Glencairn Museum News | Number 3, 2014

Thirteenth-Century Bronze Bell on East Side of Glencairn's Great Hall

Figure 1: Thirteenth-Century Bronze Bell on West Side of Glencairn's Great Hall

On November 11, 1965, Raymond Pitcairn gave a tour of Glencairn to James J. Rorimer, director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rorimer, formerly a curator of medieval art at the Met, had also served in World War II as head of the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section of the Seventh United States Army (aka the “Monuments Men”). This historic tour was recorded on audiotape, a transcript of which survives in the Glencairn Museum Archives. While they were in the Great Hall, Pitcairn pointed out two bronze bells hanging from ropes above the second-floor balcony, and told Rorimer the story of how he had acquired them. He had first encountered the bells in the New York City gallery of Dikran and Kevork Kelekian, antiquities dealers who supplied objects to some of the most prominent museums and collectors in America. According to Pitcairn,

“Kelekian brought those over [from Europe], and I went to his place one day and I thought I would like to have those bells. He wanted a pretty good price for them. I let it go, and went back some months later. ‘How about those bells?’ He said, ‘I sold them to William Randolph Hearst.’ When Hearst made his sale—with Gimbels, I think—I said to the people there that I had seen these things that were on sale, but that I didn’t see the two bells. ‘We will put them in the sale if you would like to make a bid for them.’ My wife said she would give them to me as a birthday present. They really have some very nice inscriptions on them.”

The events described by Pitcairn took place over at least a twelve-year period. It is not known when he first saw the bells in the Kelekians’ New York gallery, but in 1926, two years before construction began on Glencairn, Pitcairn wrote the following to Dikran Kelekian:

“Sometime ago your brother [Kevork] offered me two old bronze bells. Before I had an opportunity to purchase them they were sold to Mr. Hearst. Miss Kelekian will recall the circumstances.

In connection with the little castle which I contemplate building for my collection I should much like to have these bells and it occurs to me that you might be in a position to obtain them from him.

My suggestion is that sometime when Mr. Hearst is making a purchase you could mention the matter to him without disclosing my name, merely informing him that a good client had been offered these bells which were sold by your brother to Mr. Hearst, and that possibly he would be willing to trade them in on the sale of something he desired in the future, at a reasonable advance over their cost to him, provided he had no definite use for the bells. If some such arrangement could be arrived at, I should much appreciate your securing them for me.”

Kelekian wrote back immediately, telling Pitcairn, “I shall take pleasure in speaking to Mr. Hearst, at the first opportunity, about the bells . . . When I see him I shall approach the subject discretely.” To date, however, no documentation has been found to indicate whether Kelekian ever approached Hearst on the subject.

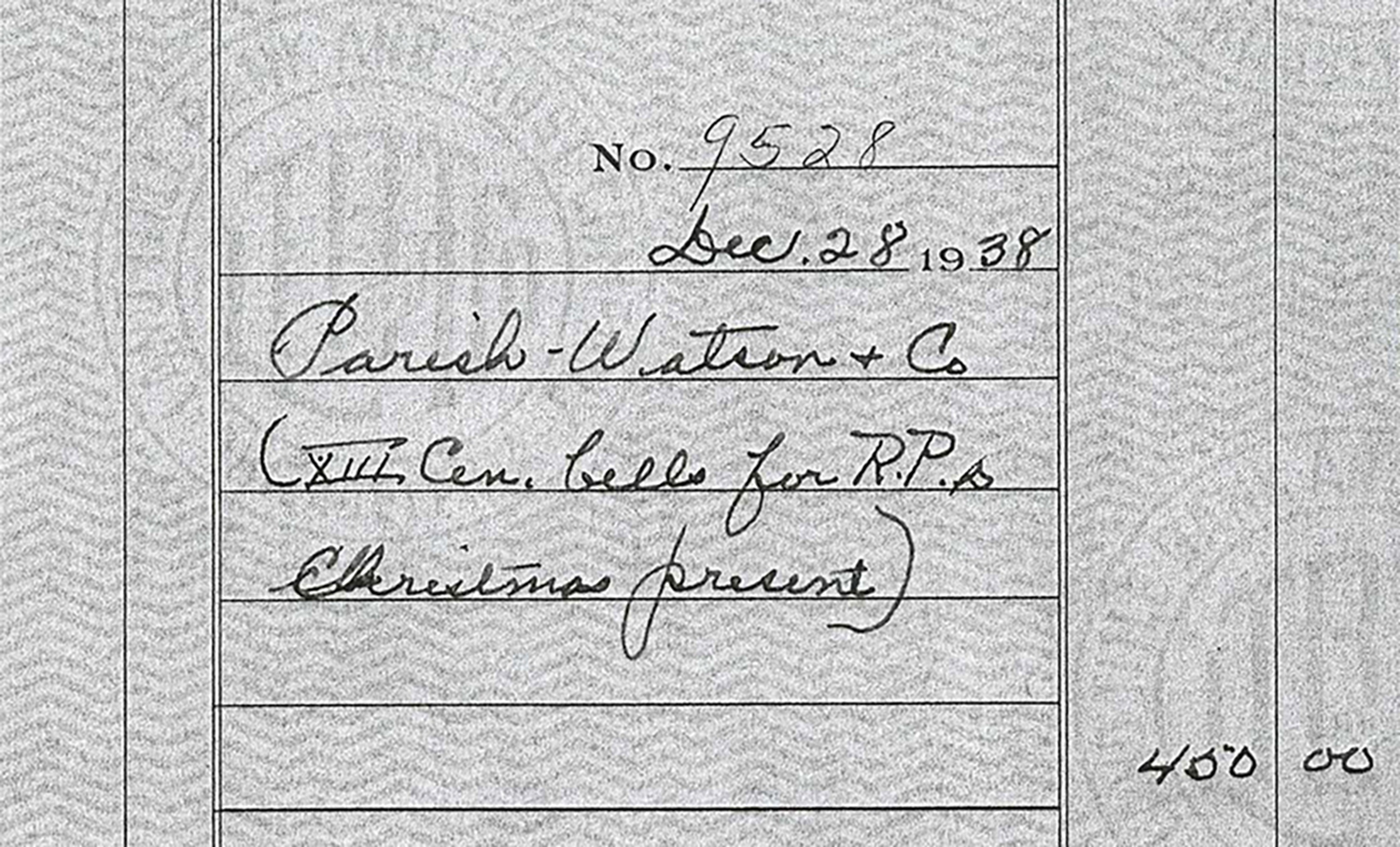

Figure 2: Mildred Pitcairn Check Stub for Purchase of Bells

It was not until December, 1938—twelve years after Pitcairn had written to Kelekian about the bells—that Mildred, Raymond’s wife, wrote a check (#9528) for $450 to Parish-Watson & Co., another New York City dealer. The stub in her personal checkbook reads as follows: “XIII Cen. Bells for R.P.s Christmas present.” In the late 1930s, half of William Randolph Hearst’s art collection was being sold to compensate for corporate financial losses incurred during the Great Depression. In 1938, the year Mildred wrote the check, Macdermid Parish-Watson’s company was hired to conduct the sale of a portion of the collection. The initial sales were conducted privately, but in mid-November a sale was opened to the public. A five-story warehouse was leased for the purpose of displaying the items. It seems likely that Raymond Pitcairn mentioned his interest in the bells to the Parish-Watson company at this time, and arranged to make a bid if they would enter them into the sale (see the above transcript of his conversation with James Rorimer).

As for Pitcairn’s 1965 remark to Rorimer that Hearst’s sale of the bells was “with Gimbels, I think,” it seems likely that he had confused the Parish-Watson sale with a later sale of Hearst material conducted at Gimbel Brothers Department Store in New York City. In the early 1940s, Gimbels signed a contract to sell a large portion of the Hearst collection; in fact, at one point the entire fifth floor was devoted to the sale. These public sales captured the popular imagination. A New Yorker cartoon published on April 12, 1941, pictured a man in a bowler hat and his wife, wearing a fur coat, surrounded by paintings and suits of armor. The man says to his wife, “If you’re so hell-bent on buying something that belongs to Mr. Hearst, you can get a Journal-American [newspaper] for three cents.”

Figure 3: Inscription on 1297 Bell on East Side of Great Hall

During the tour of Glencairn, James Rorimer, seeing the bells at a distance from below, guessed that they dated to the 16th or 17th centuries. Pitcairn replied, “No, I think they are supposed to be 13th Century.” Many years later, when Glencairn became a museum and Pitcairn’s collections were catalogued, the bells were listed as dating to the 15th Century (for reasons unknown). As for Pitcairn’s comment during the tour that “[the bells] really have some very nice inscriptions on them,” this information never made it into the museum catalogue—perhaps because the bells were never examined up close. Last summer Ed Gyllenhaal, Glencairn’s curator, after rereading the tour transcript, photographed portions of an inscription on the larger bell from the ground with a telephoto lens. In February of this year, Gyllenhaal and Drew Nehlig, historic buildings project manager for the Bryn Athyn Historic District, photographed both bells close up from the top of a ladder. Only one of the bells contains an inscription—the larger one, located on the east side of the Great Hall. It reads as follows: A D MCCLXXXXVII. The Latin abbreviation and Roman numerals stand for “Anno Domini 1297,” i.e. “In the year of the Lord 1297.” Both bells still have old (dealer?) tags that read, “Church Bell 13th Century.”

Several weeks ago, Glencairn Museum invited Dr. Steven Ball (Doctor of Musical Arts), an expert in campanology—the study of the science of bells—to examine our 13th-century bells. He has generously agreed to answer some questions for Glencairn Museum News.

Exactly what is the study of campanology?

The profile of the bell is what determines the harmonic structure, therefore the tuning. The way a bell sounds (whether or not it is musical, even!) is a matter of both the profile and the casting technique used to create it. It is the combination of these two things which is the basis of the study of campanology, as well as all of the applied arts of bell ringing, the study of the historical and cultural significance of bell ringing, and the bells and associated hardware itself.

Based on your examination, what are your general impressions of Glencairn's 13th-century bells?

They are remarkable survivors from the period, not just in that they are both bells of extreme antiquity, but also that (based on the details of the molding) they seem quite possibly related to each other in being cast by the same bell founder. What makes them rare survivors may be of some interest to your readers, who may not be otherwise acquainted with the world of bells.

Figure 4: Profile of Bell on West Side of Great Hall

The modern bell shape, or “profile,” is an evolved form. The shape of a bell has been in an almost constant state of evolution, even into modern times. This is due especially (in Western Europe) to the development of the technical abilities of the founders to cast increasingly large amounts of metal, and with greater precision, as well as an attempt to rectify deficiencies in design. As one moves backwards from modern times into the Renaissance (when bell tuning was invented), into the high Gothic and even earlier, the sound bow (thickening at the lip of the bell) disappears and the bells begin to take a more primitive dome (or “beehive” or “sugar-loaf” shape). Glencairn’s bells come from a moment early in the evolution of the Gothic bell profile when sound-bow was just beginning to be added to the basic inverted cup-shape with sloping sides. The sound-bow is important, not only to strengthen the bell from shattering against the blows of the clapper (thus necessitating re-casting which is why many of these bells have not survived), but also increasing the reverberation time of the lower partials. In this case, the sound bow can be seen quite clearly as the external ring added around the perimeter of the lip of the bells.

Figure 5: Examining Glencairn's Thirteenth-Century Bells

Bells in antiquity were among the most valuable objects of their time, as in the pre-industrial world large accumulations of metal were difficult and extremely expensive to produce. For this reason, when bells cracked they were most frequently broken up for new castings immediately. As objects of great value, they were also the first things to be confiscated during war, and with the introduction of cannon and gunpowder in Europe (possibly as early as the 11th or 12th century), they were not infrequently converted by the same founders during times of war into guns themselves. Thus, the old saying that the bells were the “cannons of the church”—heavy spiritual artillery with a sort of understood second meaning for those who heard the phrase. It is for these reasons, really, that survivors from this period are extremely rare.

So these two bells likely belong together, as part of a set or group?

Yes, it appears possible. This is based especially on the similarity of the shape of the “cannons” or cast bronze rings from which the bells are suspended. When the bells were made, these were formed from wax. If the cannons of both bells were the product of the same wax mold (difficult to discern under the current display conditions), then the bells are almost certainly from the same bell founder. They appear to be almost identical, thus the supposition that they are possibly the work of the same foundry.

What country do the bells likely come from, and how can you tell?

The bells are almost certainly Italian, something which can be discerned by the very narrow shoulder.

What is their likely context, sacred or secular?

Figure 6: Inscription Band on Bell on East Side of Great Hall

If the bells were used as a pair (whether or not by the same bell founder) and housed in a tower together, they were almost certainly performing an ecclesiastical function. This seems likely, as a cross appears as the only ornament (other than the inscription of the date of 1297) on the larger bell. According to the custom of the Roman Catholic Church, and as specified in books regarding liturgical practice, a pair of bells would normally have been used in a religious house such as a monastery or convent (larger and smaller for the differentiation between the major and minor canonical hours), although it is possible that there were other bells associated with these two originally. A single bell would be normal for an oratory, a parish church would usually have at least three, and a cathedral church at least five. With these combinations of bells, a language could be developed to articulate the progressive degrees of solemnity of the church calendar.

It is a serious and most unfortunate mistake in modern times (usually due to automation) that all of the bells in a tower are sounded every time the bells are rung, as it completely destroys the magnificent and complex voice and language of signals which each individual tower can have. It is also a beautiful thought to know that when a bell sounds, someone is at the other end of the rope calling people to that place.

Why might these bells have appeared on the antiquities market? (Perhaps because they are cracked?)

Yes, this is almost certainly the case. With the smaller bell, it is also apparent that the iron staple which suspended the clapper rotted away and, even possibly as recently as the 19th century, a new staple was fitted which suggests that the bell was in active service until modern times.

How rare is it to find bells of this age in this country?

Extremely! For the reasons mentioned above, bells of this era are most unusual.

Figure 7: Thirteenth-Century Bronze Bell on East Side of Glencairn's Great Hall

In particular, what makes these bells of special interest is that they are almost exactly contemporary with one of the earliest sources on bell founding in Western Europe, those found in a manuscript which is a compilation of documents in three sections attributed to Theophilus Presbyter (c. 1070–1125) called De Diversis Artibus (“On Various Arts”), and which is, indeed, the very same source upon which was focused much of the early research regarding stained glass formulae used to make windows for Bryn Athyn Cathedral early in the 20th century. A slightly later, but still important contemporary piece of documentation often compared with this source is the 14th-century “Bell Founders Window” of York Minster (in York, England), the existence of which, again, points to the singular importance of the Glencairn bells as extremely rare surviving examples from this period of bell casting.

(CEG/KHG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.