Glencairn Museum News | Number 8, 2015

Camping in Jerusalem: April 20, 1878. Pitcairn (left) and Benade (sitting, right) near the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem. Photograph courtesy of the Academy of the New Church Archives, Swedenborg Library, Bryn Athyn.

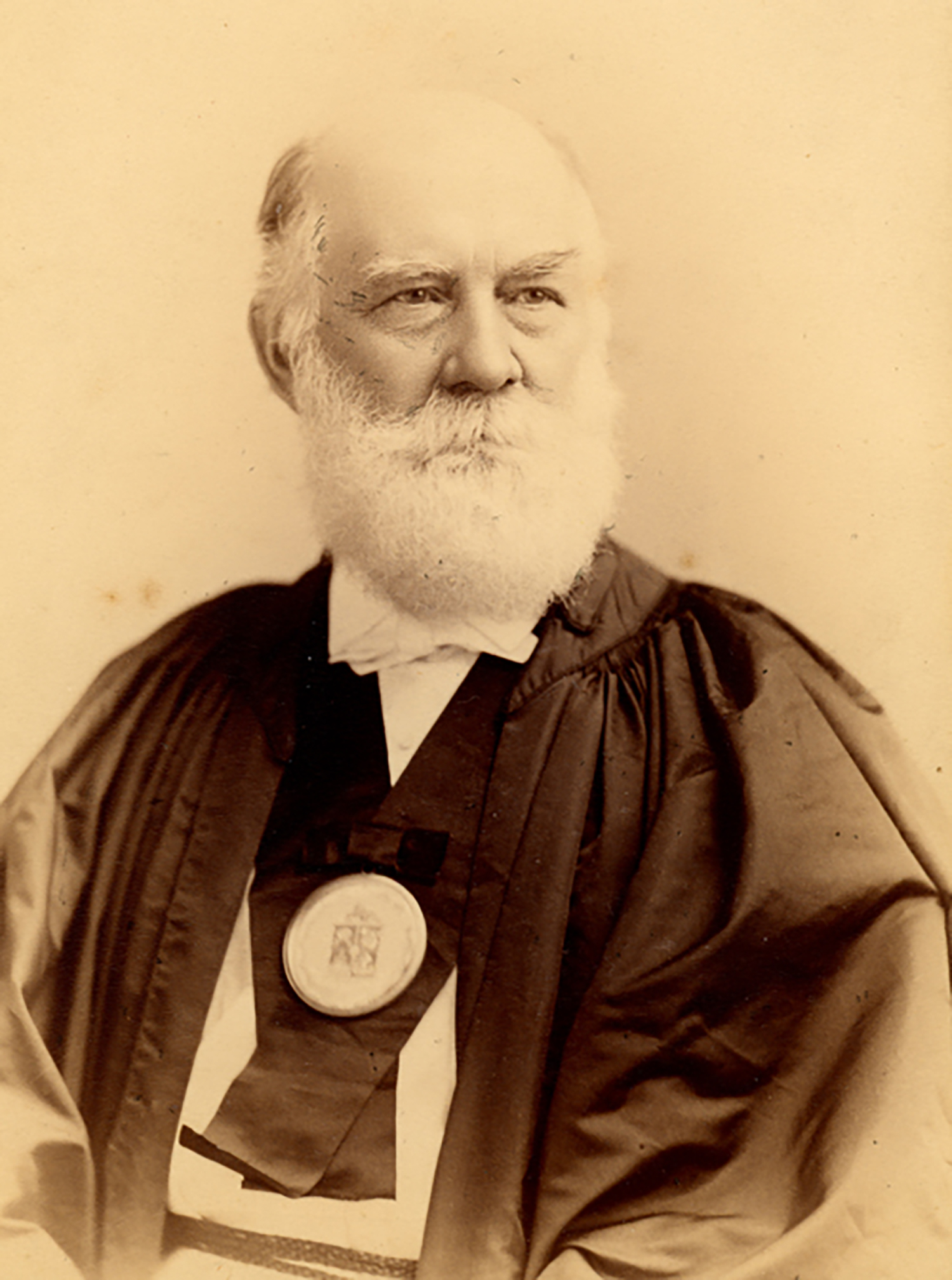

Figure 1: William Henry Benade (1816-1905). Photograph courtesy of the Glencairn Museum Archives.

The Egyptian collection at Glencairn Museum, established in 1878, was assembled primarily by four men: the Reverend William Henry Benade (a Christian pastor, and later a bishop), John Pitcairn and his son Raymond (industrialists and philanthropists), and Rodolfo Vittorio Lanzone (an Italian Egyptologist and collector of antiquities). Benade and Pitcairn had earlier been instrumental in founding the Academy of the New Church, then located on Cherry Street in Philadelphia. Benade and Pitcairn were not present to witness the long-anticipated opening of the Academy in September of 1877, as the previous June they had boarded the White Star Liner Germanic, bound for an extended tour of Europe, Egypt and the Holy Land. Benade would later reflect on their three-month Egyptian excursion in a letter home to a member of the Academy:

“Our voyage up and down the Nile has been a long, but a very delightful one. We have seen much, and I trust, have learnt something. This is a wonderful country, a country of ruined Temples, Palaces and Tombs, which teaches more of truth in its ruins, than most other countries do in their beauty and glory . . . The pictures on the walls of some of the Temples, all of them religious, are lovely in the extreme, not so much as mere works of Art, but as expressions of the sentiment of profound reverence for the Divine Being, coupled with a deep, confiding love.”2

Figure 2: Travel diary of John Pitcairn, 1878. Photograph courtesy of the Glencairn Museum Archives.

While in Florence for the Oriental Congress, Benade dined at the home of Robert Hay, the son and namesake of the well-known Scottish traveler and collector of Egyptian antiquities.3 The younger Hay was married to a Florentine lady, and it may have been during his visit to their home that Benade first conceived the idea of establishing a museum for the Academy of the New Church. Although Benade and Pitcairn had engaged in some casual collecting during their Egyptian trip earlier that year, the idea of a museum was never mentioned in Pitcairn’s detailed trip diary or in the letters they wrote home to members of the Academy. But now, after visiting the Italian home of the Hay family, Benade makes the following remarks:

“They reside on the third floor of a fine old palace, in large, airy rooms, beautifully frescoed, and have gathered around them many works of art; something which is easily done in Florence, at this time. At a comparatively small cost, one could collect a large cabinet of curious and beautiful things in bronze, marble and wood, which have become marketable, in consequence of the breaking up of the Monasteries, and of the decay of old families, who have been obliged to sell the collections of ages, in order to gain a livelihood.”4

Benade’s observation that “one could collect a large cabinet of curious and beautiful things” is a clear reference to the 19th-century practice of assembling a “cabinet of curiosities,” a special room decorated with a wide range of artifacts, often the result of travels abroad. This forerunner to modern museums, prevalent in both Europe and America, originated in the Italian “cabinets” of the 16th and 17th centuries. Benade’s comment about old Italian families being “obliged to sell a collection of ages, in order to gain a livelihood” is especially interesting in light of what happened next: later that month Benade wrote to John Pitcairn to ask if he would be willing to purchase a collection of “about 1300” Egyptian antiquities from Rodolfo Vittorio Lanzone (1834-1907), an Italian from a stately family.

Figure 3: Rodolfo Vittorio Lanzone (1834-1907). Photograph c Soprintendenza BAP e AE—used with permission.

William Benade had met Lanzone while visiting the Turin Museum, where Lanzone was employed as an Egyptologist:

“There is not much to interest one in the city, as such, but the Egyptian Museum is one of the best I have seen, in some respects, more interesting than any. The collection was formed by Signor Drovetti, French Consul in Egypt, at a time when there [were] but few collectors in the field, and he succeeded in obtaining many valuable things, especially in the way of Statues and Statuettes of the Divinities, and Papyri. In addition, I had the good fortune, immediately on my entrance into the Museum, to make the acquaintance of Professor Lanzone, the Assistant Conservateur, and from him I have gained a great amount of information, which he gathered during a twenty years’ residence in Africa. He was an enthusiastic collector of Arabic MSS and Egyptian Antiquities, in fact, he spent his patrimony in that way, and is now in a subordinate office here, as a means of earning a livelihood. He speaks English very well, and as he has made a study of the Mythology of the Egyptians, with the view of publishing something on the subject, we were soon on excellent terms . . . Our long conversations on this and other subjects, fully opened the Professor’s heart, and his closets. From the latter he brought forth a large and beautiful collection of Egyptian monuments, made during his long stay in Egypt; a collection rich in statuettes of the Divinities—clay and bronze—containing many things not to be found elsewhere. As he has made use of a greater part of this collection in the preparation of his work on the Egyptian Divinities, he offered to dispose of so much of it, as he did not require, and of the remainder, after he had published descriptions of certain things. The portion he offers for sale, consists of about 1300 pieces—larger and smaller—in bronze, clay and wood—besides a complete mummy dress of beads. For this collection he asks ₤300; a sum that seems large, but which is much less than they would cost if purchased by the piece, even in Egypt. It is a rare chance, if you think you can or ought to afford it. Possibly too, he might take ₤250. I am anxious to see these things go to America, and if our means will not admit of their purchase, I shall write to Mr. Drexel, who I am sure will buy them at once—and we can probably have the benefit of them, as he proposes to leave his collection for public uses. The Professor’s offer is open to us—as long as we may wish to consider it, as he does not wish to leave what he has to the Museum here.”5

Figure 4: Egyptian amulets from the Lanzone collection, now in the collection of Glencairn Museum.

Lanzone, who was an Arabist as well as an Egyptologist, was on the staff of the Turin Museum from 1872 to 1895. A minor—but by no means insignificant—figure in the history of Egyptology, little information has survived about him; however, in the 1970s Silvio Curto was able to gather enough material to write a brief biography to mark the occasion of the reprinting of Lanzone’s Dizionario di Mitologia Egizia.6 According to Benade’s letter to Pitcairn,7 Lanzone used objects from his personal Egyptian collection “in the preparation of his work on the Egyptian Divinities”; however, it is clear that the Turin Museum’s collection was his primary source.8 Lanzone’s Dictionary received favorable reviews and was used extensively by early Egyptologists; Budge, for example, called it “one of the most valuable contributions to the study of Egyptian mythology ever made.”9 Rodolfo Lanzone was born in 1834 in Cairo, the son of Luigi Lanzone, who had been forced to leave Italy for political reasons. The elder Lanzone worked as a medical doctor in Cairo for 40 years. By the time the family returned to Italy, Rodolfo had spent many years living, traveling, and collecting antiquities inside Egypt. Heinrich Brugsch, writing about 19th-century Europeans who assembled Egyptian collections while living in Egypt, notes, “the Italian Lanzone, at present one of the conservators of the Egyptian Museum in Turin, possessed true treasures in his cabinet of antiquities selected with great care.”10 As to the question of how collections like Lanzone’s were formed, Brugsch says, “As sellers of the antiques there regularly appeared Bedouins, who wandered about the country in order to buy up, at cheap prices, finds accidentally made by the peasants working on their farms, or themselves to carry out secret excavations, usually at places lying hidden, and at night . . .”11 A photograph of one of the objects in Lanzone’s collection—a 22nd Dynasty statuette of Osorkon I with gold inlay—was published in 1884, along with a lively account of how Lanzone witnessed its discovery at Shibin el-Qanatir. Attracted by the cries of local farmers, Lanzone “found that they had unearthed a small terra-cotta vase, containing bronze coins mixed with fragments of statuettes, and close to them a somewhat large oxidized mass, of no particular form. When cleaned and the oxidation removed, it proved to be the statuette of Uasarkan I . . .”12 The Osorkon I statuette is now in the collection of the Brooklyn Museum (accession no. 57.92).13 On receiving Benade’s letter, Pitcairn writes back that he is “favorably impressed” with the idea of purchasing the Lanzone collection, but wishes to “consider the matter more fully.”14 Benade responds by pointing out to Pitcairn that “it is a very valuable collection, for the purposes of mythological study.”15 After an unsuccessful attempt to bring the price down, Pitcairn agrees to pay ₤300, but requests that Lanzone “furnish us with an inventory, or a list of objects.”16 In December of 1878, Benade writes home to Dr. F. E. Boericke with evident excitement: “When John and I return, we hope to bring with us a fine collection of Egyptian Antiquities, which I found in Turin, and which John has generously purchased. These things will make the beginning of a Museum for the Academy. I hope that all our friends will bear in mind that we shall need a Museum, and will collect whatever they can find, that may be of use for such a purpose.”17 The Lanzone collection was sent to Philadelphia, but unfortunately the inventory of objects requested by Pitcairn has never been found.18 With the idea of “a Museum for the Academy” now firmly in mind, Benade continued collecting. Before leaving Italy, he shipped back to Philadelphia, among other things, two “not so small” cases of Etruscan antiquities.19 According to Benade, “you can buy much here, at almost your own prices. So many things have been sold by old families, that the market is overstocked.”20 With Benade’s sponsorship and Pitcairn’s patronage, the Academy of the New Church also made possible the publication of an Amduat papyrus in the collection of the Turin Museum—one of the first publications of this genre. Benade writes to Pitcairn, “Professor Lanzone proposes to do the lithographing himself, to save expense, and also to secure accuracy.”21 A comparison of his lithograph with modern photographs of the papyrus shows Lanzone to have been a skilled artist and accurate copyist (Figures 5, 6). The 1879 lithograph, Le Domicile des Esprits, Papyrus du Musee de Turin, which includes introductory notes by Lanzone, remains the only published source for this copy of the Amduat.22

Figure 5: A portion of the twelfth hour of the Amduat, from a papyrus in the collection of the Egyptian Museum of Turin (accession no. 1776). Photograph © Fondazione Museo Antichità Egizie di Torino—used with permission.

Figure 6: A portion of the twelfth hour of the Amduat in the collection of the Egyptian Museum of Turin as published by Rodolpho Vittorio Lanzone in his 1879 lithograph, Le Domicile des Esprits, Papyrus du Musée de Turin.

After returning from Europe in August of 1879, Benade moved the Egyptian collection into the parlor of his home on Friedlander Street in Philadelphia, a small three-story house that would also serve as classroom space for the Academy’s College and Theological School. The quarters were cramped, and it was only possible to unpack a portion of the Lanzone collection,23 but Benade writes to a friend, “Don’t laugh at the idea of a Museum—we must have a place for our Egyptian Pantheon, and Etruscan Pottery . . .”24 Benade’s lecture series in Philadelphia, “Conversational Lectures on Antiquities in the Light of the New Church,” began on November 15, 1879, with the twelfth and last lecture taking place the following spring. The presentations were delivered in one of the Academy’s schoolrooms for an admission fee of ten cents per lecture.25 Benade illustrated his talks with the photographs he and Pitcairn had acquired in Egypt, together with a variety of diagrams and temple plans. He also showed his audience objects from the Academy’s Egyptian collection, including shabtis and statuettes. According to one reporter, “After giving us so much spiritual food, Mr. Benade showed us some material food in the form of Egyptian bread, probably thousands of years old. But nobody present seemed to care to taste it.”26

Figure 7: The first home of the Academy’s Egyptian collection, on Friedlander Street in Philadelphia.

Over the next several decades, as the Academy moved from place to place in Philadelphia, the Egyptian collection moved with it. Objects were always on exhibit and accessible to students, in accordance with Benade’s belief that “a good Museum is a necessary adjunct of a good School.”27 In the 1880s at least one class was formed at the Academy “for the study of Hieroglyphics.”28 Benade, now a bishop, paid the tuition fees “out of his small income” for several Academy students to study Egyptology and Assyriology under Hermann Hilprecht at the University of Pennsylvania.29 One of these students was Carl Theophilus Odhner, who would go on to teach archaeology at the Academy. In 1897 the Academy of the New Church moved from Philadelphia to a campus in nearby Bryn Athyn, and in 1902 the Egyptian collection and the rest of the museum’s holdings were given a special room in Benade Hall, the new school building. Within a few years Odhner had completed a catalog of the objects in the Egyptian collection, assisted by his students.30

Figure 8: Objects from the Lanzone collection, now in Egyptian Pantheon exhibit in the Egyptian Gallery at Glencairn Museum.

In 1912, the collection was moved into a large building financed by John Pitcairn to house the Academy’s museum and library. Most of the larger Egyptian objects in Glencairn Museum’s collection were purchased in the 1920s by Raymond Pitcairn, John’s son, and kept in the Academy’s museum. (Several of these objects have received international attention, such as the 4,400-year-old Egyptian “spirit door,” from the 5th Dynasty tomb of Tep-em-ankh in the western cemetery of the Great Pyramid of King Khufu. In 2011 Tep-em-ankh’s door was sent on loan to the Roemer- und Pelizaeus- Museum in Hildesheim, Germany, where it was part of a major international exhibition, Giza: Gateway to the Pyramids.) In 1980 all of the collections in the Academy’s museum were moved from the library building to Glencairn, where they merged with the Pitcairn collections to create what we know today as Glencairn Museum.

Ed Gyllenhaal

Curator, Glencairn Museum

“From Parlor to Castle: The Egyptian Collection at Glencairn Museum” is available here.

Endnotes

1 For more information about these objects see D. Romano and I. Romano, Catalogue of the Classical Collections of the Glencairn Museum (Bryn Athyn, Pennsylvania, 1999).

2 Benade to Maria Hogan, Cairo, April 7, 1878.

3 After his death in 1863 the elder Robert Hay’s collection was sold to the British Museum and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

4 Benade to McCandless, Venice, October 10, 1878.

5 Benade to Pitcairn, Turin, October 26, 1878.

6 R. V. Lanzone’s Dizionario di Mitologia Egizia (1975: 7-12). Lanzone published his dictionary of Egyptian mythology in six parts (1312 pages, 408 plates) from 1881-1886. Dizionario di Mitologia Egizia was reprinted in three volumes in 1974, with corrections and updates by Mario Tosi. A fourth volume, consisting of material previously left unpublished by Lanzone, appeared in 1975 (M. Tosi (ed.), Dizionario di Mitologia Egizia, 4 vols. (Amsterdam, 1974-1975); J. Johnson, “Dizionario di Mitologia Egizia,” JNES 38 (1979), 70).

7 Benade to Pitcairn, Turin, October 26, 1878.

8 R. V. Lanzone, Dizionario di Mitologia Egizia. Mario Tosi (ed.). 4 vols. (Amsterdam, 1974-1975), Foreword.

9 E. A. W. Budge, The Gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian Mythology. 2 vols. (London, 1904), xi.

10 H. Brugsch, My Life and My Travels. Ruth Magurn (trans.), George Laughead Jr. and Sarah Panarity (eds.). http://www.vlib.us/brugsch/ (1992).

11 Ibid.

12 G. Gonino, Untitled. Proceedings of the Society of Biblical Archaeology 6 (1884), 205.

13 The Osorkon I statuette at the Brooklyn Museum (57.92) and the 1,115 objects (mostly amulets, bronzes, and shabtis) comprising the Lanzone collection at Glencairn Museum are the only objects extant from Lanzone’s personal collection. He also acquired two fragments of a text from the Ptolemaic Period—a version of the Papyrus of Lake Moeris (R. V. Lanzone, Le Papyrus du Lac Moeris (Turin, 1896))—but according to Silvio Curto the location of these is unknown (“Rodolfo Vittorio Lanzone,” in R.V. Lanzone, Mario Tosi (ed.), Dizionario di Mitologia Egizia. 4 vols. (Amsterdam, 1975), viii).

14 Pitcairn to Benade, Paris, October 29, 1878.

15 Benade to Pitcairn, Rome, November 2, 1878.

16 Pitcairn to Benade, Paris, November 17, 1878.

17 Benade to Boericke, Rome, December 4, 1878.

18 Kate Benade, William Henry Benade’s widow, wrote in response to a request from the Academy’s librarian that no such list was found among his papers (Benade to Reginald Brown, London, February 14, 1924). According to one published source, in 1916 there were 1,125 objects in the Lanzone collection (C. Lj. Odhner, “The Lanzone Collection,” Journal of Education of the Academy of the New Church 15:2 (1916), 103). An inventory taken by the museum in 1974 listed 1,115 objects in the collection.

19 Benade to Boericke, Rome, December 4, 1878; see also Romano and Romano, Catalogue of the Classical Collections.

20 Benade to Pitcairn, Rome, November 12, 1878.

21 Benade to Pitcairn, Turin, October 26, 1878.

22 A copy of F. Vieweg, Le Domicile des Esprits, Papyrus du Musee de Turin (Paris, 1879) is in the Glencairn Museum Archives. (Benade had worked with Vieweg previously and recommended him to Lanzone.) This Amduat papyrus carries Turin Museum accession no. 1776 and is described in A. Fabretti, F. Rossi, and R. V. Lanzone, Catalogo Generale dei Musei di Antichita: Regio Museum di Torino (Turin, 1882).

23 Odhner, Journal of Education of the Academy of the New Church 15:2, 103.

24 Benade to Walter Childs, Philadelphia, November 10, 1879.

25 J. Whitehead, “From Philadelphia,” New Jerusalem Messenger 37:23 (1897), 316.

26 Shreck, Morning Light: A New-Church Weekly Journal 3, 98.

27 Benade to Childs, Philadelphia, April 17, 1882.

28 Benade to Childs, Philadelphia, April 18, 1884.

29 Kate Benade to H. P. Chandler, Bryn Athyn, December 1, 1913.

30 E. Sherman, “Report of the Girls’ Seminary,” Journal of Education of the Academy of the New Church 1906, 31.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.