Glencairn Museum News | Number 9, 2014

Faience statuette of Taweret (12cm) and faience amulets of Taweret (smallest = 2cm) in Glencairn Museum’s Egyptian collection.

The family unit was an important feature of ancient Egyptian life, both for humans and for the divine. In temples throughout Egypt, gods and goddesses formed family groups consisting of a father, mother and child god. The best-known example of one of these divine families is that of Osiris, Isis and Horus. In addition to being an extremely powerful goddess, Isis performed the role of the model wife and mother (Figure 1). After Osiris’s death at the hand of his brother Seth, she took great care to protect her son from his uncle to ensure that Horus would take his father’s throne as his rightful heir.

Figure 1: Bronze statuette of the goddess Isis nursing the infant Horus. Late Period (664-332 BCE). University of Pennsylvania Museum E12548.

Establishing a household and producing a child—particularly a son—was of great concern to the Egyptians. Wisdom (or “Instruction”) texts from the Old Kingdom (2625-2130 BCE) through the Ptolemaic period (332-30 BCE) contain advice about this topic. The goal of these teachings was to provide their recipient with moral, ethical, religious, and practical guidelines for living. Advice concerning family matters figures prominently in these works. In a text from the Old Kingdom, dating to roughly 2300 BCE, we see the lines: “When you prosper, found your household, Take a hearty wife, a son will be born to you. It is for the son you build a house.” About a thousand years later in the New Kingdom (1539-1075 BCE), we see a very similar bit of advice: “Take a wife while you are young, that she may make a son for you while you are youthful.” A Demotic wisdom text written on a papyrus dating to the second century BCE urges the same thing: “Take for yourself a wife when you are 20 years old, that you may have a son when you are young.”

With all of this emphasis on having children, we have to keep in mind that while the birth of a child was certainly a time for celebration, it was also a time for concern. In pre-modern cultures, pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period were dangerous times for both mother and child. We do not have exact numbers on the rates of child mortality in ancient Egypt, but research suggests the percentages were likely comparable to those cultures for which we do have good data. This would suggest that approximately 20% of newborns did not reach their first birthday, and for those that did pass their first year, 35% did not live to see their fifth birthday. Work at the cemeteries of Gurob, Matmar, and Mostagedda in Egypt reveal that close to 50% of the excavated graves were for children and infants. One has to look no further than the tomb of Tutankhamun for a touching and very personal indication of this harsh reality. Included with the spectacular golden treasures buried with the king were two small coffins, which contained the mummified remains of two tiny stillborn female babies, one with a gestational age of about 5 months and the other, slightly older. These babies were presumably the offspring of Tutankhamun and his wife Ankhesenamun. King Tut died without producing a living heir.

Even with a successful birth, dangers to the child were great. Faced with such devastating odds, how did the ancient Egyptians cope? The Egyptians could seek solutions to health problems in a variety of ways. They had remarkable medical knowledge and there are a number of medical papyri, some dating as early as 1820 BCE, which contain instructions for the care of the sick and injured (Figure 2).

Figure 2: An example of an Egyptian medical papyrus dating to the New Kingdom. Known as The London Medical Papyrus, it is now housed in the British Museum (EA10059, 2) and contains medical and magical texts including incantations to prevent miscarriages. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

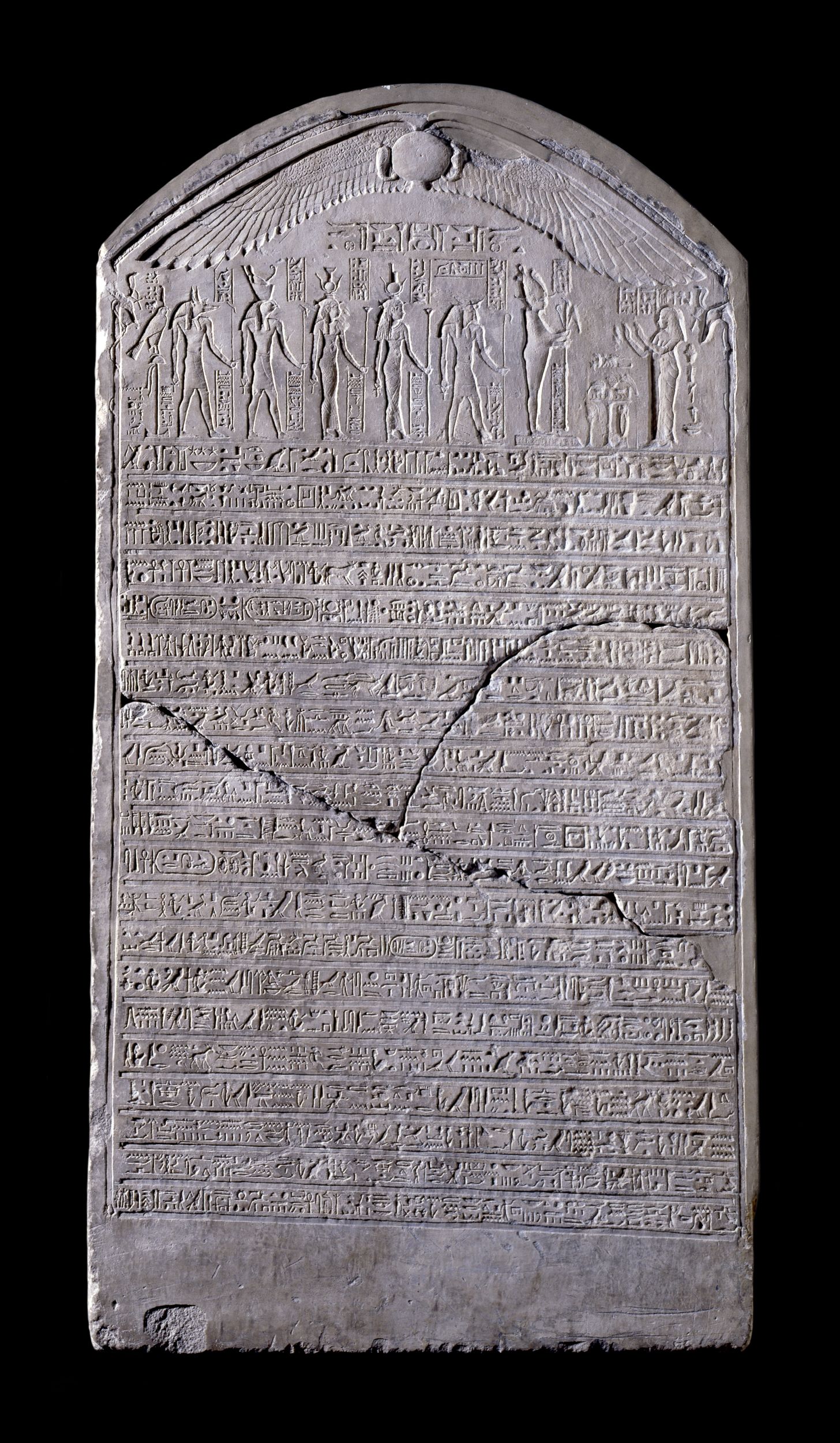

Doctors—called swnw—existed in ancient Egypt and these practitioners addressed health complaints with careful physical observation, medical prescriptions, and even simple surgical techniques. Hand in hand with practical applications of medicines and other “scientific” therapies, the ancient Egyptian doctor also made use of magical or religious interventions. It is clear from inscriptional evidence on stelae that the Egyptians would offer prayers to their gods in the hope of producing a cure. Individuals could also take personal issues such as the desire for a son before the gods. A stela belonging to a woman named Taimhotep, now in the British Museum, relates how she and her husband, Pasherenptah, had three daughters, but longed for a son. They prayed to the god Imhotep and the text tells us the god heard their prayers and granted them a baby boy whom they named after the god who aided them (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The stela of Taimhotep. Ptolemaic Period (42 BCE). British Museum EA147.

The Egyptians considered the recitation of spells and prayers and the use of magical amulets or figurines an appropriate treatment for an illness or the answer to a personal problem. Amulets are charms or talismans worn by an individual to offer protection or power. Egyptian amulets could take the shape of gods and goddesses, different animals or birds, various body parts, or other natural forms. Filled with magical or sacred potency, men and women—both the living and the deceased—used amulets in ancient Egypt. Egyptian amulets were often incorporated into jewelry and were made in a variety of materials (stone, shell, bone, ceramic, wood and metals such as bronze, gold and electrum) (Figure 4). These materials (or their intrinsic colors) often also had magical properties ascribed to them. Perhaps the most common material for amulets was faience, a type of glazed composition with a sandy core and a glassy surface. Artisans molded the faience to shape while the material was soft and then fired it. Faience came in a wide range of colors with blue-green (turquoise) being the most common. The Egyptians connected the color blue with the sky, the solar cycle, and rebirth. Green called to mind healing, growth, and the potential for life. Additionally, the word for green (w3d) could mean “whole” or “sound.”

Figure 4: Necklace with 42 gold amulets in the form of the goddess Tawaret. Eighteenth Dynasty (1539-1291 BCE). British Museum EA59418.

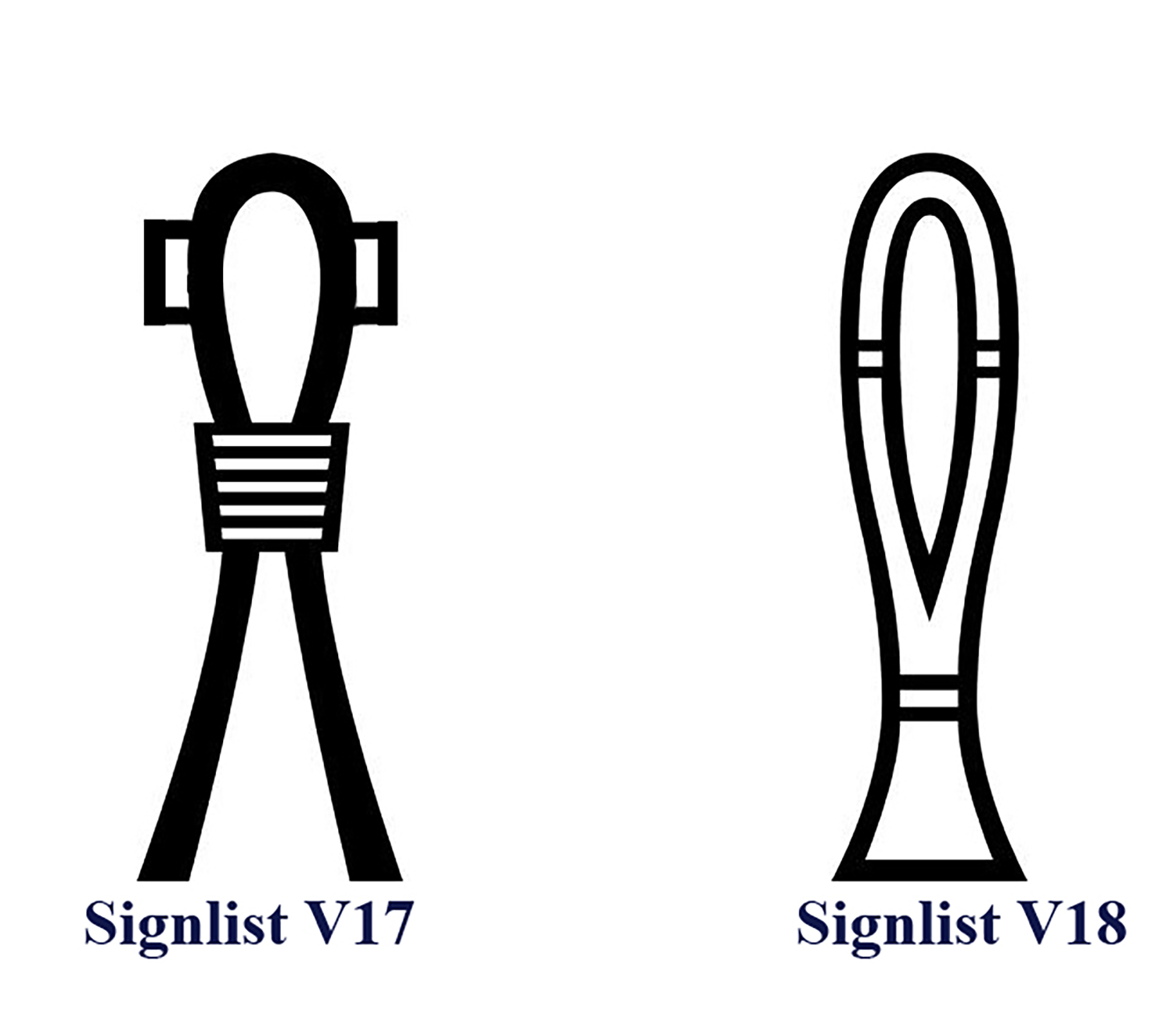

The word for amulet was s3. It is probably no coincidence that the word s3 could also mean “protection” and there are examples of amulets (s3.w ) made in the shape of the s3-sign (Figure 5). This hieroglyph (Gardiner signlist V17, var. V18) may represent a type of life preserver, perhaps made of papyrus or reeds. Decoration on the walls of Old Kingdom tombs depict boatmen engaged in riverine activity (Figure 6). In some cases, the boatmen wear a horseshoe shaped device looped across their chest. This may be the s3 life preserver, “protecting” the boatmen from an accident on the water.

Figure 5: Two variant forms of the hieroglyphic s3 sign used in writing the word “protection” and “amulet.”

Figure 6: Detail from a boating scene from the Fifth Dynasty (2500-2350 BCE) tomb of Ti at Saqqara. The man wears what appears to be a reed life preserver that takes the form of the s3 sign.

A popular type of amulet found in museum collections around the world, including the Egyptian collection at Glencairn Museum, which has more than four dozen examples, is that of the goddess Taweret (Figure 7). Most of Glencairn’s Taweret amulets are made of bluish-green faience. Taweret is a very striking goddess. Her appearance is very different from the typically slim and beautiful female deities of ancient Egypt. In comparison to these female figures, she is quite grotesque in appearance. Not unlike the devourer demon, Amamet, Taweret’s physical manifestation is a combination of dangerous and powerful animals (the crocodile, lion and hippopotamus) (Figure 8). However, unlike Amamet, Taweret’s function was protective, not punitive.

Figure 7: Examples of Glencairn Museum's Taweret amulets.

Figure 8: Scene showing the weighing of the heart. The devourer demon, Amamet, crouches at the bottom right behind the god Thoth. From the Book of the Dead papyrus of Ani dating to the Nineteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom (ca. 1292 BCE). British Museum EA10470, 3.

Taweret has the head and body of a hippopotamus. Making her even more awe-inspiring is the fact that she is not just any hippopotamus; she is a pregnant hippopotamus. Her mouth is often open, exposing her tusks and tongue in a fearsome display. Like other female deities, she wears a long wig. A flat cylindrical headdress, known as a modius, often sits atop her wig. Sometimes she is shown wearing a horned sundisk crown, seen on other goddesses such as Isis and Hathor. As noted, Taweret is not fully hippo. She has the tail of a crocodile, and the hands and feet of a lioness. She also has human breasts, which represent either the full breasts of a nursing woman, or the pendulous breasts of an elderly woman. She does not stand on all fours like a typical hippopotamus; usually she stands upright on her hind legs.

Her very name emphasizes her power. Taweret (T3-wr.t) means “the great (female) one.” Greeks rendered her name as Thoeris. Further emphasizing her protective nature, Taweret usually carries or rests upon the s3 symbol, which reads, “protection.” In her role as an apotropaic figure, she can also brandish a knife that she would use to ward off evil or harmful forces.

Hippo imagery appears quite early in the Egyptian artistic canon. Hippos together with other riverine creatures, such as crocodiles, appear on Predynastic pottery dating as early as 3850 BCE. Several ancient Egyptian deities, both male and female, can take the form of a hippopotamus. As a destructive force of chaos, the god Seth could take the form of a hippopotamus. Seth appears in this guise on the walls of the temple of Horus at Edfu where he battles Horus unsuccessfully for the throne of Egypt. As noted above, the devourer demon, Amamet, was also part hippo.

Taweret was one of several goddesses including Ipet (“the Nurse”), Reret (“the Sow”), and Hedjet (“the White One”) who could take the shape of a hippopotamus. All of these goddesses were associated with pregnancy and protection, and they are often difficult to distinguish from one another (Figure 9). By the Old Kingdom (2625-2130 BCE), amulets in the shape of an upright hippopotamus appear, perhaps depicting Taweret or one of the other protective hippo goddesses

Figure 9: The goddess Ipet wearing a horned sundisk crown. Ipet is depicted in a form identical to that of Tawaret. From the Book of the Dead papyrus of Ani dating to the Nineteenth Dynasty of the New Kingdom (ca. 1292 BCE). British Museum EA10470, 37.

Taweret was a popular domestic goddess. Much of her cult took place in domestic shrines rather than in large state-run temples, however, she may have had a sanctuary at Deir el-Medina. Apotropaic images of Taweret occur on the outside of Ptolemaic temples to ward off evil, much in the same way that gargoyle imagery protected Christian churches. Taweret’s image appears on household items such as beds, stools, and headrests. Votive stelae attest to her role as a healing deity (Figure 10). Taweret's popularity spread outside the borders of Egypt, and representations of Taweret turn up in Crete and at the sites of Kerma and Meroë in Nubia.

Figure 10: A limestone votive stela depicting the goddess Tawaret and the god Amun-Re. New Kingdom (1539-1075 BCE). University of Pennsylvania Museum 69-29-65.

A constellation in the form of Taweret is depicted in the Theban tombs of Tharwas (tomb 353 in Western Thebes) and Senenmut (tomb 232 in Western Thebes), and in the Osiris Chapel in Medinet Habu as part of a scene showing the northern sky. An epithet, or nickname, of Taweret is “She of the Pure Water,” which may refer to her connection to the Nile River. Taweret was associated with the inundation of the Nile because of her appearance as a riverine creature. She is also called “The One Who is in the Waters of Nun” in a shrine at Gebel es-Silsila. Ostraca from the site of Deir el-Medina indicate that Taweret could have had a demonic aspect, and her composition from ferocious creatures may have connected her with Seth, the god of chaos.

Pregnant and nursing women used images of the fearsome Taweret and the equally strange-looking god Bes to keep evil away from their infants (Figure 11; Figure 12). Another epithet of Taweret is she “Who Removes the Water,” which may allude to the process of birth. From the Amarna period of the Eighteenth Dynasty—when worship of gods other than Aten was proscribed—excavators found examples of Taweret images from the site of Tell el-Amarna, the center of the worship of the Aten. Taweret’s presence at this site emphasizes the importance of this guardian of pregnant woman in the lives of the common people, who did not cease their worship of this popular goddess even during the Amarna period.

Figure 11: Faience plaque of the god Bes. Dynasty 21-25 (1075-656 BCE). University of Pennsylvania Museum E14358.

Figure 12: Bes and the son of the author, Alexander Wegner, seen at the site of Dendereh. Like Tawaret, Bes protected mothers and babies.

It is really in the realm of protecting pregnant women and their babies that Taweret is prominent. In addition to amulets, which may have been worn by women, images of Taweret (and other protective hippo goddesses) appear on a variety of magical artifacts, which seem to be closely connected to birth magic. Figurines of Taweret, such as the one in Glencairn’s collection (Figure 13; Figure 14), may have been given as gifts, kept in household shrines, or dedicated at local temples in hope of, or thanks for, a successful birth. Images of Taweret (and other protective deities) frequently decorate objects connected closely to pregnancy, birth and care of newborns, such as magical wands, feeding cups and an as-of-now unique object, a painted birth brick. Let’s consider each of these categories.

Figure 13: Glencairn Museum's Taweret figurine. Late Period. Glencairn Museum E66.

Figure 14: A painted limestone statuette of the goddess Taweret. Date unknown. University of Pennsylvania Museum L-55-211.

Representations of protective deities, many of whom also protected the sun god on his dangerous journey through the nighttime sky, adorn the so-called “magical wands” dating to Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (1980-1630 BCE). In many scenes, the deities hold knives to combat evil forces. A hippo goddess (most likely Taweret) appears on approximately 75% of the known examples. In addition to depictions of lions, frogs, vultures and jackals, a wand in the Penn Museum has an image of a female hippo deity who stands on her hind legs and leans on the s3 hieroglyph (Figure 15). Artisans carved these wands from hippopotamus tusks. The wands often have wear patterns on the tip indicating that people used them in a rather specific way. A practitioner of magic would draw the wand through the sand and create a protective circle around individuals, for example, a woman in labor or a sleeping child. Perhaps a parallel is drawn between the individual protected by the magical wand and the sun god—just as the sun god travels through the night unmolested by evil spirits, so too will the protected individual remain unharmed. The knives also had a funerary use and they have been found in tombs where they were placed to help ensure the rebirth of the deceased—again echoing the successful passage of the sungod through the night to be reborn again at dawn. Inscribed examples of these wands contain texts, which say things like: “A recitation by the many protectors: We have come that we may extend our protection around the healthy child Minhotep, alive, sound and healthy, born of the noblewoman Sitsobek, alive, sound and healthy.” Similarly, there are examples of feeding cups for infants decorated with comparable imagery (including depictions of Taweret). The images on the cup would imbue the contents with magical power and would protect the baby who drank the liquid. Related protective magical objects include vessels from the New Kingdom that take the shape of pregnant women whose rounded bodies echo the form of the goddess Taweret, and there are examples of “Taweret vessels” which have openings at the nipples, presumably for pouring mother’s milk.

Figure 15: Magical wand made of hippopatamus ivory inscribed with apotropaic figures. A standing hippo goddess, possibly Taweret, is on the left. Twelfth Dynasty (1938-1759 BCE). University of Pennsylvania Museum E2914.

Even though there are a number of medical papyri dealing with women’s health issues, there is nothing in the medical texts concerning the birthing process. In order to understand what may have happened during birth in ancient Egypt we have to turn to literary works, such as the story found in Papyrus Westcar, wherein a woman named Rededet gives birth to royal triplets with assistance from the goddesses Isis, Nephthys, Meskhenet and Heket. The text tells us: “Isis placed herself in front of her, Nephthys behind her and Heket hastened the birth.” The divine “midwives” address the baby in the womb and tell the child to come forth. After each baby is born, the goddesses wash the baby, cut his umbilical cord, and place him on a [couch of] brick.

The appearance of a “brick” in this story troubled Egyptologists for many years. What was this brick, or “couch” of bricks, on which the baby was placed? In 2001, the explanation became a bit clearer when Joe Wegner, an archaeologist at the Penn Museum discovered a “birth brick” at the site of Abydos, Egypt (Figure 16; Figure 17). The brick came from an area of the house associated with women. Many inscribed clay seal impressions also found in this area have the name of a woman called Renseneb, who is described in the texts as a “noblewoman and king’s daughter.” This woman, who lived during Egypt’s Thirteenth Dynasty (1759-1630 BCE), may have been a princess who was married to one of the town’s mayors.

Figure 16: Photograph of the painted mudbrick birth brick discovered at South Abydos, Egypt.

Figure 17: Reconstruction painting of the scene of the mother and newborn baby on the bottom of the brick. Female attendants who likely respresent goddesses flank the seated mother. Hathor-headed staffs frame the scene.

The brick in question, which measures 14 by 7 inches, was probably one of a pair used by a woman in labor. Ancient Egyptian women gave birth in a squatting position. The brick would have been used to support a woman's feet while crouched during childbirth. The ancient brick still preserves colorful painted imagery on five of its six sides (Figure 18). A scene of a seated mother holding a newborn baby decorates the bottom surface. The child is clearly a male, as he is painted red, following the conventions for Egyptian art, which depicted males with reddish brown skin and females with a lighter skin tone. Two female attendants flank the seated mother on each side. One female figure kneels in front of the seated woman. The other female stands behind the mother placing her hand on the woman’s shoulder. On either side of the scene, two staffs topped with an image of the goddess Hathor, a cow goddess closely associated with birth and motherhood, appear.

Figure 18: Reconstructed painting of the scene of the mother and newborn baby on the bottom of the brick.

The scenes around the four sides depict divine beings, many of whom are similar to those seen on the magical wands (Figure 18a). The figures on the brick include an anthropomorphic deity, a nude blue goddess, a leonine deity, a baboon, a coiled cobra, and a standing desert cat. A hippo deity who may be Taweret also appears on the side of the brick. The purpose of all of these divine images was to protect and aid the mother and baby at the time of birth.

Figure 18a: Reconstructed line drawing of figures on the edges.

The Egyptians likened the birth of a child to the rising of the sun at daybreak. The magical practices of childbirth protected a newborn baby in a way that parallels Egyptian myths describing how the young sun god required protection from hostile forces. On the birth brick from the Abydos excavation the sun god is shown in symbolic form in the guise of a desert cat (Figure 19). Images of these guardians of the sun god magically provided similar protection for mother and child.

Figure 19: Reconstructed painting of the image of the desert cat who represents the sun god.

Studies of modern folk magic in Egypt indicate that women wishing to become pregnant still regard Taweret as a helper. The Egyptian Museum in Cairo houses a beautiful statue of Taweret carved from a hard dark stone (Figure 20). The belly of the statue has a highly polished sheen. This luster is not from ancient artisans polishing the stone, but rather from (modern) women who came to the museum and rubbed the belly of the statue hoping that the pregnant deity would help them to conceive. Nowadays, a glass vitrine protects the statue and women can no longer touch it. However, women hoping to have a child reportedly still make visits to the museum just to see the statue. This contemporary folk practice makes it clear that for thousands of years the goddess Taweret has offered protection and succor to expectant mothers and women wishing to become pregnant.

Figure 20: Taweret statue in the Cairo Museum.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Associate Curator, Egyptian Section, Penn Museum

University of Pennsylvania

Select Bibliography

Allen, James P. 2005. The art of medicine in ancient Egypt. New York; New Haven; London: Metropolitan Museum of Art; Yale University Press.

Andrews, Carol 1994. Amulets of ancient Egypt. London: The British Museum Press.

Chamberlain, Geoffrey 2004. Historical perspectives on health: childbirth in ancient Egypt. The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 124 (6), 284-286.

Fischer, Henry G. 1987. The ancient Egyptian attitude towards the monstrous. In Farkas, Ann E., Prudence O. Harper, and Evelyn B. Harrison (eds), Monsters and demons in the ancient and medieval worlds: papers presented in honor of Edith Porada, 13-26. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern.

Gundlach, Rolf. Thoeris. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie, 6: 494–497. Wiesbaden, 1985.

Lesko, Barbara S. 1999. The great goddesses of Egypt. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Lichtheim, Miriam 2006. Ancient Egyptian literature. A book of readings, volume I: The Old and Middle Kingdoms. Berkeley, CA; London: University of California Press.

Lichtheim, Miriam 2006. Ancient Egyptian literature. A book of readings, volume II: The New Kingdom. Berkeley, CA; London: University of California Press.

McDowell, A.G., Village Life in Ancient Egypt. Laundry Lists and Love Songs, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1999.

Nunn, John F., Ancient Egyptian Medicine, London, British Museum Press, 1996.

[Omm Sety] 2008. Omm Sety's living Egypt: surviving folkways from Pharaonic times. Introduction by Walter A. Fairservis. Edited by Nicole B. Hansen. Chicago, IL: Glyphdoctors.

Pinch, Geraldine 1994. Magic in ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press.

Ritner, Robert Kriech 1993. The mechanics of ancient Egyptian magical practice. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 54. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Robins, Gay 1993. Women in ancient Egypt. London: British Museum Press.

Robins, Gay 1994-1995. Women & children in peril: pregnancy, birth & infant mortality in ancient Egypt. KMT 5 (4), 24-35.

Roth, Ann Macy and Catharine H. Roehrig 2002. Magical bricks and the bricks of birth. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 88, 121-139.

Silverman, David P., Josef W. Wegner, and Jennifer Houser Wegner 2006. Akhenaten and Tutankhamun: revolution and restoration. Philadelphia, PA: Museum.

Simpson, William Kelly (ed.) 2003. The literature of ancient Egypt: an anthology of stories, instructions, stelae, autobiographies, and poetry, third ed. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

Verner, Miroslav 1969. Statue of Twēret (Cairo Museum no. 39145) dedicated by Pabēsi and several remarks on the role of the hippopotamus goddess. Zeitschrift für ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 96 (1), 52-63.

Wegner, Jennifer Houser 2001. Taweret. In Redford, Donald B. (ed) The Oxford encyclopedia of ancient Egypt. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wegner, Josef 2009. A decorated birth-brick from South Abydos: new evidence on childbirth and birth magic in the Middle Kingdom. In Silverman, David P., William Kelly Simpson, and Josef Wegner (eds), Archaism and innovation: studies in the culture of Middle Kingdom Egypt, 447-496. New Haven, CT; Philadelpia, PA: Department of Near Eastern languages and civilizations, Yale University; University of Pennsylvana Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Wegner, Joseph 2010. Tradition and innovation: the Middle Kingdom. In Wendrich, Willeke (ed.), Egyptian archaeology, 119-142. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Weingarten, Judith 2013. The arrival of Egyptian Taweret and Bes[et] on Minoan Crete: contact and choice. In Bombardieri, Luca, Anacleto D'Agostino, Guido Guarducci, Stefano Valentini, and Valentina Orsi (eds), SOMA 2012. Identity and connectivity: proceedings of the 16th Symposium on Mediterranean Archaeology, Florence, Italy, 1-3 March 2012 1, 371-378. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Wilkinson, Richard H. 2003. The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.