Glencairn Museum News | Number 7, 2015

Glencairn's seated bronze cat votive, Late Period (664-332 BCE).

“The Instruction of Onchsheshonqy,” a Demotic wisdom text of the Ptolemaic period, contains over 500 lines of advice and teachings meant to instruct the average person on how to live a successful and proper life. Amongst the recommendations to be modest, self-controlled, and generous, there is the sage warning: “Do not laugh at a cat” (Figure 1). At first glance, this may seem like a strange addition to a text that contains advice like:

“You may stumble with your foot in the house of a great man; you should not stumble with your tongue.”

“Do not often get drunk, lest you go mad.”

“Take for yourself a wife when you are 20 years old, that you may have a son when you are young.”

“Let your good deed reach the one who has need of it.”

“The companion of a fool is a fool. The companion of a wise man is a wise man.”

“Be small in wrath and your respect will be great in the hearts of all men.”

Figure 1: Cats are a part of dig house life in Egypt. This Abydos dig house cat (left), known as Twinkie, helps to illustrate a maxim from the Demotic Wisdom Text, “The Instruction of Onchsheshonqy”: “A cat that loves fruit hates him who eats it” (Onchsheshonqy 23/15). A not very regal Abydos dig house cat (right) makes it very hard to obey Onchsheshonqy’s advice to not laugh at a cat.

However, if we consider the position and importance of the cat in ancient Egypt, this line is not so peculiar at all. It probably does not refer to laughing at the common domestic house cat (although hundreds of YouTube cat videos are admittedly very funny; how does that big cat get in all those tiny boxes?), but probably refers to advice not to scoff at one of the many deities who could appear in feline form.

Deities in ancient Egypt could appear in a variety of forms. Some gods and goddesses take a fully human appearance; others are depicted with animal heads and human bodies, while yet others could take completely animal or composite animal forms. Many gods were also associated with sacred animal avatars that the Egyptians believed could house the ba (a spiritual form) of a particular deity. For example, the god Amun, a creator god who usually takes a human form, could also appear as a ram or a goose (Figure 2). The god of wisdom, Thoth, was most often shown as a man with the head of an ibis, but could also appear fully in ibis form, or as a baboon (Figure 3). Quite a few goddesses (and even some male deities) could take feline or leonine forms.

Figure 2: A wooden statue of the god Amun, Third Intermediate Period (1075-656 BCE). Penn Museum E14325.

Figure 3: A bronze votive statuette of the god Thoth, Ptolemaic Period (305-30 BCE). Penn Museum E14298.

Let’s consider the role of the cat in ancient Egypt and look at the cat’s larger and more powerful “cousin,” the lion. As we shall see, cats and lions are often very closely linked. Understanding the role and importance of cats and lions in ancient Egypt will help us better appreciate the feline imagery on view in the Egyptian Gallery at Glencairn Museum.

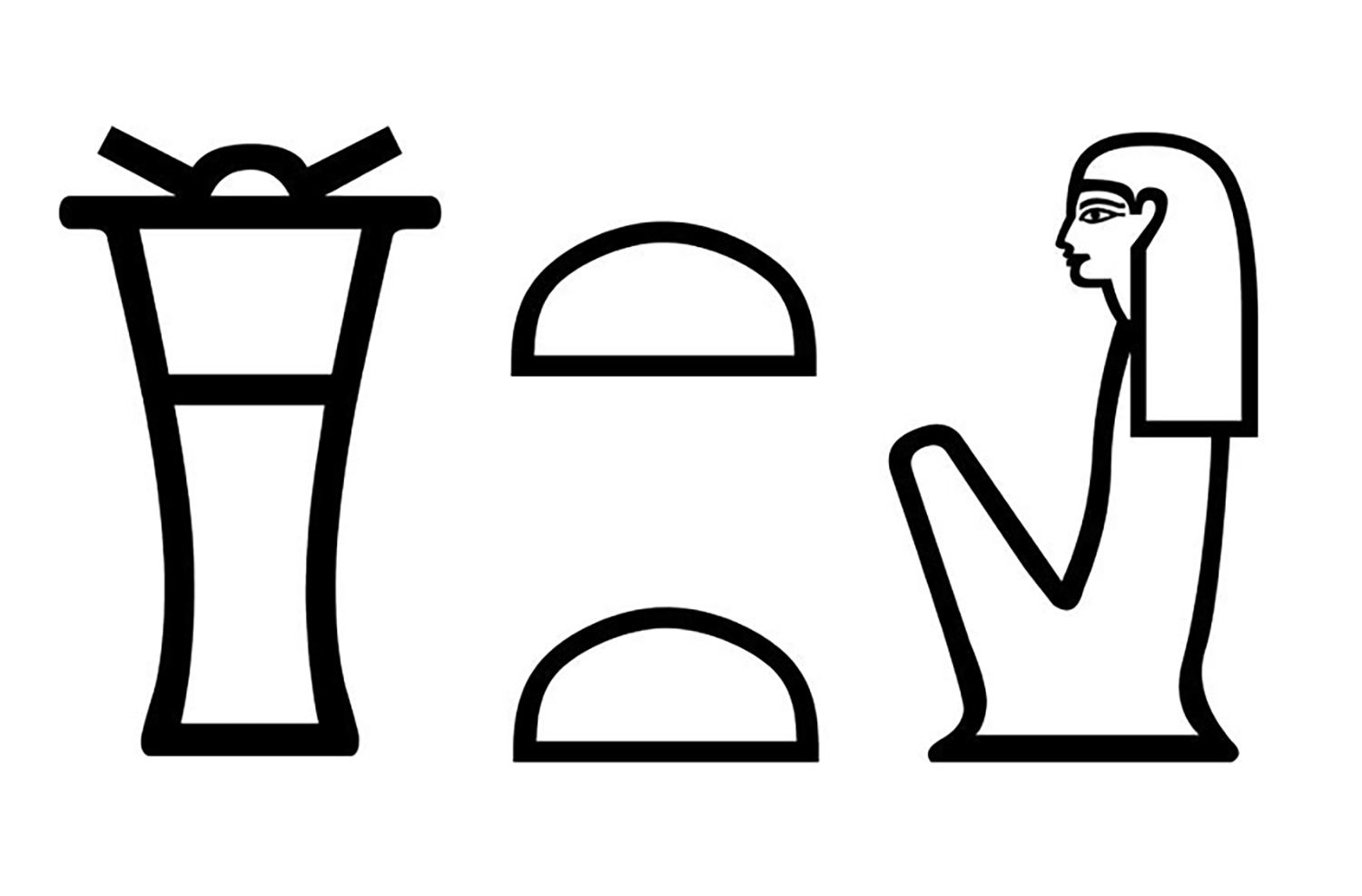

Firstly, one might ask, what was the word for “cat” in ancient Egypt? The word for cat was miu or miut (Figures 4 and 5), which probably sounded a lot like the sound a cat makes! (Interestingly, other ancient Egyptian animal names were also onomatopoeic, like the word iwiw for “dog,” which may have sounded like a dog’s bark.) Initially, humans in the Nile Valley probably appreciated the presence of cats near their homes because of the cats’ ability to control pest populations (Figure 6). Over time, as cats have done for thousands of years, these animals became beloved (and often pampered) pets. Depictions on tomb walls and on funerary stelae show domesticated cats seated under or near their owner’s chairs, and some pet cats were even afforded special burials with elaborately carved sarcophagi inscribed with the animal’s personal name. The best known of these pet cat coffins belonged to a royal pet, the cat Ta-miu (whose name means “The female cat”). Even Egyptian royalty loved cats!

Figure 4: Hieroglyphs for the word “cat,” reading miu.

Figure 5: Hieroglyphs for the word “cat,” reading miut.

Figure 6: A detail of a hunting cat from the tomb of Nebamun, Dynasty 18 (ca. 1350 BCE). British Museum EA37977. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

Feline and leonine imagery abounds in ancient Egypt, so it is clear that the Egyptians held cats in high esteem. Classical writers also observed the importance of the cat in Egyptian society and remarked on the ways in which cats seemed to be favored. The Greek historian Herodotus (who lived ca. c. 484–425 BCE) wrote much about his impressions of ancient Egyptian history, culture and religion. He too remarked on the special position of the cat in Egyptian society. He notes:

“Moreover when a fire occurs, the cats seem to be divinely possessed; for while the Egyptians stand at intervals and look after the cats, not taking any care to extinguish the fire, the cats slipping through or leaping over the men, jump into the fire; and when this happens, great mourning comes upon the Egyptians. And in whatever houses a cat has died by a natural death, all those who dwell in this house shave their eyebrows only, but those in whose houses a dog has died shave their whole body and also their head” (Herodotus, Histories 2.66).

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, who was active ca. 60 and 30 BCE, had much to say about the Egyptians’ relationship with cats. He recorded his personal observations of the fate of a person who harmed a cat in ancient Egypt:

“And whoever intentionally kills one of these animals is put to death, unless it be a cat or an ibis that he kills; but if he kills one of these, whether intentionally or unintentionally, he is certainly put to death, for the common people gather in crowds and deal with the perpetrator most cruelly, sometimes doing this without waiting for a trial. . . . So deeply implanted also in the hearts of the common people is their superstitious regard for these animals and so unalterable are the emotions cherished by every man regarding the honor due to them that once, at the time when Ptolemy their king had not as yet been given by the Romans the appellation of ‘friend’ and the people were exercising all zeal in courting the favor of the embassy from Italy which was then visiting Egypt and, in their fear, were intent upon giving no cause for complaint or war, when one of the Romans killed a cat and the multitude rushed in a crowd to his house, neither the officials sent by the king to beg the man off nor the fear of Rome which all the people felt were enough to save the man from punishment, even though his act had been an accident. And this incident we relate, not from hearsay, but we saw it with our own eyes on the occasion of the visit we made to Egypt” (Diodorus Siculus, Library of History I, 83.1-8).

The Macedonian author Polyaenus, who wrote in the 2nd-century CE, described a battle between the Egyptian army and that of the Persian king, Cambyses. He notes how the foreign invader used the Egyptians’ love of cats against them (Figure 7). He wrote:

“When Cambyses attacked Pelusium, which guarded the entrance into Egypt, the Egyptians defended it with great resolution. They advanced formidable engines against the besiegers, and hurled missiles, stones, and fire at them from their catapults. To counter this destructive barrage, Cambyses ranged before his front line dogs, sheep, cats, ibises, and whatever other animals the Egyptians hold sacred. The Egyptians immediately stopped their operations, out of fear of hurting the animals, which they hold in great veneration. Cambyses captured Pelusium, and thereby opened up for himself the route into Egypt” (Polyaenus, Stratagems in War 7:9).

Figure 7: An artist’s rendition of the battle of Pelusium showing Cambyses hurling cats at the city walls. Painted by Paul Marie Lenoir (French, 1843-1881). Cambyses at Pelusium – King Cambyse at the Siege of Peluse [1872], oil on canvas, exhibited at Paris Salon 1873.

The best known of all of the feline deities is the goddess Bastet. The meaning of her name is uncertain, but may mean something like “She of the ointment jar” (Figure 8). She was thought to be a daughter of the sun god, Re. Her religious center was at the city of Bubastis (Tell Basta) in the Delta. We can see an example of royal interaction with a divine feline on Glencairn’s stela (Figure 9), dated to the reign of the Saite King Psammetichus II (reigned ca. 595 BCE–589 BCE). Interestingly, on this stela we also get a chance to meet Bastet’s son, a god named Hor-hekenu. The stela depicts the king before this pair of deities. He offers them a wedjat eye. Bastet, shown as a woman with a cat head, stands in front and her falcon-headed son stands behind. The text identifies her as “Bastet, the great, Mistress of Bubastis.” Herodotus (writing in the 5th-century BCE) described a festival that took place at Bubastis as follows:

“Men and women come sailing all together, vast numbers in each boat, many of the women with castanets, which they strike, while some of the men pipe during the whole time of the voyage; the remainder of the voyagers, male and female, sing the while, and make a clapping with their hands. When they arrive opposite any of the towns upon the banks of the stream, they approach the shore, and, while some of the women continue to play and sing, others call aloud to the females of the place and load them with abuse, while a certain number dance, and some standing up uncover themselves. After proceeding in this way all along the river-course, they reach Bubastis, where they celebrate the feast with abundant sacrifices. More grape-wine is consumed at this festival than in all the rest of the year besides. The number of those who attend, counting only the men and women and omitting the children, amounts, according to the native reports, to seven hundred thousand” (Herodotus, Histories 2.60).

Figure 8: The name of Bastet in hieroglyphs.

Figure 9: A stela dated to the reign of King Psammetichus II showing the king offering before Bastet and her son. Glencairn Museum E1152.

Bastet appears in the written record as early as the Second Dynasty (ca. 2800-2675 BCE). Texts make it clear from the start that she has a gentle and protective nature. In the Pyramid Texts of the Old Kingdom she is described as the deceased king’s nurse, and in the Middle Kingdom Coffin Texts she protects the deceased. At first her iconography is that of a cat. By the time of the New Kingdom she appears as a woman with a cat’s head.

Bastet’s place was in the home. She was primarily a protective domestic goddess who, like a mother cat with her kittens, took good care of the children in the house. As a goddess closely connected to motherhood, fertility and nurturing, a popular way in which Bastet is shown is as a mother cat nursing her litter. Glencairn houses a charming bronze votive statuette of a mother cat suckling several kittens (Figure 10). Dating to the Late Period, this cat undoubtedly would call to mind the protective nature of the goddess Bastet in her role as a domestic goddess taking care of the family, house and home. It may also express a wish for fertility. Just as the mother cat has her litter of kittens, perhaps the dedicator also wished to have a large family!

Figure 10: A bronze votive statuette of a nursing cat and her litter, Late Period (664-332 BCE). Glencairn Museum E971.

Many depictions of female deities and royal women show them holding a sistrum. A sistrum is a musical instrument that was shaken like a rattle. This instrument was a part of many cult rituals and the sistrum is closely connected to the worship of several Egyptian goddesses. A wonderful detail on the top of the sistrum in Glencairn’s collection is the depiction of another mother cat nursing her kittens (Figure 11). The imagery is almost identical to that of Glencairn’s small bronze votive of the mother cat with her kittens, and again highlights a wish for fertility and protection.

Figure 11: A bronze sistrum, Late Period (664-332 BCE). A detail (right) from the top of the sistrum depicting a mother cat and her kittens. Glencairn Museum E1269.

Another type of votive we find in Glencairn’s collection is also related to fertility and felines. The collection includes a small limestone figure of a sleeping woman (Figure 12). A pair of seated felines decorates the footboard of her bed. Votives of this type clearly are connected to fertility and rebirth. These figurines may have been displayed in household shrines or dedicated at temples. The cat imagery offers protection to the sleeping woman and, just as the imagery of the mother cat with her kittens that we see on the small bronze votive and the sistrum may have expressed a wish for fertility and a large family, so too the cats on the footboard may have communicated this same desire.

Figure 12: A limestone statuette of a woman on a bed with cat iconography on the footboard, New Kingdom–Late Period (1539-332 BCE). Glencairn Museum E1219.

Bastet was tremendously popular and many images and amulets of her were produced, to be worn by worshippers as amulets, or dedicated at temples as offerings. Small votive figurines of the goddess Bastet are well known from the Late Period (ca. 664-332 BCE). In many of these votives, Bastet is shown with a feline head and a human body (Figure 13). She wears a long tight-fitting dress, and holds an aegis in her hand. An aegis was a cult object that usually shows the head of a female deity atop a large broad collar. The aegis had protective power and was often placed on temple equipment. Female deities can also be shown holding an aegis in their hands. From her arm, a situla hangs. A situla is a container used to hold liquid for religious ceremonies. Her other hand is broken away, but it is likely that she originally held a sistrum, very much like the complete example in Glencairn’s collection.

Figure 13: Bronze votive of a standing Bastet, Late Period (664-332 BCE). Glencairn Museum E969.

Pilgrims visiting Egyptian temples could dedicate small bronze statuettes of cats—perhaps representing Bastet (or another of the feline deities)—to this goddess with the hope that the deity would answer their prayers or to thank a deity for prayers answered. Perhaps the best known of these cat votive statues is the example in the British Museum. Known as the Gayer-Anderson cat, this statue is a masterpiece of feline elegance (Figure 14). The cat wears a golden earring and a gold hoop nose ring. The Penn Museum in Philadelphia also has a bronze cat statue (Figure 15). It is not nearly as elegant as the example in the British Museum, but like the British Museum’s cat, the statue is hollow cast bronze. Close inspection of the Penn Museum’s example revealed a dedicatory inscription on the cat’s rump and it has been suggested that this hollow statue may have served as a vessel for a cat mummy.

Figure 14: The bronze hollow-cast Gayer-Anderson cat figure with details in silver and gold, Late Period (664-332 BCE). British Museum EA64391. Image courstesy of the British Museum.

Figure 15: Bronze cat with gilded details, Dynasty 22 or later (945-712 BCE or later). Penn Museum E14284.

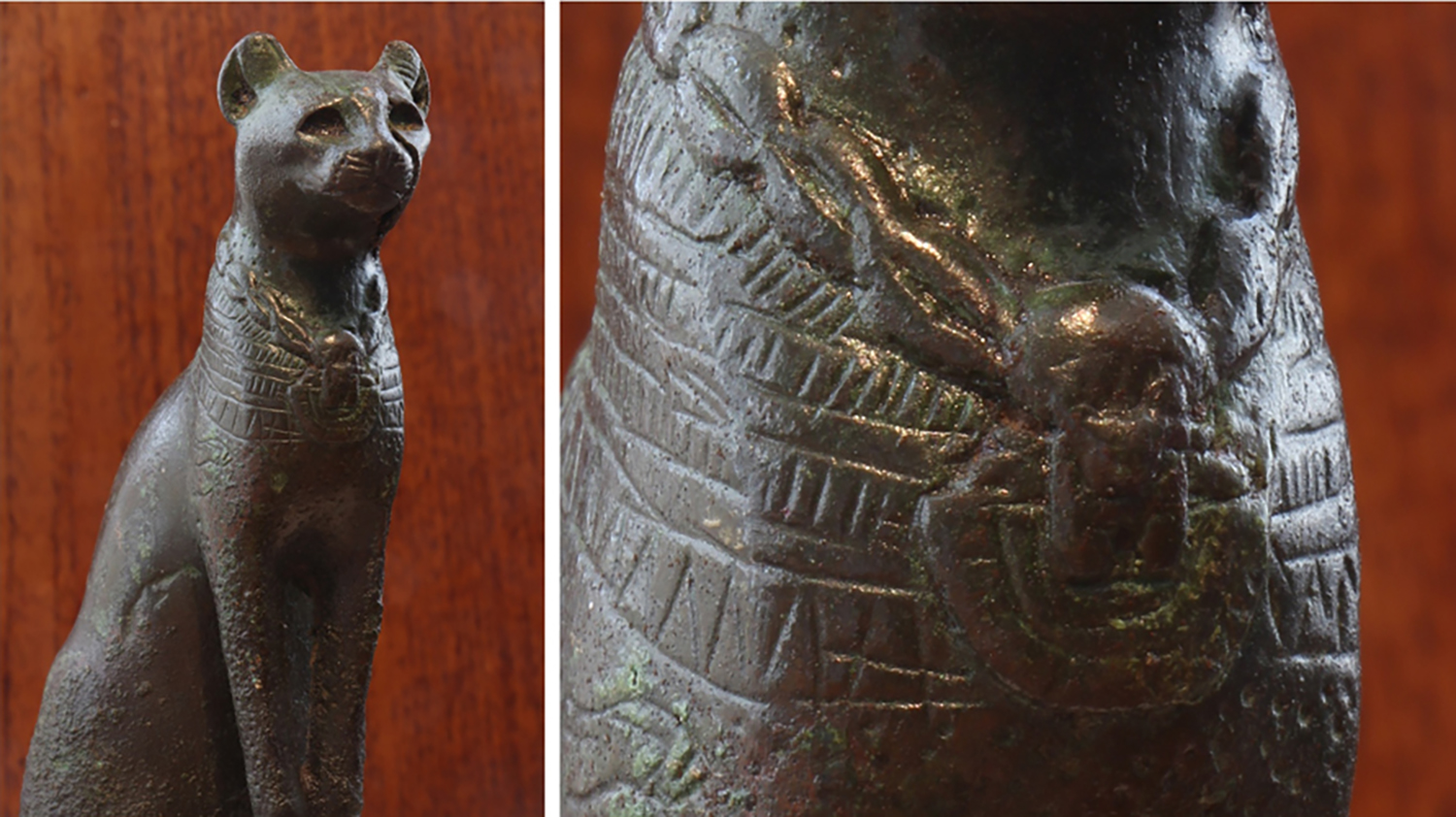

Glencairn Museum also has a bronze votive in the form of a seated cat (Figure 16). The cat wears an elaborate necklace that features an aegis pendant. In this case, the aegis worn by the cat is topped with the head of a feline, likely the goddess Bastet. An example of a gold pendant with this same form can be seen in the Penn Museum (Figure 17). This is the exact same imagery we see on the small standing Bastet votive figure in the Glencairn collection. Other protective imagery, such as the wedjat eye, also decorates the statue. Like the Penn Museum’s cat statue, it is also likely that this votive contained a cat mummy. The hollow statue still contains feline bones, perhaps originally from a mummified cat (Figure 18).

Figure 16: Seated bronze cat votive, Late Period (664-332 BCE). Detail of the aegis pectoral on the chest of the cat (right). Glencairn Museum E60.

Figure 17: Gold amulet of an aegis with a leonine head from Meydum, Egypt, Late Period (664-332 BCE). Penn Museum 31-27-272.

Figure 18: The interior of Glencairn’s bronze cat votive contains feline bones, perhaps from a mummified cat. Glencairn Museum E60.

Many museum collections around the world house cat mummies. More often than not, these cat mummies were originally votive offerings dedicated by worshippers at temples dedicated to Bastet, or another feline deity. Literally thousands upon thousands of cat mummies have been excavated in Egypt. These cats were not beloved pets, but were raised to become votive offerings (Figure 19).

Figure 19: Cat mummy with modeled head and linen wrappings, Roman Period (post 30 BCE). British Museum EA6758. Image courtesy of the British Museum.

What about the lion? How does the lion fit into the Egyptian pantheon? The ancient Egyptians—like many ancient and modern peoples—were fascinated by the strength, power, and majesty of the lion. As early as the Predynastic period, leonine imagery was important in Egyptian art (Figure 20). Buried lions have been excavated in connection with royal tombs at Hierakonpolis and Abydos. Numerous deities including Sekhmet, Mut, Mehyt, Pakhet, Tefnut and Mahes all can appear in leonine form. The best known of these is Sekhmet. At Memphis, Sekhmet was the wife and consort of the god Ptah. However, she is a deity with a complex identity and a major role in Egyptian religion. Like Bastet, Sekhmet, whose name means “The-powerful-female-one,” was thought to be a daughter of the sun god (Figure 21). She is often portrayed as a fearsome deity with warlike tendencies. Sekhmet was thought to accompany the king into battle (Figure 22). Although Sekhmet could rage at her enemies, she was also a nurturing deity. One of her roles was that of divine guardian who could ward off illnesses; in particular, a disease called the “plague of the year.”

Figure 20: Ivory game piece in the form of a lion from Abydos, Egypt, Dynasty 1 (3000-2800 BCE). Penn Museum E11522.

Figure 21: The name of Sekhmet in hieroglyphs.

Figure 22: Limestone relief depicting Merneptah attacking enemies accompanied by a lioness, from the palace of Merenptah at Memphis, Dynasty 19 (1213-1204 BCE). Penn Museum E17527.

We’ve seen a lot of cats at Glencairn, but there are some lions here too! During the reign of Amenhotep III (reigned ca. 1391 BCE–1353 BCE), hundreds of statues of the goddess Sekhmet, like the Glencairn example (Figure 23), were erected in Theban temples to serve a protective function. Many of these statues were set up near the precinct of the goddess Mut at Karnak. The goddesses Mut and Sekhmet are closely associated. Mut, like Sekhmet, could take a leonine form. Sekhmet was considered a northern goddess, and Mut was her southern equivalent. Here, Sekhmet has the ruff typical of a lioness. Her body would have been in the form of a human female. Her sun disk with a rearing uraeus (cobra) illustrates her connection to her father, the sun god Re. In Egyptian mythology, Sekhmet represents the “Eye” of the sun and can act on behalf of the sun god. It is also possible that these many statues (including the Glencairn example) were erected with the hope that they would ward off an actual plague that was afflicting the Theban area during the reign of Amenhotep III.

Figure 23: Head from a granite statue of the goddess Sekhmet, New Kingdom (ca. 1391 BCE–1353 BCE). Glencairn Museum E1157.

Finally, we can consider the many feline amulets in Glencairn’s collection (Figure 24). Amulets were worn by the living and were buried with the dead. Amulets could be made of a variety of materials such as stone, faience or precious metals. Images of feline and leonine deities were popular. Representations of cats or cat-headed goddesses were likely connected to Bastet, who was revered as a goddess of fertility and protector of the home. Sometimes Bastet is shown alone, other times she is depicted in the company of many kittens (as we have seen on the votive and sistrum in the Glencairn collection). Perhaps amulets of Bastet as a mother cat were worn by women who hoped to share in this fecundity. Amulets of leonine goddesses may represent Sekhmet, Mut, or less commonly, the goddess Pakhet. These amulets offered protection to their wearer.

Figure 24: An assortment of feline and leonine amulets in the Glencairn collection.

Much of the ancient Egyptian world was understood in terms of complementary opposites, perhaps in response to the natural world around them—the fertile Nile Valley and the dry desolate desert. Similarly, some ancient Egyptian goddesses had this dual nature. Perhaps the best example would be our goddesses Sekhmet and Bastet (Figure 25). Sekhmet’s peaceful counterpart was Bastet. While both of these goddesses were feline in nature, they were opposite in activity and action. The ancient Egyptian myth of the Eye of the Sun makes the literary allusion when describing the goddess Hathor-Tefnut: “She rages like Sekhmet and is friendly like Bastet.” Again, we can turn to the Demotic wisdom literature for an illustration of this duality. We find in Onchsheshonqy these lines: “A man who smells of myrrh, his wife is a cat in his presence. A man who is in distress, his wife is a lioness in his presence” (Onchsheshonqy 15/11-12).

Figure 25: A faience amulet of Sekhmet, post Third Intermediate Period (after 656 BCE) and a bronze votive statuette of Bastet, Late Period (664-332 BCE). Penn Museum E14357 and 29-70-695.

Figure 26: A very content Abydos dig house cat.

Jennifer Houser Wegner, PhD

Associate Curator, Egyptian Section

Penn Museum

Select Bibliography

Andrews, Carol 1994. Amulets of ancient Egypt. London: The British Museum Press.

De Jong, Aleid 2001. Feline Deities. In D. Redford (ed.) The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press.

Lesko, Barbara S. 1999. The great goddesses of Egypt. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Malek, Jaromir 2006. The cat in ancient Egypt, Revised ed. London: British Museum Press.

Silverman, David P. (ed.) 1997. Searching for ancient Egypt: art, architecture, and artifacts from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press.

Simpson, William Kelly (ed.) 2003. The literature of ancient Egypt: an anthology of stories, instructions, stelae, autobiographies, and poetry, third ed. New Haven; London: Yale University Press.

Stück, L. 1976. Katz. In Lexikon der Ägyptologie, 3: 367–370. Wiesbaden.

Wilkinson, Richard H. 2003. The complete gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson.

A complete archive of past issues of Glencairn Museum News is available online here.

![Figure 7: An artist’s rendition of the battle of Pelusium showing Cambyses hurling cats at the city walls. Painted by Paul Marie Lenoir (French, 1843-1881). Cambyses at Pelusium – King Cambyse at the Siege of Peluse [1872], oil on canvas, exhibited …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56829c58a2bab87f93ee4d6a/1529345394514-MPQASEHQPBJ62YBQOAYQ/image-asset.jpeg)