Glencairn Museum News | Number 4, 2014

The Venerable Lama Losang Samten Creating a Sand Mandala at Glencairn Museum

Where were you born, and when did you begin serving the 14th Dalai Lama?

I was born in Tibet in 1953, and in 1969 I began to serve as a personal attendant to His Holiness the Dalai Lama in India.

Where did you learn how to make mandalas, and how long have you been making them?

I learned how to make mandalas at the Namgyal Monastery in India, the personal monastery of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Namgyal has been the monastery of the Dalai Lamas since the second Dalai Lama, so it has a three- or four-hundred-year history. Making mandalas is a part of our training at the monastery, and during the time I was learning how to make mandalas—the late 1960s and early 1970s—there were twenty eight of us learning together.

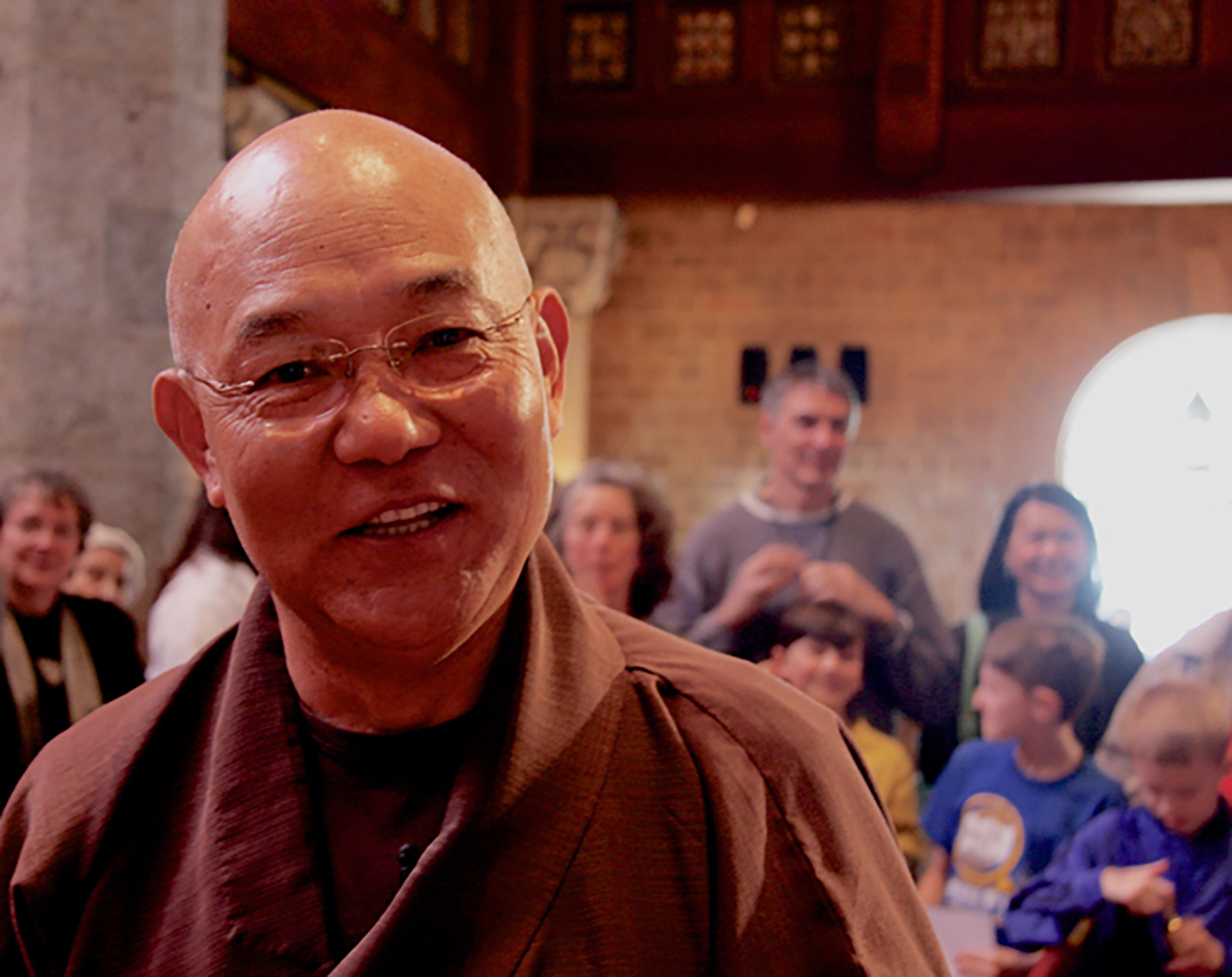

Figure 1: Ven. Losang Samten

Why did you come to the United States in 1988?

I traveled from India in 1988 to create the first public sand mandala in the West. This was in New York City, at the American Museum of Natural History.

How many people in the world make authentic Tibetan sand mandalas?

Not many people make authentic sand mandalas such as the Amitabha [being made at Glencairn this week] and the Kalachakra and other authentic designs. There are probably less than one hundred truly qualified artists. Many mandalas are made for the tourist market, especially in Nepal, but they are usually not authentic, and this can be seen from the fact that the colors are often wrong or the design is not quite right.

Figure 2: Amitabha Mandala

How long does it take make a mandala?

The time it takes to complete a mandala depends on the design and the size. The bigger the size of the mandala the more time is required to complete it. A mandala that is about six feet in size will likely take three or four weeks to complete.

How do you prepare to make a mandala, both physically and spiritually? Is everything planned out in advance, or do you make changes as you go?

In a way everything is fluid, but I try not to change the basic image. I want to present mandalas that are as authentic as possible, wherever I go, and I rely on what I was taught by my teacher at the monastery. One of the biggest aspects of the preparation is the process of making the different colors of sand. This is very time consuming. Also, every day that I am working on a mandala, I prepare ahead of time with prayer and meditation. I do this either at my home or the place where the mandala is being created.

Figure 3: Ven. Losang Samten with Sand for Mandala

What are some of the different kinds of mandalas?

There are numerous kinds of mandalas. Since I began making mandalas in the West in 1988, there are certain designs I have routinely been making: the Kalachakra Mandala, or the Wheel of Time, the Mandala of Compassion, the Mandala of Wisdom, and the Wheel of Life Mandala.

Why do you choose a particular mandala design at a particular time and for a particular place? Why did you choose the Mandala Amitabha for Glencairn this week?

This week I chose the Amitabha Mandala for several reasons. Each year I have had the wonderful opportunity to display a mandala in this beautiful building at Glencairn. So each year I try to present a new and different mandala. The Amitabha Mandala is helpful for the constantly changing journey of life that every human being is on. The Amitabha Mandala is supposed to increase wisdom, helps overcome death, and has special power or blessing for rebirth. So I thought this would be good for all of us.

Figure 4: Amitabha Mandala

Exactly what will happen to the mandala at Glencairn after it is completed?

After completion of the mandala at Glencairn we always have a dismantling ceremony, which we are also going to do this year. The dismantling includes everything, the designs and colors. The ceremony starts with me, and then I like people to participate in pushing the sand into the middle of the table to mix all of the colors together. The sand is then dispersed in water [a pond on the grounds of Glencairn]. Plus, if people want, they can take a little bit of sand from that day and disperse it around their home, or in their garden. It is very beneficial.

Figure 5: Dismantling of the Mandala

What is the significance of pouring the mandala sand into the water after it has been dismantled?

Water is such an important element in our lives; if you look at the human body, the greatest portion is made up of water. Clean water is something that is so important on earth, and sand is actually created by water action, so when we return it to the water we are completing a circle. That is why a body of water is important in this case.

Figure 6: Pouring the Mandala Sand into a Pond near Glencairn

What do you think about mandalas that people pay to have permanently preserved rather than ritually dismantled? What do you think about that practice?

I have no problem with that practice, no problem at all. If a sand mandala is being made for a religious occasion or religious ceremony, then it will very likely have to be dismantled. But very often the mandalas I am making, in museums and other places, are for the purpose of education and cultural sharing. If in these situations people would like to preserve them, I am fine with that.

Do you see similarities between the different religions in the world, such as Buddhism, Christianity, and Judaism?

Very much so, they are very similar, and this is such a wonderful thing. When I first came to the United States in 1988, of course, the sand mandala I displayed was my main purpose. But personally, in my heart, another reason for coming was my desire to truly learn more about Christianity and Judaism. The more I learn, the more I see similarities, and this is such a wonderful thing.

Tell us about the altar you set up in Glencairn’s Great Hall. Why have you made the altar, and how will it be used?

In a way, the mandala and setting up the altar is to educate people. To me personally, going to a church, or a synagogue, or any other spiritual place, gives me such an uplifting feeling. And so by setting up the mandala, plus setting up the altar, people who come will be taught about the tradition of Buddhism, especially in Tibet. They will learn what altars look like, what they represent, how they are used, and what is their purpose; and this is such a wonderful education. So I am very happy we are setting up the altar this year.

Figure 7: Tibetan Buddhist Altar in Glencairn Museum

What is the significance of the prayer wheels?

The prayer wheels have so many stories surrounding them, but I don’t want to get too detailed. Inside the prayer wheels there are many different prayers; for example, the prayer of compassion, the prayer of all living beings wishing to live in peace, overcome suffering . . . so many prayers are written on the paper. When we turn the prayer wheel clockwise, we truly believe the energy rises all over the world and is beneficial.

Figure 8: Buddhist Prayer Wheel on Altar

What is the significance of bells in Buddhist practice?

Bells have many different meanings. In the first place bells symbolize wisdom. The bell is for calling the gods and goddesses to ask them to hear our prayer. The bell is a symbol of wisdom and interdependence. What I mean by interdependence is that even though we are each an individual, it is so important to know we all are connected with each other. Not only are we connected to the earth, and air and space, but we, every living being, have a connection with each other. So ringing the bell is a reminder for us, that yes, we are connected; we are one.

Figure 9: Bell on Altar

Can you tell us about the auspicious symbols in the cloth paintings on the altar?

There are eight auspicious symbols. The first one is an umbrella, symbolizing protection. We all need protection—inner protection, outer protection, protection. So the first one is an umbrella, and the second is two golden fishes, which symbolize harmony. The third one is a vase—knowledge is so important. The fourth one is the lotus, symbolizing kindness, love, caring, compassion. The fifth is a conch shell symbolizing sharing; when the conch shell is blown, everybody hears the sound. When we receive knowledge we should not keep it to ourselves, we should share it with other living beings. The next symbol after the conch shell is endless knots. It symbolizes long life, longevity, life that never ends. So, it is the wish that everybody have good health, and live longer, not only physically, but also mentally. Also it is about relationships—between parents and kids, teachers and students, the positive relationships that lead to a long life. So number seven is a victory banner, a cloth banner. In Tibet they can also be made out of clay or gold and silver. They are hung on the corner of temples or houses, and symbolize wealth. In order to share loving kindness and compassion with others, we need wealth. Wealth is important not only for individuals, but for the world. And the last one, number eight, is the dharma wheel, which is a symbol of direction—the right direction, the right path. So, just like in a car, the person holding the wheel determines the direction. So those are the eight auspicious symbols.

Figure 10: Cloth Painting with Auspicious Symbols on Altar

The story behind them is that when Buddha was born in India, 2,600 years ago, in his town, Kapilavastu, everybody saw those eight auspicious images in the sky, cloud images. So at that time the yogis, Hindu yogis, looked at the sky and said, “these are the eight auspicious symbols, a remarkable human being must have been born on the earth.” I’m sure that happened to Jesus too. So ever since they have been called the eight auspicious symbols.

What is the significance of beads in Buddhist practice?

The beads, in Buddhist and Hindu tradition, are for counting mantras to the gods and goddesses. In Buddhist tradition there are many different mantras: for example, the mantra of compassion, the mantra of wisdom, and the mantra of healing. When people go to a retreat or other religious setting, they need to count the number of mantras. The mantra sounds like this [repetitive words in Tibetan], so that way you know how many you have said by counting the mala beads as you go. The mala beads are also a physical reminder of spiritual practice.

Figure 11: Beads on Altar

Can you talk about the offering of water that you change daily at the altar in Glencairn’s Great Hall?

At the altar, each morning, I offer either water or a small cup of coffee or a small cup of tea. At the end of the day the offering is removed, and the bowls are cleaned and refilled the next day. For every bowl that I am putting water in, I am meditating or thinking about what each water bowl represents. They do not just represent water, and each one represents something different. The first water bowl invites the invocation; the second one represents a flower; the third one incense; the fourth, light; the fifth, perfume; the sixth one, fruit; and the seventh one, music. So that is one way of interpreting the seven water bowls. But there are many other possible meanings, so when I am putting the water on the altar, I am thinking about the quality I am presenting on the altar. So, in Buddhist belief, setting up the altar and offering the water is part of accumulating merit. The more you clean a church or temple or synagogue, the more it really purifies you, so that is one of the spiritual practices of Buddhism. It creates good karma.

Figure 12: Ven. Losang Samten Offering Water at the Altar

You don’t seem to proselytize about your beliefs, or try to convince people to become Buddhists. Is this a conscious decision for you and other Buddhists?

That is a common Buddhist concept. Not only for me, but in a way, everybody who is a Buddhist must follow this practice. Buddha taught that if you are following my teachings, you cannot promote your beliefs to somebody else. Everyone must make their own choices, so promoting or proselytizing is not really a Buddhist belief in the first place. I think this is a very good idea. And the second reason I follow this practice is because even I, myself, don’t know if I am Buddhist or non-Buddhist—I really don’t know. I do know I truly practice Buddhism, yet I also have respect and love—deep respect—for other faiths, and tremendous devotion to the life of Jesus. I am so happy to have been living these many years in the United States, meeting lots of Christian monks and Christian nuns—Benedictine, Franciscan—and it has been wonderful. For example, St. Francis of Assisi, to me, when I read about his story, his life story, is such a good example of a Buddhist monk, and he doesn’t seem any different to me than a good Buddhist monk. So, generally speaking, in the world, in the past, if somebody knew all other religions well, they would not see conflicts. We tend to have a problem if we don’t really know another religion well, if we only know it superficially, and miss the true message of that religion.

Figure 13: Ven. Losang Samten Meeting with Visitors

For a number of years now, certain museums have had relationships with Buddhist monks who make sand mandalas. How do you feel about collaborating in these spaces?

I think it is a positive thing, oh yes, it is very positive. Personally, I am now 61 going on 62, and yesterday I met and talked to a gentleman, living in this area, who is 66. He told me he is retired, and came today to see the mandala. I asked him what he does, and he said nothing in particular because he is retired. So when I meet people who are close to my age I think, okay, I don’t know how soon, but yes it is good to eventually retire and not make many mandalas. I am in the process of thinking about that, and yet I very much enjoy making mandalas. Making mandalas gives me the opportunity to meet so many different types of people, the opportunity to listen to their life stories and answer their questions. So I am not making mandalas for financial reasons, or other reasons, but because I enjoy it and I enjoy meeting people and listening to their stories and sharing with them. That is such a wonderful opportunity for me. I enjoy it very much.

Figure 14: Ven. Losang Samten Meeting with Visitors

So you are thinking about retiring, but not yet?

Yes, but compared to many years ago I accept fewer invitations, and I am making mandalas at places I already have a connection with. I am keeping that as my routine.

(Interviewed by CEG/KHG/PC)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.