Glencairn Museum News | Number 8, 2014

Fonthill (1908-1912), the home of Henry Chapman Mercer. Photograph by Ed Gyllenhaal.

Henry Chapman Mercer (1856-1930) was nearing the end of his life when Raymond Pitcairn (1885-1966) was just beginning construction on Glencairn, his castle-like home in Bryn Athyn, Montgomery County. Fonthill, Mercer’s own castle-like home in Doylestown, Bucks County, bears little resemblance to Glencairn in terms of architectural style. Nevertheless, these two men, who built castles in adjoining Pennsylvania counties, shared similar backgrounds, interests, and ambitions.

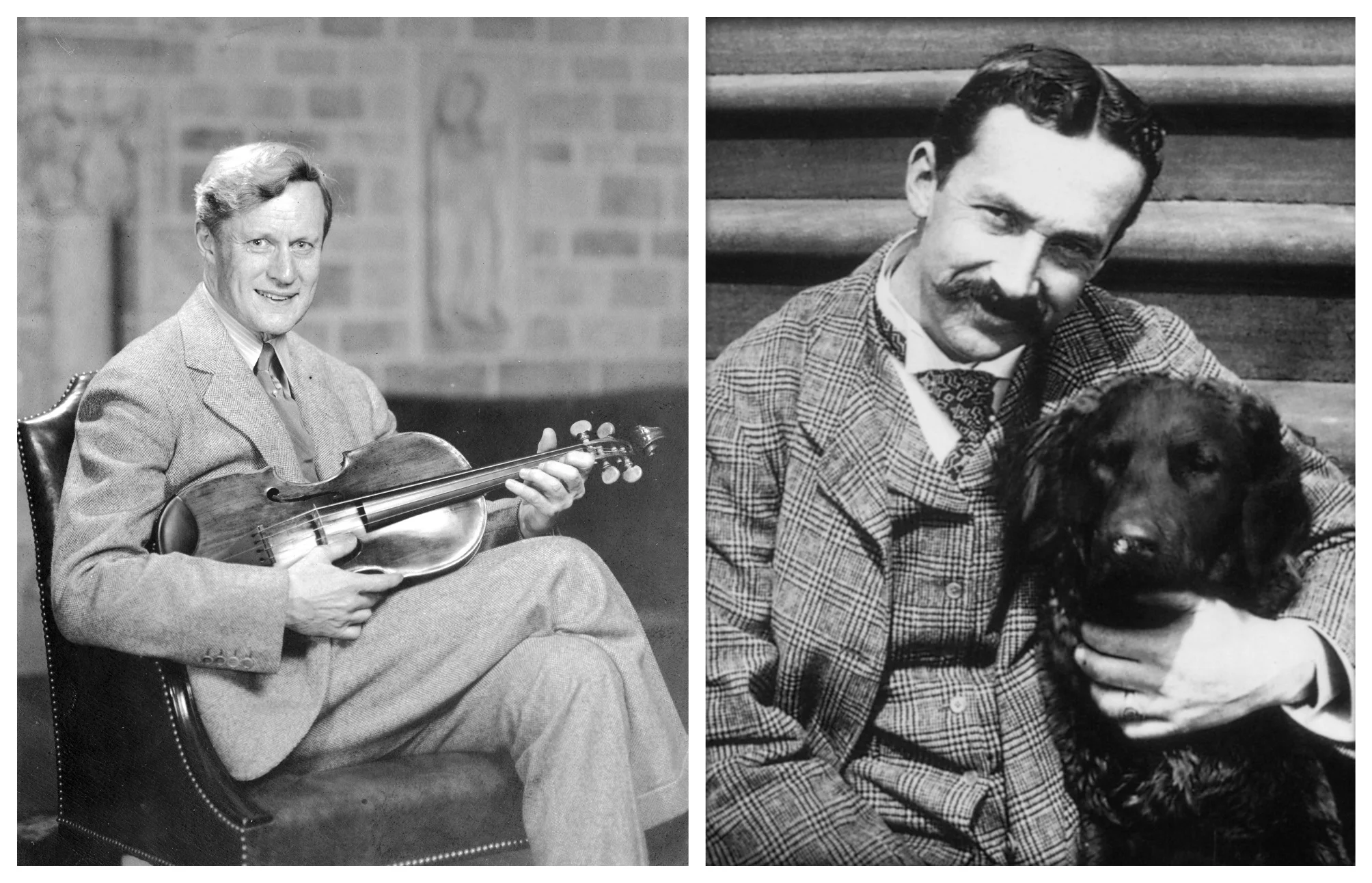

Figure 1: Raymond Pitcairn (left) seated in the Great Hall of Glencairn with his viola; Henry Chapman Mercer with his beloved dog, Rollo.

Both Mercer and Pitcairn came from well-to-do families who provided them with an excellent education, the luxury of travel abroad (and exposure to the art and architecture of Europe), and the financial means to pursue their individual passions. Both men attended the University of Pennsylvania Law School, but subsequently left the profession to pursue their interests in architecture, collecting, and the revival of the production of bygone crafts. The philosophy of the Arts and Crafts Movement interested both Mercer and Pitcairn—although they distanced themselves from the socialism espoused by some leaders of the movement.

Figure 2: Ancient pottery from Mercer's collection displayed in his study at Fonthill. Photograph by Jack Carnell.

Raymond Pitcairn supervised the construction of Bryn Athyn Cathedral, dedicated in 1919, and later Glencairn, the home he built for his family from 1928 to 1939. To this end he established the Bryn Athyn Studios, with on-site workshops for stained glass, mosaic, woodwork, metalwork, and stonework. Like Mercer, Pitcairn loved medieval art, and believed that “paper architecture,” with its straight lines, T-squares and triangles, had led to a decline in craftsmanship in the modern era. Pitcairn, who desired to build “in the Gothic way,” believed that “artistic guidance applied continuously, and designers and craftsmen who work side by side, see eye to eye, and strive ever to build better and to produce work more beautiful, are needed for real building” (Raymond Pitcairn,“Bryn Athyn Church: The Manner of the Building and a Defence Thereof.” Book draft, Glencairn Museum Archives, p. 16).

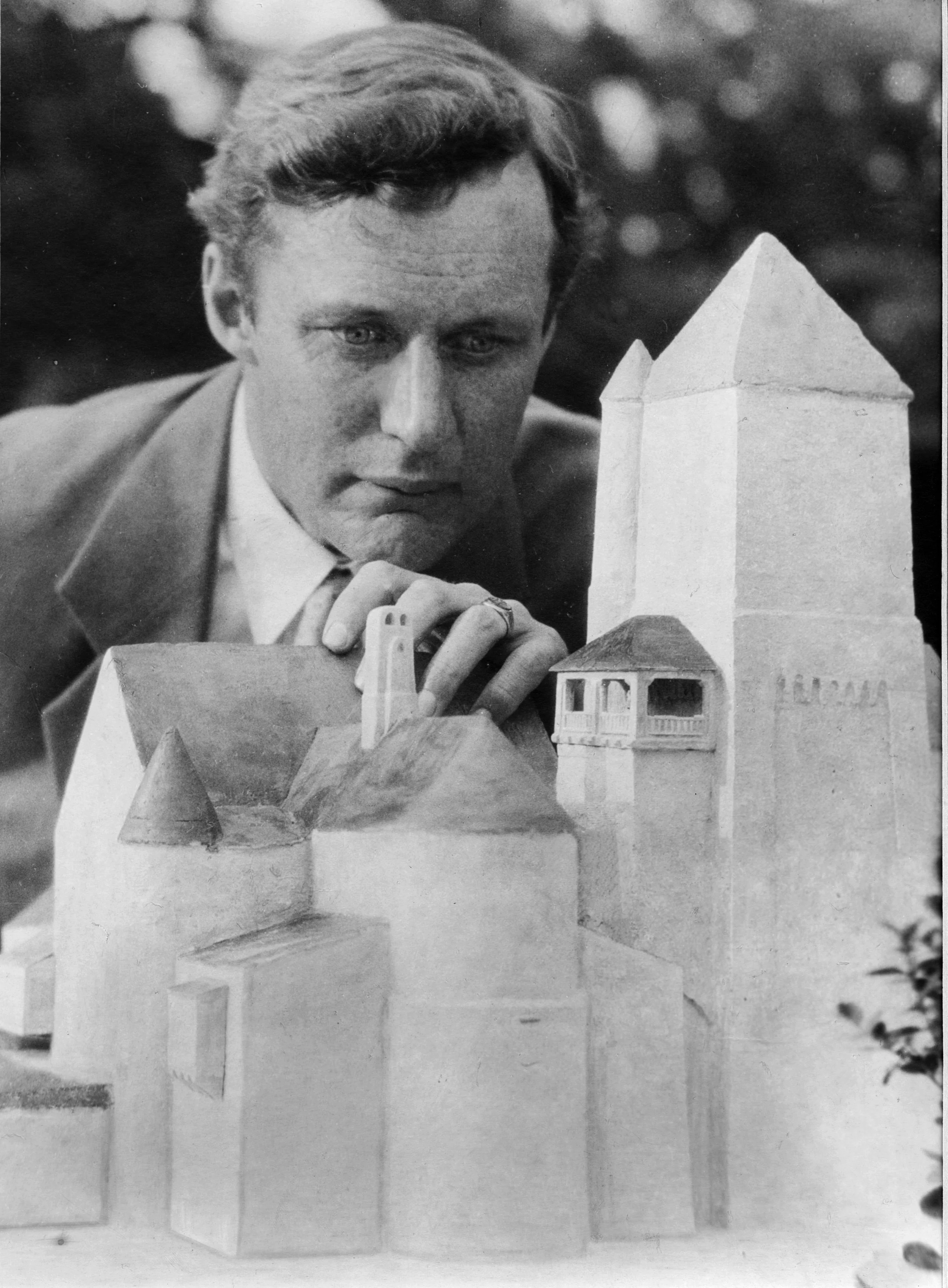

Figure 3: Raymond Pitcairn with an architectural model of Glencairn.

The greatest achievement of the Bryn Athyn Studios was the revival of the medieval method of making pot-metal stained glass. Pitcairn’s glassworks produced stained glass windows for both Bryn Athyn Cathedral and Glencairn. During the early years of this undertaking, countless experiments took place in order to perfect the recipes for the various colors of glass. The construction of the cathedral, a Gothic and Romanesque complex, was the original motivation behind Pitcairn’s art collection. He began by purchasing medieval stained glass and sculpture—primarily thirteenth-century pieces from France—in order to inspire his craftsmen. Eventually he went on to collect art from ancient Egypt, the ancient Near East, ancient Greece and Rome, and a few objects from Asian and Islamic cultures. The size of his art collection, and his desire for a suitable building in which to display it, played an important role in his decision to build Glencairn, his Romanesque-style home. Pitcairn incorporated many of his medieval pieces directly into the fabric of the building.

Figure 4: Mercer Museum in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Photograph by Ed Gyllenhaal.

Henry Mercer built the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works, Fonthill (his private residence), and the Mercer Museum (Figure 4). Like Pitcairn, he collected extensively, but the focus of Mercer’s collection was tiles, tools, and artifacts of pre-industrial life. Mercer’s desire for a suitable building in which to display his personal collection influenced his decision to build Fonthill; like Pitcairn, he used many of these objects to decorate his home (Figure 2).

Figure 5: The library at Fonthill, decorated with tiles made in the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works. Photograph by Jack Carnell.

The ceramic tiles that decorate the walls, floors, ceilings, fireplaces, and stair risers—in fact, nearly every conceivable surface—of Fonthill include both examples from his personal collection and those made in his own Moravian Pottery and Tile Works. Saddened by the loss of the Pennsylvania German potteries during the late 19th century, Mercer had founded the Tile Works in 1898 as a way to revive this dying ceramic tradition. (Because traditional Pennsylvania German tableware had been superseded by modern china, he decided to focus on tile making.) Mercer experimented with a variety of slips and glazes in order to vary the finish of each of his tiles, just as Pitcairn would later conduct studies and experiments to revive the lost art of medieval pot-metal stained glass. Some of Mercer’s tiles were inspired by medieval designs he had seen from England, Ireland, and Germany. He supervised the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works from the time it was built in 1898 until his death in 1930. The Tile Works, now owned by the Bucks County Department of Parks and Recreation, continues to produce Mercer’s designs for sale today, and is open to the public for self-guided tours.

Figure 6: Rollo's stairs in Fonthill. Photograph by Jack Carnell.

Mottoes, phrases, and quotations in Latin and English can be found throughout both Fonthill and Glencairn. At Fonthill these inscriptions are usually spelled out using ceramic alphabet tiles produced in the Tile Works, whereas at Glencairn they are incorporated into stained glass windows or glass mosaics, engraved on teakwood beams, or carved in stone. Inscriptions in Fonthill are often cryptic, but reveal Mercer’s interest in history and philosophy. There are also touches of humor, such as the tribute he paid to his beloved dog, Rollo (Figure 1). When the stairs were being built leading up from the Columbus Room (one of 32 stairways in Fonthill), the dog’s paws were pressed into the cement, and the words “Rollo’s Stairs” were added to the stair risers (Figure 6). Paw prints can also be seen at the Mercer Museum, and after Rollo’s death in 1916 Mercer wrote, “May his footsteps outlast many generations of men on his stairways at Fonthill and the Bucks County Historical Society” (“Tribute to Rollo: From a Notebook of Henry Chapman Mercer,” Penny Lots Vol. 26, No. 2, 2012, 16). Pitcairn’s inscriptions at Glencairn are generally taken from the Bible or the theological works of Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772). Engraved in gold lettering on two teakwood beams in the entrance hall of Glencairn is this inscription (Figure 7): “That a house may be built, materials must first be provided, the foundation laid, and the walls erected; and so finally it is inhabited. The good of a house is the dwelling in it” (Emanuel Swedenborg, The Doctrine of Charity, 1766, ¶129).

Figure 7: Inscription on a teak beam in Glencairn's entryway.

Although Mercer and Pitcairn lacked formal architectural training, this did not discourage them from pursuing their unique architectural visions. Both men maintained complete control over the finished product by using three-dimensional models to further the design process (Figure 3). While their homes could be seen as monuments to bygone eras, Mercer and Pitcairn were attempting to build structures in which they could actually live—filled with modern amenities such as the latest in electrical lighting, plumbing, and central heating. Fonthill and Glencairn were homes that, in Mercer’s words, “combined the poetry of the past with the convenience of the present” (W. T. Taylor: “Personal Architecture: The Evolution of an Idea in the House of H. C. Mercer, Esq., Doylestown, Pa.,” The Architectural Record 33, March 1913, 242-254).

Figure 8: The "Yellow Room," a guest room in Fonthill. Photograph by Jack Carnell.

(CEG/KHG)

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.