Glencairn Museum News | Number 7, 2023

Dating to the 5th century CE, this late antique sarcophagus has a fascinating history. Originally likely made to commemorate a Christian burial, it later found itself repurposed as a salt bath within a château. Eventually it left France and crossed the ocean to New York City, entering the Raymond Pitcairn collection in 1924.

This well-preserved piece (09.SP.1628) is carved in shallow relief on three sides (Figures 1–2). Flat columns divide the front face into three panels that contain a profusion of vegetation. Grape vines twine in each panel. The vines emerge from a central acanthus plant, which, in the central panel, is situated in a vase. The two short sides, also framed by columns, show ivy twisting out from the central acanthus plant, which, on the left side, also sits in a vessel. The back is uncarved.

Figure 1: Vegetal sarcophagus, 5th century, Glencairn Museum 09.SP.1628.

Figure 2: Vegetal sarcophagus, left and right side panels, 5th century, Glencairn Museum 09.SP.1628.

This biography presents a reconstruction of the history of this vegetal sarcophagus at Glencairn Museum in a series of chapters, as it were, moving backward chronologically from the present to the time in which the object was first created. Some chapters in the life story of this sarcophagus are well documented; others require more hypothesizing; and still others are currently blank due to a lack of evidence. The title given to each chapter calls attention to a prominent meaning the people who interacted with the sarcophagus at that time attributed to it. It is important to acknowledge, though, that the variety of meanings at play in any given period were more complicated than the distillations of values highlighted here.

In its lifetime, this sarcophagus has been (at least) a burial commemoration, a salt bath, a business opportunity, a collector’s item, and, most recently, a research puzzle.

Glencairn Museum Chapter, 1986–2023: A Research Puzzle

In 1986, Bret Bostock, a staff member at the recently opened Glencairn Museum, was involved in the discovery of this piece in the carriage house of the neighboring Cairnwood Estate (Figure 3). He recalled the experience in an interview:2

“I just remember going down there, back before the carriage house was set up. There were carriages in there but jumbled with all kinds of junk. . . . Somewhere along the line somebody noticed that in the corner, jammed in there, was a crate—a big crate. But nobody knew what was in it at all. So, it was really kind of this fun ‘hey, we are going to go down there, and we are going to uncrate this thing.’ Because who knows what might be in it. And so, it was really cool. I remember the moment: I was cranking it open and—oh my goodness—that looks like a big stone sarcophagus!”

Figure 3: Cairnwood’s carriage house.

When asked if it were possible that he had opened the original crate in which the object had been shipped to Bryn Athyn, and possible that the crate had never been opened previously, Bret replied:

“Yes, not only possible but likely. That is my opinion. It was an incredibly sturdy, clearly old crate. I think that there was, not straw, but a weird kind of packing material in there that seemed antique. It just was clear—it seemed clear to everyone involved—that this thing was sitting in Cairnwood since Raymond [Pitcairn] bought it and it was never opened. That was the overriding impression from all evidence at hand.”

Glencairn Museum, which had opened its doors to the public just a few years earlier in 1982, combined the collection of the Academy Museum (the museum of the Academy of the New Church schools) with the private collection of Raymond Pitcairn. Pitcairn’s collection had been bequeathed to the Academy of the New Church along with Glencairn itself after the death of Mildred Pitcairn, Raymond’s widow, in 1979.3 Glencairn had been Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn’s home, and when the building was given to the Academy of the New Church, the objects in the Pitcairn’s private collection were still located throughout the house, just as they had been during Raymond and Mildred Pitcairns’ lifetimes. As a result, in the Museum’s early years considerable attention was put toward identifying and cataloguing the objects that had been collected by Pitcairn. This sarcophagus, discovered unexpectedly, was one of a number of pieces in Pitcairn’s collection that required further research.

After Glencairn staff moved the sarcophagus with vegetal decoration to Glencairn’s cloister, their next step was to try to determine when and from whom Raymond Pitcairn had acquired it. To that end, staff members combed through hundreds of pages of correspondence between Raymond Pitcairn and various art dealers, now preserved in the Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Archives at Glencairn, and flagged any correspondence related to sarcophagi. In May 1987, Glencairn Museum director Martin Pryke explained the circumstances to Charles Little of the Medieval Department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, with whom Pryke had been dialoguing about the sarcophagus. Pryke sent Little a summary of correspondence between Raymond Pitcairn and art dealer Joseph Brummer in 1923–1924. Although this correspondence had initially appeared promising, Pryke noted that Pitcairn had written by hand “Penna. Museum” next to the entry for this sarcophagus in Pitcairn’s master collection list, Pitcairn’s means of indicating that the piece was loaned to the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Figure 4). Pryke ended his summary of evidence with the following: “I am forced to the conclusion (as a result of the last item [Pitcairn’s handwritten note]) that what this correspondence is talking about is not the sarcophagus which we now have in the Cloister, but the one which is now on loan to the PMA [strigiliated sarcophagus 09.SP.315]. This seems to bring us back to square one. So far we have not found any documentation for the one which we recently uncrated and put in the Cloister.”4 Although good work had been put into researching the piece, with the evidence available at the time it remained unclear how the vegetal sarcophagus had come to be in the carriage house and exactly what it was. Back to square one, as Pryke had said.

Figure 4: Excerpt from notebook, “R.P. Antiques Catalogued by Dealers” (Glencairn Museum).

Although Stephen Morley, the next Museum director, remained interested in the piece and identified several useful comparisons in other collections, the vegetal sarcophagus at Glencairn remained a research puzzle because the information available could not definitively connect this object with a particular purchase by Pitcairn. The sarcophagus was eventually moved to museum storage, where it currently resides.

We are now in a better position to address the question of how this vegetal sarcophagus came to be in a crate in the Cairnwood carriage house, thanks to information from the Brummer Gallery Records located in The Cloisters Archives of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. As explained in more detail below, the Brummer Gallery Records provide proof that the correspondence the Glencairn staff had previously identified in the Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn archives was indeed about the vegetal sarcophagus, despite the handwritten note by Pitcairn.

The Pitcairn Chapter, 1923–1924: A Collector’s Item

Joseph Brummer (1883–1947), a prominent dealer of medieval and other art in the early 20th century with offices in New York City and Paris, was one of the art dealers from whom Raymond Pitcairn frequently purchased (Figures 5–6).5, Brummer kept business records of key information about the acquisition, movement, and sale of art on object cards. The Brummer Gallery Records preserve object cards for two different sarcophagi that Raymond Pitcairn purchased from Brummer. These cards provide information that clarifies which correspondence between Pitcairn and Brummer relates to the vegetal sarcophagus at Glencairn Museum.

Figure 5: Joseph Brummer. (“Joseph Brummer, Kaiden Studios, NY” from The Brummer Gallery Records, The Met: Watson Library Digital Collections.)

Figure 6: Raymond Pitcairn. (“Formal Portrait of Raymond Pitcairn” (RMP_PRI_0107), Bryn Athyn Historic District Archives.)

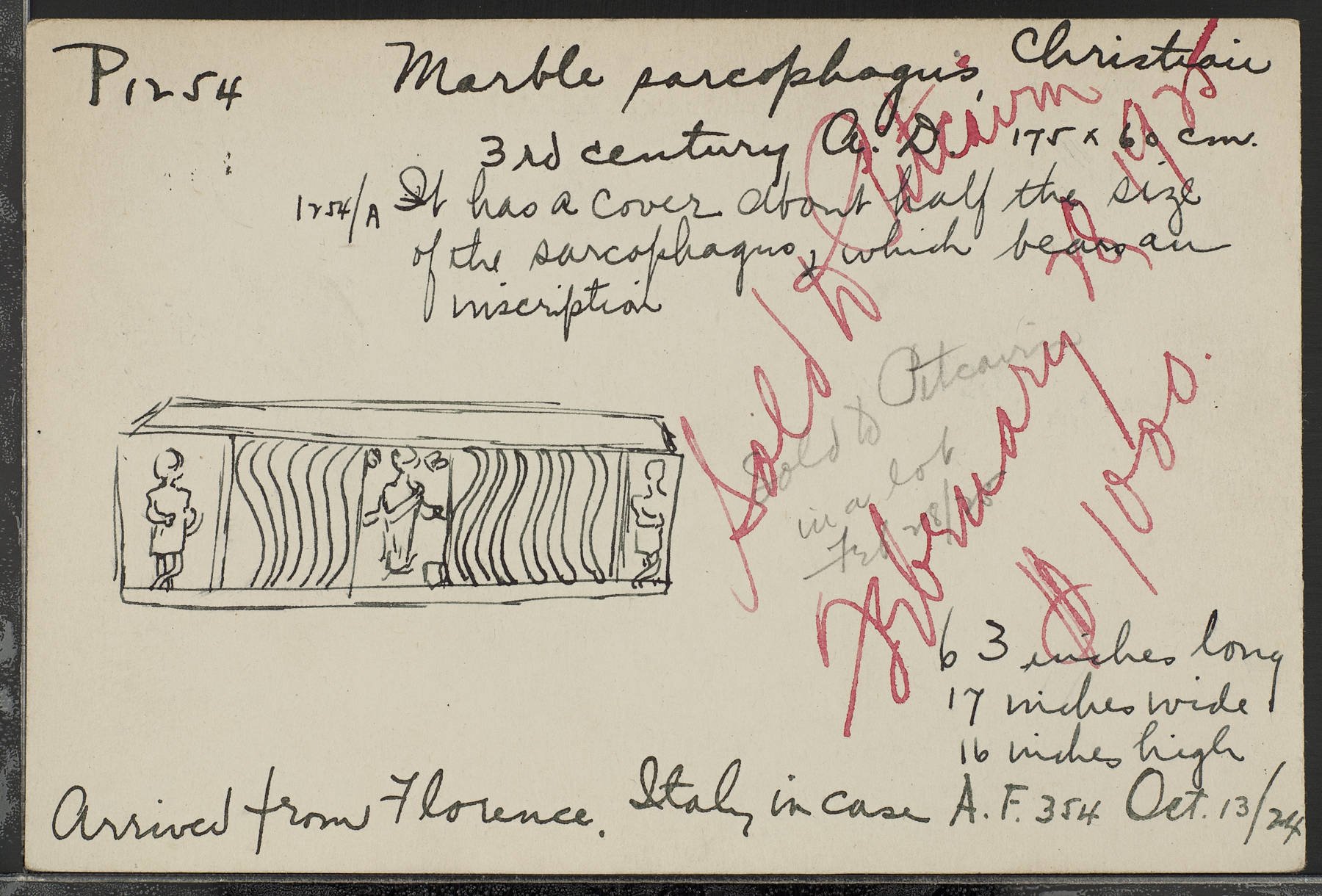

Card P811 (Figure 7) documents an object labelled as “Sarcophagus in marble decorated on three sides with leaf design,” a description that aligns with the vegetal sarcophagus.6 Brummer recorded in light pencil on the left “Sold to Pitcairn December 8, 1923 $1900.” A little later in red Brummer wrote overtop the center of the card “Sold to Pitcairn February 1, 1924 $1900.” (Letters in the Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers, discussed below, will explain why two sales dates are recorded.) Card P1254 (Figure 8) for a “Marble sarcophagus, Christian” has a drawing of a strigilated sarcophagus with three figures. On it Brummer wrote in red: “Sold to Pitcairn February 28, 1925 $1000.” The sketch confirms that the strigilated sarcophagus that Pitcairn loaned to the Philadelphia Museum of Art was purchased from Brummer in 1925. Pitcairn must have written “Penna. Museum” next to the wrong entry on his master collections list, accidentally making the notation beside the sarcophagus purchased in 1924 rather than one purchased in 1925.7

Figure 7: Brummer Object Card P811. (“P811 : Sarcophagus, marble, leaves” from The Brummer Gallery Records, The Met: Watson Library Digital Collections.)

Figure 8: Brummer Object Card P1254. (“P1254 : Marble, sarcophagus, Christian, 3rd C., cover, inscription” from The Brummer Gallery Records, The Met: Watson Library Digital Collections.)

As the object cards make clear, Pitcairn’s 1923–1924 correspondence with Brummer concerning a sarcophagus must refer to the vegetal sarcophagus. Details in these letters shed light on Pitcairn’s activities as a collector, Brummer’s strategies as a dealer, and the context in which Pitcairn acquired the vegetal sarcophagus.

According to the correspondence, Raymond Pitcairn first saw the vegetal sarcophagus in late 1923. At that point in time, Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn were living in Cairnwood, the beaux-art style home that Raymond’s parents, John and Gertrude Pitcairn, had built in the 1890s. Raymond Pitcairn had inherited Cairnwood after his father had died in 1916. (His mother had passed away previously in 1898.) Raymond Pitcairn also picked up the mantle from his father of overseeing the construction of Bryn Athyn Cathedral. Although the Cathedral was dedicated in 1919, work on its stained glass only commenced in 1922. Pitcairn began collecting medieval art in earnest in 1921 to provide models and inspiration for the craftsmen working on the Cathedral. He also began collecting a variety of other items at this time, purchasing from a number of dealers, including Joseph Brummer.

On November 23, 1923, Brummer reached out to Pitcairn to alert him to an opportunity to acquire a sarcophagus. He wrote (Figure 9):

Figure 9: Letter from Joseph Brummer to Raymond Pitcairn, November 23, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

“There is a large 10th century sarcophagus in marble which has just arrived, that I should like to show you. It is still packed in the case, standing in front of our building and weighs about a ton, and I do not know whether it will go into the basement. This sarcophagus is a well known piece, having been described in the Tour de France. It came from the Chateau de Massanès, and some people think it is of the 8th century. It is a very beautiful thing and I would want you to see it when you are in New York.” 8

Pitcairn replied four days later, on November 27, that he would pay Brummer a visit when he was in New York. Interestingly, in his note he included an inquiry about another piece: “By the way you mention nothing about the little figurine of Socrates. If the price is fair, I should be interested in this terra cotta.” 9 To this Brummer replied the same day: “With reference to the terra cotta figure of Socrates, I am sorry but at this moment it is up at the Metropolitan Museum where it will be presented before the purchasing committee at their meeting December 8th. Should the Museum decide not to buy it, I will be glad to hold it at your disposition.” 10 I’m calling attention to the exchange about this Socrates terracotta because it provides a window into the context in which Pitcairn was considering buying the vegetal sarcophagus. Reference to the terracotta Socrates will appear again later in the correspondence between Brummer and Pitcairn.

After Pitcairn visited Brummer’s establishment in New York, Brummer followed up with him about it. On December 5, Brummer wrote, trying to create competition between Pitcairn and the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

“As to the sarcophagus, I haven’t shown it to anyone as yet as I wanted your opinion of it. It would be a great favor to me if you could let me have your answer by return mail as I had an order from the Metropolitan Museum of Art to be on the lookout for an early Christian sarcophagus of which they have none in the Museum. Therefore should you not wish to buy it, I would like to show it to them.” 11

Pitcairn remembered his recent loss of the Socrates terracotta to the Met, and, perhaps not wanting to let the sarcophagus get away to the Met as well, Pitcairn sent the following response two days later (Figure 10):

Figure 10: Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Joseph Brummer, December 7, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

“I have received your letter and in reply wish to assure you that I shall take the early Christian sarcophagus. I though[t] I made this clear in the basement when you asked me the question. I suppose that my statement later in the day that I did not really know what I would do with it may have aroused some doubt in your mind.”

He went on to take Brummer to task:

“With regard to the little terra-cotta statue of Socrates, I am really surprised at your treatment of me. When I returned and spoke to my brother [Theo Pitcairn] he said that it was made absolutely clear that I had purchased this object and reminded me that it was given to Mrs. Tuma to pack so that I could carry it back with me but at the last moment, I was obliged to leave for my train and it was agreed that this with the other two objects would be sent.”12

Brummer replied on December 11:

“I am glad that you have bought the early Christian sarcophagus. It is really a very fine and interesting object. I have already given it to the packer and hope that it will reach your studio in a few days. Enclosed please find bill. As to the terra-cotta figure, I am sorry that I did not understand that you intended to buy it.”13

Pitcairn concluded this discussion of the sarcophagus with a short reply the next day: “Will you kindly hold the sarcophagus until I send shipping instructions?”14

In sum, in December 1923 Pitcairn had agreed to purchase an “early Christian” sarcophagus from Brummer, a decision that aligns with the initial sales notation of December 8 that Brummer made on his object card for the piece (Figure 7). Pitcairn send payment for $1900 on January 31, 1924, the day before the second notation that Brummer made on his object card.15 Pitcairn had had to reassure Brummer of his intention to buy the sarcophagus when it seemed like Brummer might sell it to the Met, as he had the Socrates figure. The letters also highlight that Pitcairn did not have a specific plan for this piece, as he had mentioned to Brummer that he “did not really know what [he] would do with it.” Interestingly, when Pitcairn does ultimately buy the sarcophagus, he immediately requests that Brummer store it in New York.

There it stayed for several months. On April 1, 1924, Pitcairn received a bill for four months of storage,16 and on April 9th he sent the following instructions to Brummer:

“I think, all things considered, I better have the object delivered to Bryn Athyn and I will find some place to store it. Will you kindly attend to this for me?”17

And so in the spring of 1924, the sarcophagus made its way from storage in New York to storage in Bryn Athyn. It is likely that the shipping crate was placed in the Cairnwood carriage house and remained there unopened until Bret Bostock uncrated it in 1986. How could it be that Pitcairn never opened it?

Placing the sarcophagus purchase in the larger context of Pitcairn’s collecting history suggests an explanation. Pitcairn’s master collections list, which includes objects ranging from medieval and ancient art, to art from other regions and periods, antique furniture, 18th-century pewter items, and fabric, documents each of the purchases Pitcairn made from when he first started collecting in 1916 through 1939, when he and his family moved into Glencairn. Figure 11 shows the number of purchases made each year from 1916 to 1925.

Figure 11: Number of purchases Raymond Pitcairn made by year between 1916 and 1925 as recorded in his master collections list. Note that each purchase usually included multiple items.

As the timeline indicates, Pitcairn had begun his collecting in earnest in 1921, following his success in acquiring numerous pieces of medieval stained glass at auction in January 1921, and the amount he purchased increased substantially in subsequent years. In 1924, when Pitcairn purchased the vegetal sarcophagus and brought it to Bryn Athyn, he and his family were living in Cairnwood. Glencairn did not yet exist; construction on the building would not commence until 1928. It is no wonder that in the early 20s Pitcairn begins talking about the need for a “little studio,” as he termed it at that time, to house his rapidly growing collection.

Looking more closely at the period around the time that the sarcophagus he purchased from Brummer was shipped to Bryn Athyn, the master collections list records a number of purchases in March and April 1924:

- a 12th-century relief of Christ from Demotte (purchased March 3, 1924)

- a 15th-century candlestick, a Greek female head, two columns (one medieval and one Byzantine), and a wooden statue of Christ from Brummer (purchased March 7, 1924)

- four stone reliefs, four stone capitals, a wooden crucifixion, a wooden statue of the virgin, and a stone head, all medieval, from Demotte (purchased March 11, 1924)

- a pair of candlesticks, a pewter plate, and two pewter shakers from H. Douglass Curry (purchased March 19, 1924)

- a head from Crete from Karkudas (purchased March 19, 1924)

- a Jacobean oak cabinet from Richard Lehne (purchased March 19, 1924)

- two 13th-century capitals from Kelekian (purchased March 20, 1924)

- two 13th-century marble reliefs from P. Sestieri (purchased March 26, 1924)

- 49 pieces of 13th-century glass from Bacri Frères (purchased March 28, 1924)

- two Windsor chairs, a Jacobean table, a coffer, and a Jacobean dresser from H. Douglas Curry (purchased April 10, 1924)

- two Persian tiles from Kelekian (purchased April 20, 1924)

The number of purchases Pitcairn made at this time is significant, each of which involved correspondence back and forth between Pitcairn and the sellers. Pitcairn did not have much space in Cairnwood for all of these pieces.

In addition to the challenge presented by the volume of objects he was acquiring, Pitcairn was dealing with a headache related to his purchase of 49 pieces of medieval glass from Bacri Frères, which had been shipped to Pitcairn from Paris. 18 On March 18th, 1924, Pitcairn’s secretary wrote to O.G. Hampstead & Son in Philadelphia:

“Attention Mr. McGillan Pursuant to our telephonic conversation of this morning, will you kindly send us a copy of the Consular Invoice, covering shipment of two cases of glass from Bacri Frères, Paris, France, via the President Polk. We will appreciate any advice you may give us concerning the deplorable condition of the glass in which it arrived in Bryn Athyn.” 19

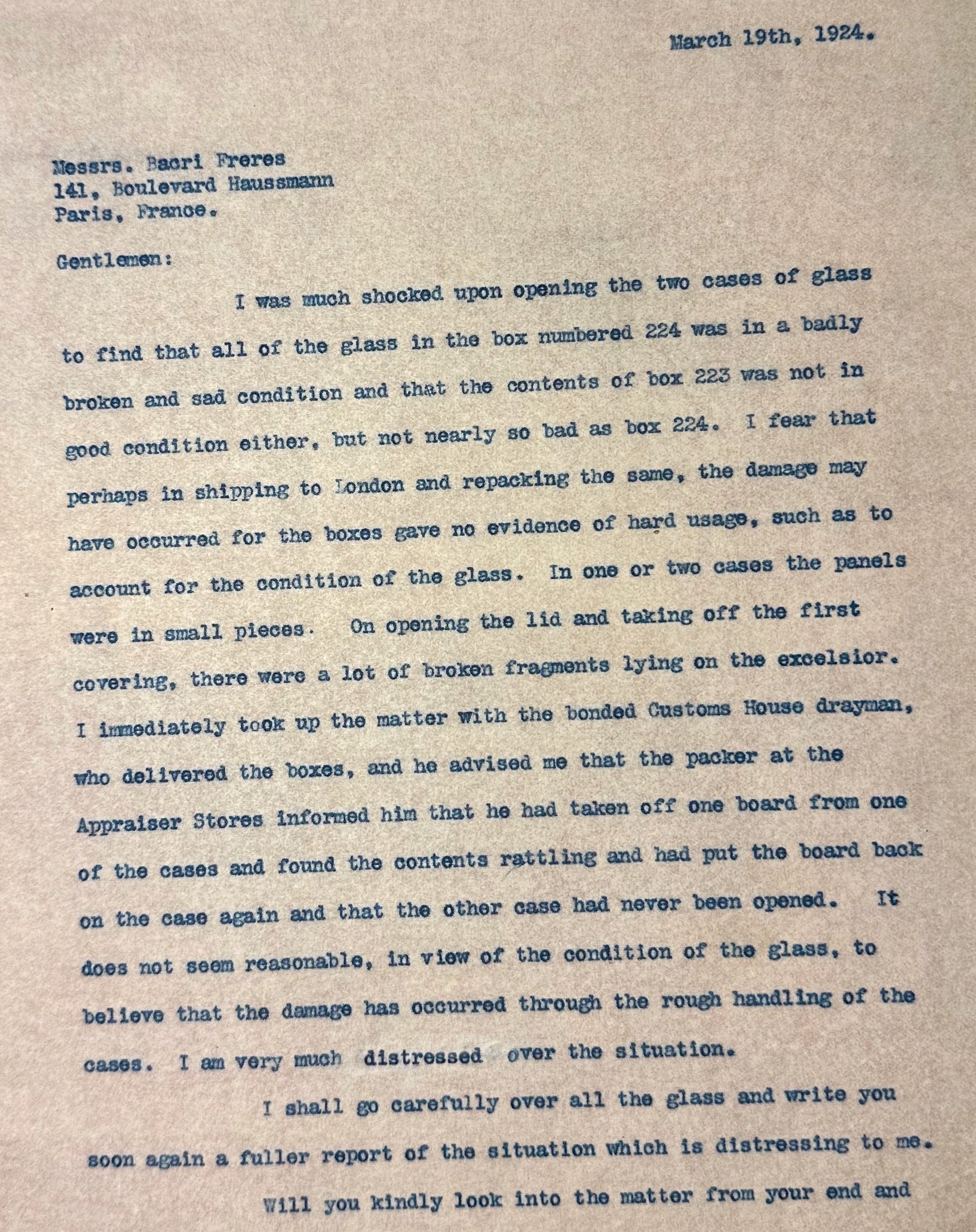

The next day, March 19th, Pitcairn wrote to Tobias & Company of New York inquiring about the insurance company handling the shipment, and to Bacri Frères reporting the damage (Figure 12). He begins:

Figure 12: First page of letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Bacri Frères, March 19, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

“I was much shocked upon opening the two cases of glass to find that all of the glass in the box number 224 was in a badly broken and sad condition and that the contents of box 223 was not in good condition either, but not nearly so bad as box 224. . . .”

And near the end of the letter he reiterates:

“I am very much distressed over the situation. I shall go carefully over all the glass and write you soon again a fuller report of the situation which is distressing to me.”20

Pitcairn continued to pursue the matter, and communications between Pitcairn and the customs house brokers, freight company, and Bacri Frères in late March and early April are preserved in the Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn archives.

It seems reasonable to conclude that, given the substantial number of purchases Pitcairn was making and the need to investigate the damaged shipment of stained glass from Bacri Frères, a sarcophagus that had already been in storage for several months was not the focus of Pitcairn’s attention when it arrived in Bryn Athyn in early April 1924. It is plausible that the piece was put aside at this time, and that when Pitcairn finally moved in to Glencairn years later in 1939, the crate containing the sarcophagus remained forgotten in its corner in the Cairnwood carriage house.

The Brummer Chapter, 1923: A Business Opportunity

The Brummer object cards, discussed above, not only record information about Brummer’s sales; they also include information about where Brummer had acquired his pieces. The object card for the vegetal sarcophagus (Figure 7) chronicles the sarcophagus’ journey from Paris to New York a few weeks before Brummer first wrote to Raymond Pitcairn about it. The card also records when and from whom Brummer purchased the piece. At the bottom, Brummer made the following notation in pen: “Bought from Lelong du Dreneuc through Paul Toussaint Oct. 15, 1923 for 15,000 frcs. Sent money to Pottier Oct. 15, 1923.” Then, above it, he wrote in pencil, “Oct 15/23 wrote Pottier to send it to America.” And above that in pen: “Received from Paris Nov. 11, 1923.” The other side of the card (the verso) provides a breakdown of the financial transaction between the New York and Paris offices.21

This card is a business record, documenting the monies outgoing and incoming in relation to the piece. Brummer paid 15000 francs or $924.75 for it. He then sold it to Pitcairn for nearly $1000 more—$1900. For Brummer, the card attests, the sarcophagus was a business opportunity, a source of revenue.

Moving back in time before Brummer’s purchase in 1923 the direct trail peters out.22 Here is the first chronological gap in the available records for the history of the vegetal sarcophagus. Piecing together earlier chapters in the sarcophagus’ life story, then, involves more hypothesis and likelihood, since there currently is no documentation about the location of this particular piece immediately prior to Brummer’s acquisition of it in 1923.

The (Likely) Massanès Chapter, 1776–1920: A Salt Bath

Two statements Brummer made in letters to Pitcairn offer a clue about the sarcophagus’ earlier history. When Brummer first reached out to Pitcairn about the sarcophagus on November 23, 1923, a few weeks after the sarcophagus had made its way from Paris to New York, he described it in this way (Figure 9):

“This sarcophagus is a well known piece, having been described in the Tour de France. It came from the Chateau de Massanès. . . .”23,

He repeats this assertion that the sarcophagus was originally from the Château de Massanès a few months later. In a letter dated April 7, 1924, Brummer wrote to Pitcairn:

“I have just found among my papers a page torn from a French guide book describing the Sarcophagus, which you bought from me recently. This description reads: “Beau sarcophagus chrétien en marbre blanc, sembable à celui de Moissac, dans une cave du château de Massanès. [Beautiful Christian sarcophagus in white marble, like the one from Moissac, in a basement of the château de Massanès.]”24

Brummer enclosed with his letter the guidebook page he referenced, removed from the book (Figure 13). How much credence should be given to Brummer’s assertion that the sarcophagus he sold to Pitcairn is the one from the Château de Massanès? Is this attribution verifiable? To answer these questions, we will first examine what is known elsewhere about a sarcophagus from the Château de Massanès, and then we will compare that piece with the sarcophagus at Glencairn.

In 1872, A. Lagrèze-Fossat published an article about a sarcophagus from the Château de Massanès (Figure 14).25 The details that Lagrèze-Fossat provided tally well with those in the guidebook from Brummer. Lagrèze-Fossat records that the piece is from Beauville (Lot-et-Garonne), as does the guidebook. He reports that he saw the sarcophagus in the basement of the Château de Massanès, an eclectic building, with some parts Romanesque, others 14th century, and most elements more modern, starting in 1776. The guidebook makes a similar assertion, noting that the château dates in large part to the 18th and 19th centuries, with fortified parts of the 13th, 19th, and 17th centuries.26 The article even has a lengthy comparison of the sarcophagus from Massanès with one from Moissac, the same comparison that the guidebook highlights. Based on the similarities in description, the sarcophagus in the guidebook used by Brummer appears to be the same as the sarcophagus published by Lagrèze-Fossat.

Figure 13: Guidebook page that Joseph Brummer enclosed with a letter to Raymond Pitcairn, April 7, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers. The section Brummer referenced was marked in pencil.

Figure 14: First page of article by A. Lagrèze-Fossat. 1872. “Le Sarcophage de Massanés.” Bulletin archéologique et historique de la Société archéologique de Tarn-et-Garonne, 2: 353–357.

Is the vegetal sarcophagus now at Glencairn this sarcophagus from the Château de Massanès? Unfortunately, Lagrèze-Fossat’s article does not include any photographs that would allow for a definitive identification. It does, however, provide a detailed description of the piece.

A comparison of the sarcophagus from the Château de Massanès, as described by Lagèze-Fossat, and the Glencairn sarcophagus shows that the iconography matches and, perhaps even more compelling, the two sets of measurements are within a couple of centimeters of each other (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Comparison between the Château de Massanès sarcophagus and the Glencairn sarcophagus.

In addition, Lagrèze-Fossat notes that the remains of iron clamps used to attach the lid to the sarcophagus box are very apparent on the sarcophagus from the Château de Massanès. The Glencairn piece likewise shows cuttings and staining from metal in three places of the top front panel (Figure 1 and Figure 16). The close alignment of the descriptions and measurements suggests that the Glencairn piece is most likely the sarcophagus from the Château de Massènes, just as Brummer claimed it was.

Figure 16: Close-ups of metal staining in two locations on the interior of the front face, Glencairn Museum 09.SP.1628.

The sarcophagus from the Château de Massanès is also included in three catalogs of sarcophagi from late antique south-west Gaul.27 The entry for it in the catalogue produced by Brigitte Briesenick in 1962 contains a notation that the sarcophagus was in Massanès until 1920, and at the time of her writing was in England in a private, unknown collection. Briesenick did not indicate how she came by this information. Based on the evidence laid out here, it seems probable that the sarcophagus did not go to a private collection in England, but instead went to the private collection of Raymond Pitcairn in the United States when it was sold by Brummer to Pitcairn in 1924.

What had the sarcophagus been doing in the basement during its time at the Château de Massènes? Lagrèze-Fossat explained that the sarcophagus was made from the white marble of the Saint-Béat quarry, but its color had been altered by fatty deposits on the interior and exterior because the piece had been used as the salt bath of the house, presumably used to cure meat.28 It may be that the hole cut into the bottom corner of the Glencairn sarcophagus relates to its time of use as a salt bath for the Château de Massènes (Figure 17).

Figure 17: Hole cut into bottom corner, Glencairn Museum 09.SP.1628.

The South-West Gaul Chapter, 5th century: A Burial Commemoration

The final chapter presented here looks at the early life of the vegetal sarcophagus at Glencairn. This chapter takes place in southwest France more than a thousand years before the previous chapter. The approach taken in this chapter differs from the previous ones because we do not have any documentation for the original context of Glencairn’s sarcophagus in particular.29 Instead of discussing this specific object, this chapter instead considers the corpus of material to which the Glencairn piece belongs.

The Glencairn sarcophagus is one of a group of sarcophagi that were produced in the south-west region of France primarily in the 5th-century CE, now known as the South-West Gaul type.30 One striking characteristic of this corpus is how prevalent vegetal decoration is in it. Vegetal designs are found on about 47% of examples of this type of sarcophagus, more frequently than any other iconographic category in this corpus, such as strigilated designs found on about 27% and figural scenes found on about 22%.31 The vegetal imagery on the Glencairn sarcophagus, then, represents a widespread motif that is characteristic of this corpus.

The vegetal design consists of different renditions of grape vines, acanthus, and/or ivy. Panel divisions on the sarcophagi can vary (Figures 18–19). Columns are very common at the edges of the carved faces and sometimes are used as panel dividers, and the shape of the sarcophagus box is distinctive, with sides that slope outward from bottom to top. A number of examples include with the vegetal imagery the Christian chi-rho (a symbol consisting of the first two Greek letters in the name Christ), along with an alpha and omega (the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, sometimes used in Christian scripture to refer to God). Occasionally animals, especially birds, appear in the vegetation (Figures 20–21). No two sarcophagi in the corpus are identical.

Figure 18: Vegetal sarcophagus, Musée Saint Raymond Ra 769, Toulouse. (Photo from Musée Saint Raymond, Palladia.)

Figure 19: Vegetal sarcophagus, Musée Saint Raymond Ra 13, Toulouse. (Photo from Musée Saint Raymond, Palladia.)

Figure 20: Vegetal sarcophagus, Crypt of the Basilica of Saint Seurin, Bordeaux. (Photo by author.)

Figure 21: Vegetal sarcophagus, Musée Saint Raymond 2000 44 14, Toulouse. (Photo from Musée Saint Raymond, Palladia.)

Although the piece from the Château de Massanès had been compared with the sarcophagus from the nearby site of Moissac (Figure 22), a closer iconographic parallel for the Glencairn sarcophagus comes from Toulouse (Figure 23).

Figure 22: Vegetal sarcophagus, Abbaye Saint-Pierre, Moissac. (Photo from Wikimedia Commons.)

Figure 23: Vegetal sarcophagus, Musée Saint Raymond Ra 14, Toulouse. (Photo from Musée Saint Raymond, Palladia.)

The vegetal imagery on the sarcophagi of southwest Gaul has often been interpreted as having Christian resonance. For example, the grapevines, which are very common, are sometimes thought to evoke the eucharist or to allude to Jesus’ metaphor in the Gospel of John (15:1) “I am the vine, you are the branches.”32

Sarcophagi of the South-West Gaul type get their name from the fact that they were produced in southwest France and were made of local stone, many of marble from the Saint Béat quarries in the north central Pyrenees. On the map in Figure 24, the blue pins show locations where sarcophagi of the South-West Gaul type with vegetal iconography have been found. The primary period of production is the 5th century.

Figure 24: Map showing locations of late antique sarcophagi with vegetal decoration.

Zeroing in on the southwest region of France (Figure 25), many are found near the Garonne river, which flows from the north central Pyrenees to Toulouse (underlined in blue), and then turns northeast to Bordeaux (underlined in blue). Beauville (underlined in red), the location of the Château de Massanès and the likely place where the Glencairn sarcophagus is from, is north of the Garonne river mid-way between Toulouse and Bordeaux. Other sarcophagi are located along part of the Aude river (not marked on the map), which starts in the Pyrenees south of Carcasonne, and, at Carcasonne, turns east and runs past Narbonne (underlined in blue) to empty into the Mediterranean. The sarcophagi also fan out along the Mediterranean coast. This corridor from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, from Narbonne to Toulouse and Bordeaux, was a much frequented economic and travel route, with shipping along the rivers (with just a short span overland between them) and a major Roman road that had been in use for more than half a millennium prior the 5th century. Due to the movement of things, people, and ideas along this corridor, this region was a cultural zone in late antiquity.33 Sarcophagi with vegetal decoration were popular in this particular cultural region of Gaul.

Figure 25: Map of southwest France showing the locations of vegetal sarcophagi of the South-West Gaul type.

Because there are no inscriptions on any of these sarcophagi, we do not have evidence for who was interred and commemorated in them. The expense of the stone and carving, however, point to use by the elites of the region, whether Gallo-Roman aristocrats or Visigothic rulers.

There is also a paucity of information about the primary archaeological context of this material, since these sarcophagi were very frequently reused during the medieval and later periods. Speaking in generalities, a number of the sarcophagi can be broadly associated with late antique cemeteries in which stood a Christian funerary basilica or mausoleum, which subsequently developed into a larger church during the Middle Ages. Examples include the Basilica of Saint Seurin in Bordeaux,34 the Basilica of Saint Sernin in Toulouse,35 and the Church of Saint Paul Serge in Narbonne (Figure 26).

Figure 26: Sarcophagi in the crypt of the Church of Saint Paul in Narbonne. The decorated lid of a vegetal sarcophagus is visible. (Photo by author.)

In late antiquity, as Christianity came to be the dominant religion in this region, numerous examples of such Christian funerary basilicas appeared in cemeteries, where they served to create, in the words of Bailey Young, a “new Christian topography” that served to “honor…the memory of the revered dead.”36 The vegetal sarcophagi of southwest Gaul, like Glencairn’s sarcophagus, were part of the developing ways that the Christian aristocratic elite of southwest Gaul were commemorating the dead in late antiquity.

Conclusion

In this object biography of Glencairn piece 09.SP.1628, we have considered the following chapters in its life story:

- The South-West Gaul Chapter, 5th century: when the sarcophagus likely commemorated a Christian burial;

- The (Likely) Massanès Chapter, 1776–1920: when the sarcophagus was built into the basement of a château and came to be used as a salt bath;

- The Brummer Chapter, 1923: when Joseph Brummer’s business purchased the sarcophagus, and the Paris office shipped it to New York to sell;

- The Pitcairn Chapter, 1923–1924: when, after Joseph Brummer called it to the attention of Raymond Pitcairn, Pitcairn purchased it for his collection, and, in April, 1924, shipped the sarcophagus from New York to Bryn Athyn, where it was stored in the Cairnwood carriage house;

- The Glencairn Museum chapter, 1986–2023: when, after the sarcophagus was rediscovered by Glencairn staff, it presented a research puzzle to staff—what was it and why was it in the Cairnwood carriage house?

Glencairn staff hope to place this sarcophagus on exhibit in the near future, with the goal that during the next chapter in its life story this interesting vegetal sarcophagus will educate and delight museum visitors as they contemplate its multi-faceted history.

Wendy Closterman, PhD

Associate Curator, Glencairn Museum

Professor of History and Greek at Bryn Athyn College

Endnotes

1. On object biography see, for example: Kopytoff 1986; Gosden and Marshall 1999; Joy 2009; and Drazin 2020.

2. Interview with Bret Bostock, March 1, 2023.

3. On the founding of the Academy Museum, see Gyllenhaal 2017. On Raymond Pitcairn’s collecting and the construction of Glencairn, see Gyllenhaal 2022.

4. Letter from Martin Pryke to Charles Little, March 5, 1987. Curatorial Files “09.SP.1628.” On Pitcairn’s numerous loans to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, see Hinton 2017. Sarcophagus 09.SP.315, which had been on loan to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for many decades, is now on display in Glencairn Museum’s Roman gallery.

5. Pitcairn’s first purchases from Brummer date to January 23, 1922. On Joseph Brummer, see Brennan 2015.

6. “P811: Sarcophagus, marble, leaves.” The Brummer Gallery Records. (www.libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll9/id/24175/rec/2).

7. Pitcairn has first loaned the strigilated sarcophagus to the Penn Museum before he loaned it to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The strigilated sarcophagus never came to Bryn Athyn during Pitcairn’s lifetime. On March 11, 1925, Pitcairn received word from G.B. Gordon, director of the University Museum (now Penn Museum), that Penn would accept the loan of objects from Pitcairn (Letter from G.B. Gordon, March 11, 1925. Curatorial Files “University Museum.”). Pitcairn replied the next day that he would have the sarcophagus, as well as a Byzantine door, shipped to Penn directly from New York (Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to G.B. Gordon, March 12, 1925. Curatorial Files “University Museum.”). It seems to have made its way to the Philadelphia Museum of Art from Penn.

8. Letter from Joseph Brummer to Raymond Pitcairn, November 23, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

9. Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Joseph Brummer, November 27, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

10. Letter from Joseph Brummer to Raymond Pitcairn, November 27, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

11. Letter from Joseph Brummer to Raymond Pitcairn, December 5, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

12. Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Joseph Brummer, December 7, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

13. Letter from Joseph Brummer to Raymond Pitcairn, December 11, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers. Appended to the letter is another appeal by Brummer to competition for the piece: “P. S. Mr. Hearst saw the sarcophagus yesterday and it interested him very much.” William Randolph Hearst (1863–1951) was a prominent and wealthy businessman in the newspaper industry who built an enormous collection of a wide range of art, which he installed in his various homes as well as in warehouses.

14. Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Joseph Brummer, December 12, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

15. Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Joseph Brummer, January 31, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

16. Copy of invoice from King-Parker, Inc. to Raymond Pitcairn April 1, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

17. Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Joseph Brummer April 9, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

18. Pitcairn wrote to Bacri Frères: “I have just received a telephone call from the Customs Office, advising me that the glass has been cleared and that I will be able to send for it tomorrow. I will write you as soon as I have examined the glass” (Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Bacri Frères, March 13, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.).

19. Letter from the Secretary to Mr. Pitcairn to O.G. Hamstead & Sons, March 18, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers. Pitcairn received a letter the same day informing him that the packer at the Appraiser Stores “took one board off one of the cases and found contents rattling and put [the] board back on the case again. . .” (Letter from John Gibbons to Raymond Pitcairn, March 18, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.).

20. Letter from Raymond Pitcairn to Bacri Frères, March 19, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

21. “P811: Sarcophagus, marble, leaves.” The Brummer Gallery Records. (www.libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll9/id/24175/rec/2).

22. To date I have not been able to find anything more about the involvement of Toussaint or du Dreneuc with this particular piece. The Brummer Gallery Records indicate that Brummer had an ongoing business relationship with a Toussaint, though the first name Paul is not recorded elsewhere in the records. Raoul Toussaint is recorded as a dealer at the address 33 Rue de Seine, Paris (“Toussaint, Raoul.” Brummer Gallery Records. www.libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll9/id/50210/rec/1). A Toussaint on the Rue de Seine is also listed as a vendor in the “Livre de Police” for the Paris office (“’Livre de Police’ : Blvd. de Raspail, Paris : Feb. 1911–Oct. 1927”, entry 710. Brummer Gallery Records. www.libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll9/id/53683/rec/2). Brummer bought three Egyptian pieces and one Assyrian vase from him on September 26, 1922. Similarly, I have not been able to find any firm additional information about Lelong de Dreneuc. An entry in the “Livre de Police”, however, list a Long-du-Dreneuc from the rue des Beaux Arts who sold Brummer a stone Romanesque capital on December 12, 1913, a decade and a world war earlier (“’Livre de Police’ : Blvd. de Raspail, Paris : Feb. 1911–Oct. 1927”, entry 516. Brummer Gallery Records. www.libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16028coll9/id/53683/rec/2).

23. Letter from Joseph Brummer to Raymond Pitcairn, March 23, 1923. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

24. Letter from Joseph Brummer to Raymond Pitcairn, April 7, 1924. Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers.

25. Lagrèze-Fossat 1872.

26. It is possible that the reference to the 19th century might be a typo for 14th century in the guidebook (“XIX” instead of “XIV”).

27. Ward Perkins 1938, cat. #34; Briesenick 1962, cat. #56; and James 1977, cat. #64. The most recent catalog of this sarcophagus type, published in 2003 also by Briesenick, does not include the sarcophagus from the Château de Massanès (Christern-Briesenick 2003).

28. Lagrèze-Fossat 1872, 354.

29. Lagrèse-Fossat (1872, 357) considers the question of how the sarcophagus made its way into the Château de Massenès and notes that only hypotheses are possible due to the lack of information. He conjectures that it could have been associated with residents of a monastery in the vicinity, but has no evidence for it.

30. In addition to the catalogs in footnote 27, another important study of this material is the proceedings of a conference at the University of Geneva dedicated to this sarcophagus type, which was published in 1993 as the first volume of the journal Antiquité Tardive.

31. The corpus of 262 examples analyzed here is drawn from Christern-Briesenick 2003 and James 1977. An example might be a sarcophagus box, lid, or fragment of either one.

32. For example, Cazes 2006. The iconography likely also had other meanings, for example, evoking the setting of the region’s aristocratic villas, which were decorated with vegetal imagery similar to that found on the sarcophagi (Balmelle 1993).

33. On this area as a late antique cultural zone, see Underwood 2020.

34. See Michel et al. 2019, 19–37.

35. See Cazes 2006 and Cazes and Cazes 2008, 25–28.

36. Young 2001, 178 and 179.

Bibliography

Balmelle, Catherine. 1993. “Le repertoire végétal des mosaïstes du Sud-Ouest de la Gaule et des sculpteurs des sarcophages dits d’Aquitaine.” Antiquité Tardive. Les sarcophages d’Aquitaine. 1: 101–109.

Brennan, Christine E. 2015. “The Brummer Gallery and the Business of Art.” Journal of the History of Collections 27.3: 455–468.

Briesenick, Brigitte. 1962. “Typologie und Chronologie der südwest-gallischen Sarkophage.” Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz 9: 76–182.

Brummer Gallery Records. The Cloisters Library and Archives, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Cazes, Daniel. 2006. “Les sarcophages paléochrétiens sculptés en marbre de Toulouse et la nécropole de Saint-Sernin.” In C. Sapin, ed., Stuc et décors de la fin de l’Antiquité au Moyen Âge (Ve-VIIe siècle) Actes du colloque international tenu à Poitiers du 16 au 19 septembre 2004, 93–101. Turnhout: Brepols Publishers.

Cazes, Quitterie and Daniel Cazes. 2008. Saint-Sernin de Toulouse. Graulhet: Editions Odyssée.

Christern-Briesenick, Brigitte. 2003. Repertorium der christlich-antiken Sarkophage, Vol III: Frankreich Algerien Tunesien. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

Curatorial Files. Glencairn Museum, Bryn Athyn, PA.

Drazin, Adam. 2020. “The Object Biography.” In Lineages and Advancements in Material Culture Studies, eds. Timothy Carroll, Antonia Walford, and Shireen Walton, 61–74. London: Routledge.

Gosden, Chris and Yvonne Marshall. 1999. “The Cultural Biography of Objects” World Archaeology 31.2: 169–178.

Gyllenhaal, Ed. 2017. “Religion at Glencairn Museum: Past, Present, and Future.” In Religion in Museums: Global and Multidisciplinary Perspectives, eds. Gretchen Buggeln, Crispin Pane, and Brent Plate, 239–236. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Gyllenhaal, Ed. 2022. “Why Did Raymond Pitcairn Build Glencairn? From Cloister Studio to Castle.” Glencairn Museum News 1, Feb. 23, 2022. (www.glencairnmuseum.org/newsletter/2022/2/22/why-did-raymond-pitcairn-build-glencairn-from-cloister-studio-to-castle)

Hinton, Jack. 2017. “Reflected Glories: Raymond Pitcairn’s Loans to the Philadelphia Museum of Art.” Glencairn Museum News 8, Aug. 24, 2017. (www.glencairnmuseum.org/newsletter/2017/8/22/reflected-glories-raymond-pitcairns-loans-to-the-philadelphia-museum-of-art)

James, Edward. 1977. The Merovingian Archaeology of South-West Gaul. Part ii: Catalogues and Bibliography, Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

Joy, Jody. 2009. “Reinvigorating Object Biography: Reproducing the Drama of Object Lives.” World Archaeology 41.4: 540–556.

Kopytoff, Igor. 1986. “The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process.” In The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. Arjun Appadurai, 64–91. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lagrèze-Fossat, A. 1872. “Le Sarcophage de Massanés.” Bulletin archéologique et historique de la Société archéologique de Tarn-et-Garonne, 2: 353–357.

Michel, Anne, et al. 2017. Saint-Seurin de Bordeaux, un site, une basilique, une histoire. Pessac: Ausonius Éditions.

Raymond and Mildred Pitcairn Papers. Bryn Athyn Historic District Archives. Glencairn Museum. Bryn Athyn, PA.

Underwood, Douglas. 2020. “Good Neighbors and Good Walls: Urban Development and Trade Networks in Late Antique South Gaul.” In Urban Interactions: Communication and Competition in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages, Michael J. Kelly and Michael Burrows, eds., 373–427. Binghamton, NY: Punctum Books.

Ward Perkins, J.B. 1938. “The Sculpture of Visigothic France.” Archaeologia 87: 79–128.

Young, Bailey. 2001. “Sacred Topography: The Impact of the Funerary Basilica in Late Antique Gaul.” In Society and Culture in Late Antique Gaul: Revisiting the Sources, Ralph W. Mathiesen and Danuta Shanzer, eds. 169–182. London: Routledge.