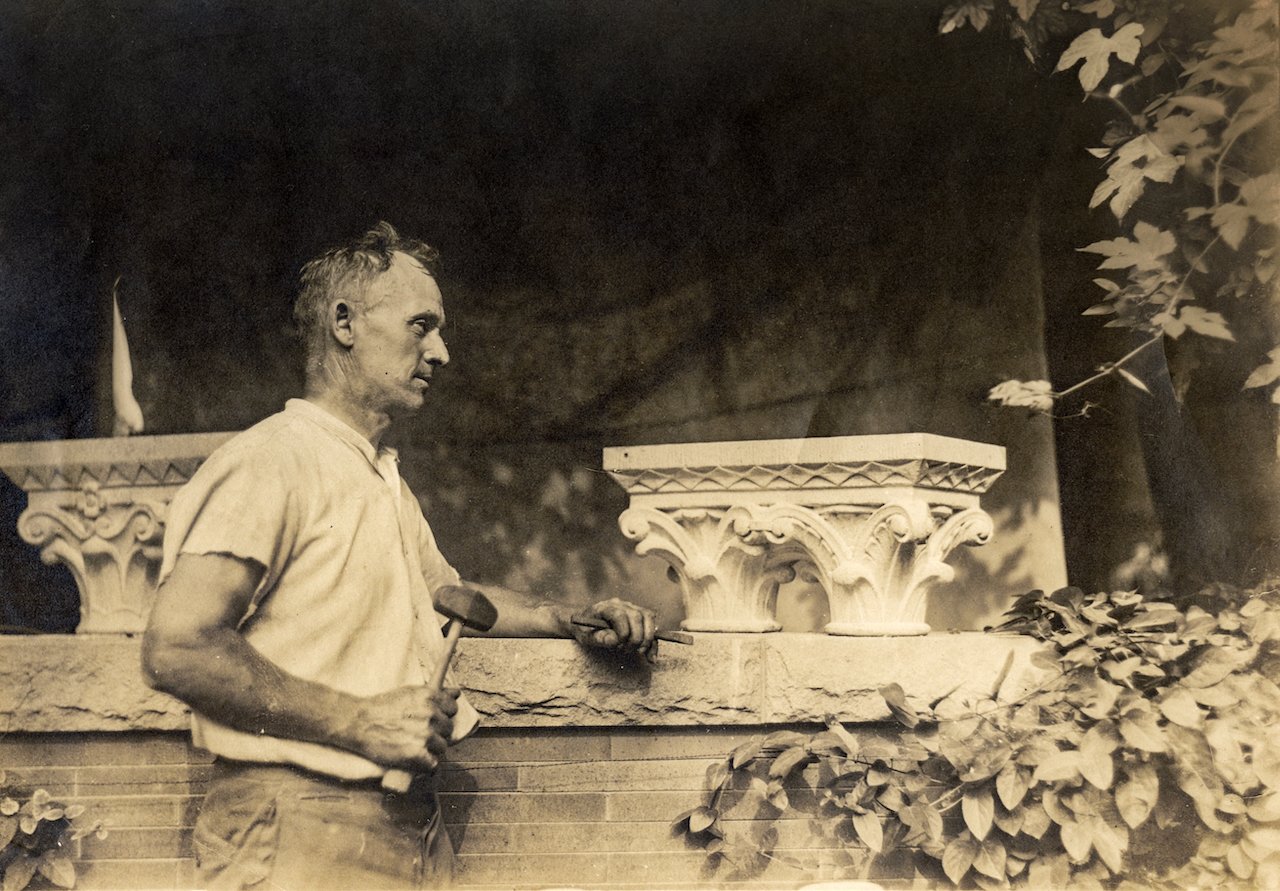

Benjamin Augustus Tweedale poses at Cairnwood, the Bryn Athyn residence of Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn, with stone carving tools beside a capital created for Bryn Athyn Cathedral (c. 1916).

Figure 1: Benjamin Tweedale posing with his stone carving tools outside one of the Bryn Athyn workshops.

Benjamin Tweedale’s stone carving expertise had a profound impact on the ornamentation of both Glencairn and Bryn Athyn Cathedral. His meticulous attention to detail and his fruitful artistic collaboration with his fellow craftsmen, especially the Italian stone carvers Pietro Menghi and Attilio Marchiori, resulted in works of art that continue to captivate visitors to this day.

Early Life and Career

Benjamin Augustus Tweedale was born in Philadelphia on August 31, 1868. He died on March 21, 1957, at the age of 88. His father, also named Benjamin, was born in Philadelphia in 1841 and served as a soldier during the Civil War. Benjamin senior’s father, Robert Tweedale, was born in England, and Robert’s wife, whose surname was Morrison, was born in Scotland.

In the 1880 census, Benjamin senior was listed as a “woodcarver.” Benjamin junior was employed by Raymond Pitcairn to work with wood as well as stone, suggesting that he may have acquired his carving skills from his father. When Benjamin Augustus passed away in 1957, his death certificate referred to him as a “sculptor.”

Tweedale began his work in Bryn Athyn in 1916 as a stone carver at Bryn Athyn Cathedral. While he was working in Bryn Athyn, and for at least the last 40 years of his life, he lived in a Victorian twin on Larchwood Avenue in West Philadelphia. Most likely Tweedale took the train to work each day, since at that time there was a stop at Bryn Athyn station. According to E. Bruce Glenn, the Pitcairns’ nephew, who knew Tweedale personally,

“This was the spirit that filled the air at Bryn Athyn, and made of a building operation a community of men, well over a hundred in number. Some of these lived in or near Bryn Athyn; most were part of the daily procession that trooped, chattering in several tongues, up from the Bryn Athyn station to the church hill in the morning and back at night to take the steam train to Philadelphia. In fact, this procession of workers was given official status by the railroad in July 1914, when that inexorable ruler, the train schedule, was altered to accommodate their evening transportation from work.

“How did these men feel about the work they were doing? Let one speak, in words carefully sought out years afterward to recapture the fact; and then let his action at the time speak to us for him. Benjamin Tweedale came in 1916 to work for three months as a carver . . . In his retirement he recalled the difference between this and other jobs he had done. ‘Others worked to meet a deadline for the profit of the contractor. They figured costs and ordered the job done. Here with Mr. Pitcairn excellence in the work was everything. He demanded truth and honesty, for these were what the church stood for.’” (Bryn Athyn Cathedral: The Building of a Church, 1971, 88–89)

Figure 2: A decorated wooden filing cabinet drawer serves as a container for some of Benjamin Tweedale’s stone carving tools.

Tweedale’s Stone Carving

Tweedale was not in charge of creating original designs for the decoration of Glencairn and Bryn Athyn Cathedral. The main responsibility for this rested with the architectural office and with Felice “Felix” Sabatino, who oversaw the modeling shop in Bryn Athyn and provided plaster casts for the stone carvers to use as references. Trial models, prior to being immortalized in stone and integrated into the actual structures, frequently underwent several revisions, all subject to the personal approval of Raymond Pitcairn.Tweedale and his fellow stone carvers, Pietro Francesco Menghi and Attilio Marchiori, were part of this creative process, as is clear from this 1922 letter from Pitcairn to Sabatino:

“I should like to have you make models for grape leaf design for the remaining chancel column capitals. . . . When you have worked out the models carefully, I would get the criticism of Meng[hi] and Tweedale and the other fellows, and then proceed to carve these capitals. . . .” (Raymond Pitcairn. Letter to Felice Sabatino. 23 October 1922. Glencairn Museum Archives, Bryn Athyn, PA).

Figure 3: Benjamin Tweedale “in action“ with a hammer and chisel beside a capital created for Bryn Athyn Cathedral (see also lead photo above, c. 1916).

Moreover, according to Tweedale, Pitcairn placed great importance on ensuring that his carvers grasped the spiritual meaning embedded within the sculptures they were tasked with creating:

“[Tweedale] described how, in preparing for symbolic carving from the Word, Raymond Pitcairn and he would read in the Scriptures the appropriate passages, and their spiritual interpretation in the Heavenly Doctrines, followed by suggestions and comparisons and the making of models, all leading to a steadfast expression of faith in stone. Asked about the artists’ attitude about the religious symbols with which their work was involved, [Tweedale] said that to work without understanding was to fail, and that he, and others, strove to grasp the spiritual import of their subjects” (Glencairn: The Story of a Home, 1990, 59, 62).

The collaboration between Tweedale and Menghi is best illustrated by the enduring presence of two prominent stone eagles positioned above the corners of Glencairn’s north porch. Affectionately referred to as “Benny” and “Pete” by the Pitcairns, these eagles were named after the craftsmen who carved them. Regrettably, the specific identities of Benny and Pete appear to have faded with time, as no one recalls which name corresponds to which eagle.

Figure 4: Stone eagles “Benny” and “Pete,” named after their sculptors, Benjamin Tweedale and Pietro Menghi, stand guard above Glencairn's north porch.

In general, there is scarce documentation available regarding the artists behind the carvings at Glencairn and Bryn Athyn Cathedral. None of the sculptures display the artists’ signatures. However, carvings credited to Tweedale are mentioned in several sources, such as E. Bruce Glenn’s typewritten notes on Glencairn’s Great Hall and his book on Glencairn.

One carving that has been identified as an example of Tweedale’s craftsmanship is a capital in the Great Hall situated on the left side of the Cloister door. This capital prominently incorporates two vital communities that the Pitcairn family sought to serve: their church and their school. The main figure on the left side of the capital shows the Woman Clothed with the Sun as described in the Book of Revelation (12:1). On the capital, the sun is prominently shown on the woman’s clothing, while the moon is beneath her feet. In New Church (Swedenborgian Christian) belief, this symbol represents the New Church itself.

The right side of the capital features a figure of a man adorned with a wreath on his head. He holds a scroll inscribed with the word “Academia”—that is, an “academy” or a “center of learning.” This reference may refer, not only to the importance of learning and education in general, but also to the official name of the educational institution located in Bryn Athyn—the Academy of the New Church. The Pitcairns, who were both graduates of the Academy, wholeheartedly supported this institution throughout their lives, and prior to her marriage to Raymond, Mildred served as a teacher at the Academy.

Figure 5: The main figure on the left side of this capital in Glencairn’s Great Hall shows the Woman Clothed with the Sun as described in the Book of Revelation (12:1). See also Figure 6, another side of the same capital.

Figure 6: The right side of this capital in Glencairn’s Great Hall shows a man adorned with a wreath on his head, holding a scroll bearing the word "Academia.” See also Figure 5, another side of the same capital.

Within the Cloister’s colonnade, twelve bird-themed capitals serve as another testament to Tweedale’s skill as well as the craftsmanship of other carvers. Each capital was carefully chosen to symbolize a distinct spiritual concept. According to E. Bruce Glenn, author of Glencairn: The Story of a Home (1990), the bird capitals in this cloister are spiritual symbols of “those ideals of the mind that lift us above worldly concerns as the flight of a bird draws our eyes from the earth” (179-180). Twelve species of birds are depicted on the capitals: peacock, dove, bird of paradise, stork, golden eagle, hen, swan, quail, flamingo, rooster, ibis, and pelican. In a note preserved in the Bryn Athyn Historic District Archives, dictated by Raymond Pitcairn on November 12, 1947, the flamingo, quail, and ibis capitals were carved by Tweedale.

Figure 7: The flamingo capital in Glencairn’s Cloister.

Figure 8: The ibis capital in Glencairn’s Cloister.

Figure 9: The quail capital in Glencairn’s Cloister.

Along the north wall of Glencairn’s Cloister, a twin-arched window provides a captivating view of the valley. A special bench, meticulously carved by Tweedale, was crafted from granite for Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn. This unique bench consists of two seats facing each other, with one armrest featuring a ram and the other a ewe. The motif of a ram, ewe, and lambs, symbolizing the importance of family, is a recurring theme throughout Glencairn.

Figure 10: Glencairn's Cloister contains a bench with two seats facing one another, featuring an armrest carved with a ram on one side and a ewe on the other.

Tweedale’s Woodcarving

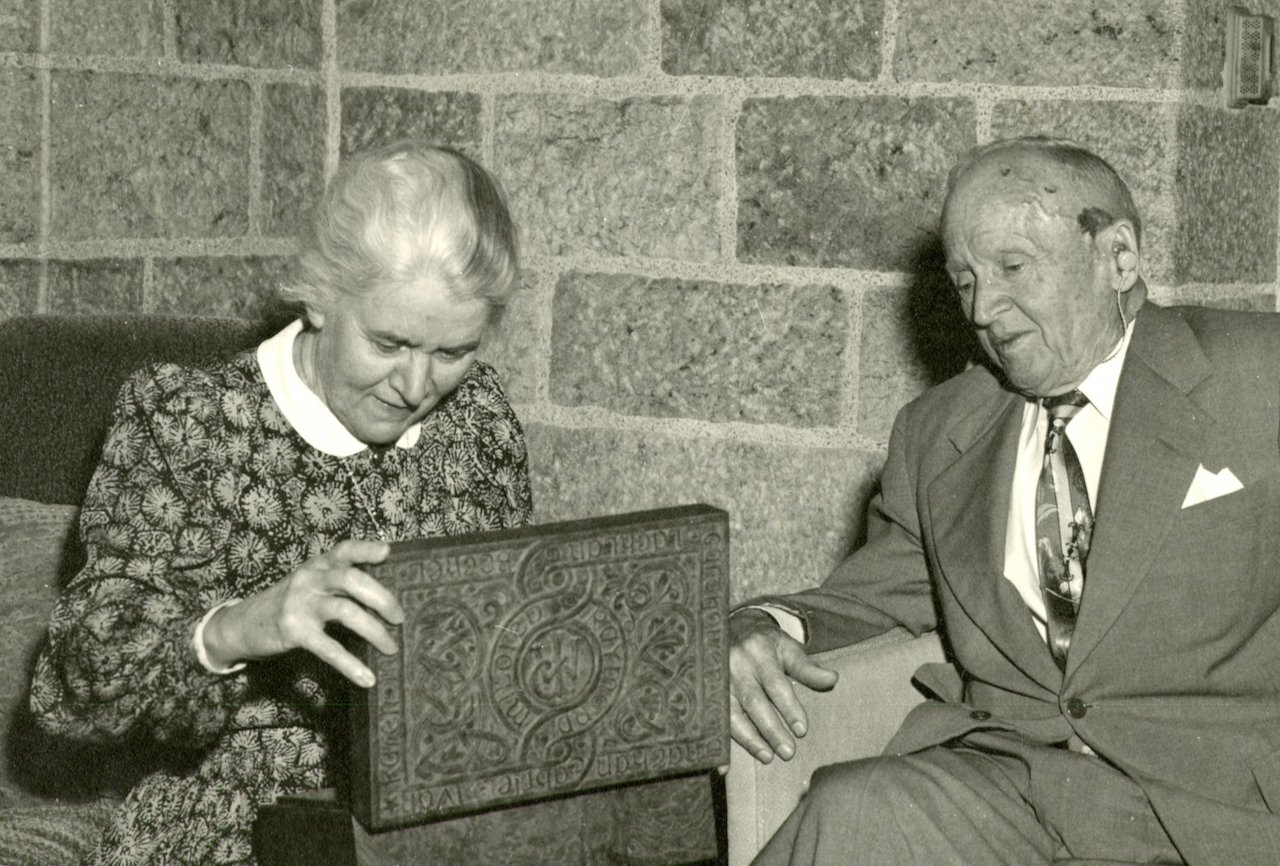

Tweedale, in addition to his stone-carving work on Glencairn’s architectural elements, crafted several personalized wooden gifts for the Pitcairn family. One of these was a rectangular jewelry box decorated with carvings on the lid, presumably commissioned by Raymond as a birthday surprise for Mildred. The box prominently displayed Mildred’s initials at its center, encircled by the names of Raymond and Mildred. Along the outer edge, the names of their nine children were intricately carved, arranged according to their ages. Invited to Glencairn, Tweedale was present for the presentation of this special gift to Mildred on her birthday, which fell on May 7, 1954. Commemorative photographs were taken during the occasion, and a week later Raymond sent Tweedale a letter accompanied by copies of these photos. In the letter, Raymond expressed his and Mildred’s delight with the jewelry box, stating that both of them had been enjoying it. Raymond also mentioned the possibility of Tweedale undertaking the carving of furniture for the Academy of the New Church’s chapel. Notably, Tweedale was 85 years old at this time.

Figure 11: This jewelry box, a present for Mildred’s birthday in 1954, was decorated with carvings on the lid by Tweedale. The names of the nine Pitcairn children are arranged according to their ages.

Figure 12: Tweedale was present for the presentation of the wooden jewelry box that he carved for Mildred in 1954 (see figure 11).

Several years later, to commemorate the couple’s 50th wedding anniversary in 1960, Tweedale carved another bespoke wooden jewelry box, this time fashioned in the shape of two doves. Pairs of doves as a symbol of marital love are a major decorative theme in Glencairn, where they appear frequently in wood, stone, and glass mosaic. The inscription along the top of the box reads: “Raymond & Mildred Dec – 29 – 1910 – 1960.” The inscription below, carved in Hebrew, is a verse from the Bible (Psalm 118:23): “This is the Lord’s doing; it is marvelous in our eyes.” The box was carved by Tweedale prior to his death in 1957 and subsequently presented to Raymond and Mildred by their children in 1960.

Figure 13: Tweedale carved this dove-shaped jewelry box to commemorate the Pitcairns’ 50th wedding anniversary in 1960. (See also Figure 14.)

Figure 14: Reverse side of the dove-shaped jewelry box. (See also Figure 13.)

Figure 15: The dove-shaped jewelry box, carved by Tweedale prior to his death in 1957, was presented to Raymond and Mildred by their children at Glencairn to commemorate the couple’s 50th wedding anniversary in 1960,

Dedication to Craftsmanship

Tweedale was known to be an extremely conscientious craftsman. While working on the Bryn Athyn Cathedral project in 1920, he accidentally broke off a small piece from a larger section of stone he was working on. Overwhelmed by distress, he left work for the day and went home. He then proceeded to write a note to Raymond Pitcairn, telling him, “if you wish me to return I will do so, if you do not, I thank you for the fair treatment I received while in your employ.” Pitcairn, who recognized Tweedale’s exceptional talent and commitment, was amused by the note, and naturally asked him to come back.

Many years later in retirement, after receiving a gift of flowers from Mildred Pitcairn, Tweedale wrote a thank you note. In this note he expressed something of what his years in Bryn Athyn had meant to him: “I am proud and grateful that it was my privilege to have even a small part in the work there, and the patient and constructive criticisms of Mr. Pitcairn, for whom we had the greatest respect and love, when I speak of we, I have in mind Menghi, Marchiori and myself.”

Tweedale’s reaction to the mishap mentioned above, and his genuine appreciation for the chance to work on the architectural projects in Bryn Athyn, exemplify his unwavering dedication to his craft. Together with colleagues Menghi and Marchiori, his stone carvings continue to inspire at Glencairn and Bryn Athyn Cathedral—a testament to their enduring legacy.

(CEG/KHG)

Would you like to receive a notification about new issues of Glencairn Museum News in your email inbox (12 times per year)? If so, click here. A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.